The Buffett Indicator, named after Warren Buffett, measures market valuation by dividing a country’s total stock market value by its GDP. A ratio of 100% suggests fair market. For example, if stocks are worth $50 trillion and GDP is $25 trillion, a 200% ratio would suggest the market is overvalued.

It was proposed as a metric by Buffett in 2001, who called it ‘probably the best single measure of where valuations stand at any given moment,’ and its modern form compares the capitalization of the US Wilshire 5000 index to US GDP. It is widely followed by the financial media as a valuation measure for the US market in both its absolute, and de-trended forms. The indicator set an all-time high during the so-called ‘everything bubble,’ crossing the 200% level in February 2021; a level that Buffett warned if crossed, was ‘playing with fire.’

In December 2001, Buffett proposed the metric in a ‘Fortune’ essay co-authored with journalist Carol Loomis. In the essay, Buffett presented a chart going back 80 years that showed the value of all ‘publicly traded securities’ in the U.S. as a percentage of ‘U.S. GNP.’ Buffett explained that for the annual return of U.S. securities to materially exceed the annual growth of U.S. GNP for a protracted period of time: ‘you need to have the line go straight off the top of the chart. That won’t happen.’ Buffett finished the essay by outlining the levels he believed the metric showed favorable or poor times to invest: ‘For me, the message of that chart is this: If the percentage relationship falls to the 70% or 80% area, buying stocks is likely to work very well for you. If the ratio approaches 200%–as it did in 1999 and a part of 2000–you are playing with fire.’

A study by two European academics published in May 2022 found the Buffett Indicator ‘explains a large fraction of ten-year return variation for the majority of countries outside the United States.’ The study examined 10-year periods in fourteen developed markets, in most cases with data starting in 1973. The Buffett Indicator forecasted an average of 83% of returns across all nations and periods, though the predictive value ranged from a low of 42% to as high as 93% depending on the specific nation. Accuracy was lower in nations with smaller stock markets.

Buffett acknowledged that his metric was a simple one and thus had ‘limitations,’ however the underlying theoretical basis for the indicator, particularly in the U.S., is considered reasonable. For example, studies have shown a consistent and strong annual correlation between U.S. GDP growth, and U.S. corporate profit growth, and which has increased materially since the Great Recession of 2007–2009. GDP captures effects where a given industry’s margins increase materially for a period, but the effect of reduced wages and costs, dampening margins in other industries.

The same studies show a poor annual correlation between U.S. GDP growth and US equity returns, underlining Buffett’s belief that when equity prices get ahead of corporate profits (via the GNP/GDP proxy), poor returns will follow. The indicator has also been advocated for its ability to reduce the effects of ‘aggressive accounting’ or ‘adjusted profits,’ that distort the value of corporate profits in the price–earnings ratio or EV/EBITDA ratio metrics; and that it is not affected by share buybacks (which don’t affect aggregate corporate profits).

The Buffett indicator has been calculated for most international stock markets, however, caveats apply as other markets can have less stable compositions of listed corporations (e.g. the Saudi Arabia metric was materially impacted by the 2018 listing of Aramco), or a significantly higher/lower composition of private vs public firms (e.g. Germany vs. Switzerland), and therefore comparisons across international markets using the indicator as a comparative measure of valuation are not appropriate.

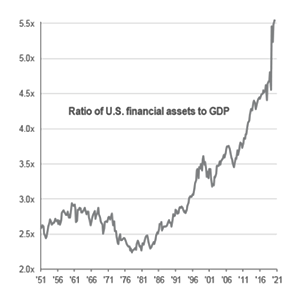

There is evidence that the Buffett indicator has trended upwards over time, particularly post 1995, and the lows registered in 2009 would have registered as average readings from the 1950–1995 era. Reasons proposed include that GDP might not capture all the overseas profits of US multinationals (e.g. use of tax havens or tax structures by large U.S. technology and life sciences multinationals), or that the profitability of U.S. companies has structurally increased (e.g. due to increased concentration of technology companies), thus justifying a higher ratio; although that may also revert over time. Other commentators have highlighted that the omission by metric of corporate debt, could also be having an effect.

The choice of how GDP is calculated (e.g. deflator), can materially affect the absolute value of the ratio; for example, the Buffett indicator calculated by the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis peaks at 118% in Q1 2000, while the version calculated by Wilshire Associates peaks at 137% in Q1 2000, while the versions following Buffett’s original technique, peak at very close to 160% in Q1 2000.

The Daily Omnivore

Everything is Interesting

Leave a comment