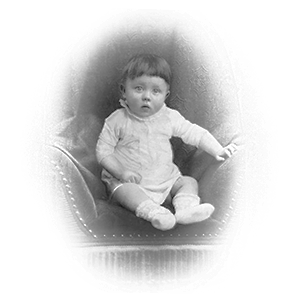

Killing baby Hitler is a thought experiment in ethics and theoretical physics which poses the question of using time travel to assassinate an infant Adolf Hitler. It presents an ethical dilemma in both the action and its consequences, as well as a temporal paradox in the logical consistency of time. Killing baby Hitler first became a literary trope of science fiction during World War II and has since been used to explore these ethical and metaphysical debates.

Public debate around the question of killing baby Hitler reached its height in late 2015, after ‘The New York Times’ published a poll asking its readers the question. 42% said they would kill baby Hitler, 30% said they would not and 28% were undecided. Advocates of killing baby Hitler included Florida governor Jeb Bush and film actor Tom Hanks, while comedian Stephen Colbert and pundit Ben Shapiro were counted among the opponents of the policy.

Metaphysical debates about the possibility of killing baby Hitler have been used to discuss different philosophies of time. The ‘B-theory of time’ posits that all points in time—past, present, and future—are equally real, viewing the flow of time as a subjective illusion and denying any special ontological status to the present. The B-theory of time considers killing baby Hitler to be impossible due to its inherent temporal paradox, while theories of multiple time dimensions leave room for the past to be changed by killing baby Hitler.

Ethical debates on the problem of killing baby Hitler can demonstrate the outlook of various moral philosophies. Utilitarianism, the doctrine that actions are right if they are useful or for the benefit of a majority, holds that killing baby Hitler is justified, as the potential benefits outweigh the potential costs. Deontology, an ethical theory that uses rules to distinguish right from wrong, holds that killing baby Hitler is unjustified, as infanticide is always wrong.

Consequentialism, an ethical theory that judges the rightness or wrongness of an action based on its consequences, questions what the consequences of killing baby Hitler might be, holding that the unforeseen future consequences of such an act make it difficult to judge its morality. It is also used to raise the question of nature versus nurture, whether changing the society that baby Hitler grew up in might be preferable to killing baby Hitler.

The moral justification for killing baby Hitler usually rests on the question of whether a child can be held responsible for their future actions, before they had yet committed any crimes against humanity. A follow-up question can then be posed regarding where the line ends for killing babies that would commit crimes against humanity. The question of where the line ends was brought up by American activist Shaun King, who argued that the logic for killing baby Hitler could just as easily be applied to a newborn Christopher Columbus, infant slave-owners or a young Dylann Roof.

The question of killing baby Hitler contains a version of the grandfather paradox, also known as the ‘Hitler’s Murder Paradox.’ According to the B-theory of time, if someone travelled back in time with the intention of killing baby Hitler, then their reason for travelling back in time would be eliminated. It is often concluded that as the past has already happened, alteration of the past is a logical impossibility. As Hitler killed himself in 1945, it can also be inferred that no time traveler has killed baby Hitler.

In contrast to the B-theory, models that adopt the A-theory of time (the view that the passage of time is an objective feature of reality, and that the present moment is metaphysically privileged) avoid logical contradictions in the killing of baby Hitler by considering time to be two-dimensional, where the first dimension is standard time and the second dimension is known as hyper-time. Theories that leave room for the past to be changed include hyper-eternalism, two-dimensional presentism and hyper-presentism, which each demonstrate the possibility of killing baby Hitler in two-dimensional time. In these temporal models, both the past and the future are held to be mutable; in changing the past by killing baby Hitler, the time traveller also changes the future. Although it can also be debated whether such temporal models genuinely change the past, or if killing baby Hitler simply affects the past by causing a variation in hyper-time.

If time travel caused creation of a parallel universe, killing baby Hitler would only create a parallel universe without Hitler in it, and the original universe would continue existing and thus the suffering he caused in that timeline would not be alleviated by the time-traveling assassin. From this perspective, astrophysicist Brian Koberlein concluded that killing baby Hitler would be ‘inconsequential at best, and could be downright harmful,’ recommending that time travelers avoid such an activity and instead visit the 1980s.

Killing baby Hitler is a common literary trope of contemporary science fiction, usually depicting a time traveler going back to the 1890s to assassinate an infant Hitler before he can start World War II and perpetrate the Holocaust. Stories of this kind date as far back as World War II itself, with publications in ‘Weird Tales’ (1941) and ‘Astounding Science Fiction’ (1942) including the trope. In order to avoid the ‘Hitler-murder paradox,’ some science fiction stories follow the Novikov self-consistency principle, which holds that if time travel is possible, then changing the past cannot meaningfully alter the future. An episode of ‘The Twilight Zone,’ ‘No Time Like the Past’ (1963), depicts a time traveler failing to assassinate Hitler, in keeping with the self-consistency principle.

In conversations about time travel, it is common to raise the subject of changing the past and specifically the question of killing baby Hitler, in what is also known as ‘Godwin’s law of time travel, which states: ‘As the amount of time-traveling you do increases, the probability of Hitler winning World War II approaches 1.’

The Daily Omnivore

Everything is Interesting

Leave a comment