In quantum computing, quantum supremacy or quantum advantage is the goal of demonstrating that a programmable quantum computer can solve a problem that no classical computer can solve in any feasible amount of time, irrespective of the usefulness of the problem. The term was coined by Caltech theoretical physicist John Preskill in 2011, but the concept dates to Russian mathematician Yuri Manin’s 1980 and theoretical physicist Richard Feynman’s 1981 proposals of quantum computing.

Conceptually, quantum supremacy involves both the engineering task of building a powerful quantum computer and the computational-complexity-theoretic task of finding a problem that can be solved by that quantum computer and has a superpolynomial speedup over the best known or possible classical algorithm for that task.

A notable property of quantum supremacy is that it can be feasibly achieved by near-term quantum computers, since it does not require a quantum computer to perform any useful task or use high-quality quantum error correction, both of which are long-term goals. Consequently, researchers view quantum supremacy as primarily a scientific goal, with relatively little immediate bearing on the future commercial viability of quantum computing. Due to unpredictable possible improvements in classical computers and algorithms, quantum supremacy may be temporary or unstable, placing possible achievements under significant scrutiny.

In 1936, Alan Turing published his paper, ‘On Computable Numbers,’ in response to the 1900 Hilbert Problems. Turing’s paper described what he called a ‘universal computing machine,’ which later became known as a Turing machine. In 1980, Paul Benioff used Turing’s paper to propose the theoretical feasibility of Quantum Computing. His paper, ‘The Computer as a Physical System: A Microscopic Quantum Mechanical Hamiltonian Model of Computers as Represented by Turing Machines,’ was the first to demonstrate that it is possible to show the reversible nature of quantum computing as long as the energy dissipated is arbitrarily small. In 1981, Richard Feynman showed that quantum mechanics could not be efficiently simulated on classical devices. During a lecture, he delivered the famous quote, ‘Nature isn’t classical, dammit, and if you want to make a simulation of nature, you’d better make it quantum mechanical, and by golly it’s a wonderful problem, because it doesn’t look so easy.’ Soon after this, Oxford physicist David Deutsch produced a description for a quantum Turing machine and designed an algorithm created to run on a quantum computer.

In 1994, further progress toward quantum supremacy was made when Peter Shor formulated Shor’s algorithm, streamlining a method for factoring integers in polynomial time. In 1995, Christopher Monroe and David Wineland published their paper, ‘Demonstration of a Fundamental Quantum Logic Gate,’ marking the first demonstration of a quantum logic gate, specifically the two-bit ‘controlled-NOT.’ Vast progress toward quantum supremacy was made in the 2000s from the first 5-qubit nuclear magnetic resonance computer (2000), the demonstration of Shor’s theorem (2001), and the implementation of Deutsch’s algorithm in a clustered quantum computer (2007). In 2011, D-Wave Systems of Burnaby, British Columbia, Canada became the first company to sell a quantum computer commercially. In 2012, physicist Nanyang Xu landed a milestone accomplishment by using an improved adiabatic factoring algorithm to factor 143. However, the methods used by Xu were met with objections. Not long after this accomplishment, Google purchased its first quantum computer.

In December 2020, a group based in the University of Science and Technology of China (USTC) led by Pan Jianwei reached quantum supremacy by implementing gaussian boson sampling on 76 photons with their photonic quantum computer Jiuzhang. The paper states that to generate the number of samples the quantum computer generates in 200 seconds, a classical supercomputer would require 2.5 billion years of computation.

In October 2021, teams from USTC again reported quantum primacy by building two supercomputers called Jiuzhang 2.0 and Zuchongzhi. The light-based Jiuzhang 2.0 implemented gaussian boson sampling to detect 113 photons from a 144-mode optical interferometer and a sampling rate speed up of 1024 – a difference of 37 photons and 10 orders of magnitude over the previous Jiuzhang. Zuchongzhi is a programmable superconducting quantum computer that needs to be kept at extremely low temperatures to work efficiently and uses random circuit sampling to obtain 56 qubits from a tunable coupling architecture of 66 transmons—an improvement over Google’s Sycamore 2019 achievement by 3 qubits, meaning a greater computational cost of classical simulation of 2 to 3 orders of magnitude.

In March of 2024, D-Wave Systems reported on an experiment using a quantum annealing based processor that out-performed classical methods including tensor networks and neural networks. They argued that no known classical approach could yield the same results as the quantum simulation within a reasonable time-frame and claimed quantum supremacy. The task performed was the simulation of the non-equilibrium dynamics of a magnetic spin system quenched through a quantum phase transition.

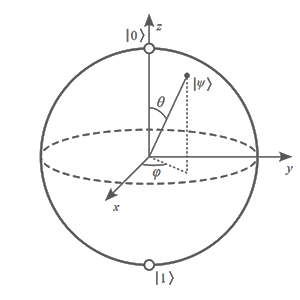

A circuit model and its corresponding operations are useful in describing both classical and quantum problems; the classical circuit model consists of basic operations such as AND gates, OR gates, and NOT gates while the quantum model consists of classical circuits and the application of unitary operations. Unlike the finite set of classical gates, there are an infinite amount of quantum gates due to the continuous nature of unitary operations. In both classical and quantum cases, complexity swells with increasing problem size. The difficulty of proving what cannot be done with classical computing is a common problem in definitively demonstrating quantum supremacy. Contrary to decision problems that require yes or no answers, sampling problems ask for samples from probability distributions.

Quantum computers are much more susceptible to errors than classical computers due to decoherence and noise. The threshold theorem states that a noisy quantum computer can use quantum error-correcting codes to simulate a noiseless quantum computer, assuming the error introduced in each computer cycle is less than some number. Numerical simulations suggest that that number may be as high as 3%. However, it is not yet definitively known how the resources needed for error correction will scale with the number of qubits. Skeptics point to the unknown behavior of noise in scaled-up quantum systems as a potential roadblock for successfully implementing quantum computing and demonstrating quantum supremacy.

Some researchers have suggested that the term ‘quantum supremacy’ should not be used, arguing that the word ‘supremacy’ evokes distasteful comparisons to the racist belief of white supremacy. A controversial commentary article in the journal ‘Nature’ signed by thirteen researchers asserts that the alternative phrase ‘quantum advantage’ should be used instead. John Preskill, the professor of theoretical physics at the California Institute of Technology who coined the term, has since clarified that the term was proposed to explicitly describe the moment that a quantum computer gains the ability to perform a task that a classical computer never could. He further explained that he specifically rejected the term ‘quantum advantage’ as it did not fully encapsulate the meaning of his new term: the word ‘advantage’ would imply that a computer with quantum supremacy would have a slight edge over a classical computer while the word ‘supremacy’ better conveys complete ascendancy over any classical computer.

The Daily Omnivore

Everything is Interesting

Leave a comment