AlphaGo versus Lee Sedol, also known as the DeepMind Challenge Match, was a five-game Go match between top Go player Lee Sedol and AlphaGo, a computer Go program developed by DeepMind, played in Seoul, South Korea between 9 and 15 March 2016. AlphaGo won all but the fourth game; all games were won by resignation. The match has been compared with the historic chess match between Deep Blue and Garry Kasparov in 1997. Kasparov’s loss to Deep Blue is considered the moment a computer became better than humans at chess.

AlphaGo’s victory was a major milestone in artificial intelligence research. Most experts thought a Go program as powerful as AlphaGo was at least five years away; some experts thought that it would take at least another decade before computers would beat Go champions. Most observers at the beginning of the 2016 matches expected Lee to beat AlphaGo. With games such as checkers, chess, and now Go won by computer players, victories at popular board games can no longer serve as significant milestones for artificial intelligence in the way that they used to. Deep Blue’s Murray Campbell called AlphaGo’s victory ‘the end of an era… board games are more or less done and it’s time to move on.’

After the match, The Korea Baduk Association awarded AlphaGo the highest Go grandmaster rank – an ‘honorary 9 dan.’ It was given in recognition of AlphaGo’s ‘sincere efforts’ to master Go. This match was chosen by ‘Science’ as one of the runners-up for Breakthrough of the Year, on 22 December 2016.

Go is a complex board game that requires intuition, creative and strategic thinking. It has long been considered a difficult challenge in the field of artificial intelligence (AI). It is considerably more difficult to solve than chess. Many in artificial intelligence consider Go to require more elements that mimic human thought than chess. Mathematician I. J. Good wrote in 1965: ‘Go on a computer? – In order to program a computer to play a reasonable game of Go, rather than merely a legal game – it is necessary to formalise the principles of good strategy, or to design a learning program. The principles are more qualitative and mysterious than in chess, and depend more on judgement. So, I think it will be even more difficult to program a computer to play a reasonable game of Go than of chess.’

Prior to 2015, the best Go programs only managed to reach amateur dan level. On the small 9×9 board, the computer fared better, and some programs managed to win a fraction of their 9×9 games against professional players. Before AlphaGo, some researchers had claimed that computers would never defeat top humans at Go.

AlphaGo is significantly different from previous AI efforts. Instead of using probability algorithms hard-coded by human programmers, AlphaGo uses neural networks to estimate its probability of winning. AlphaGo accesses and analyses the entire online library of Go, including all matches, players, analytics, literature, and games played by AlphaGo against itself and other players. Once set up, AlphaGo is independent of the developer team and evaluates the best pathway to solving Go (i.e., winning the game). By using neural networks and Monte Carlo tree search, AlphaGo calculates colossal numbers of likely and unlikely probabilities many moves into the future. Related research results are being applied to fields such as cognitive science, pattern recognition and machine learning.

AlphaGo was initially trained to mimic human play by attempting to match the moves of expert players from recorded historical games, using a KGS Go Server database of around 30 million moves from 160,000 games by KGS 6 to 9 dan human players. Once it had reached a certain degree of proficiency, it was trained further by being set to play large numbers of games against other instances of itself, using reinforcement learning to improve its play. The system does not use a ‘database’ of moves to play. As one of the creators of AlphaGo explained: ‘Although we have programmed this machine to play, we have no idea what moves it will come up with. Its moves are an emergent phenomenon from the training. We just create the data sets and the training algorithms. But the moves it then comes up with are out of our hands—and much better than we, as Go players, could come up with.’ In the match against Lee, AlphaGo used 1,202 CPUs and 176 GPUs. Google has also stated that its proprietary tensor processing units were used in the match.

Lee Sedol is a professional Go player of 9 dan rank and is one of the strongest players in the history of Go. He started his career in 1996 (promoted to professional dan rank at the age of 12), winning 18 international titles since then. He is a ‘national hero’ in his native South Korea, known for his unconventional and creative play.

AlphaGo won the first game. Lee appeared to be in control throughout the match, but AlphaGo gained the advantage in the final 20 minutes, and Lee resigned. Lee stated afterwards that he had made a critical error at the beginning of the match; he said that the computer’s strategy in the early part of the game was ‘excellent’ and that the AI had made one unusual move that no human Go player would have made.

AlphaGo won the second game. Lee stated afterwards that ‘AlphaGo played a nearly perfect game,’ ‘from very beginning of the game I did not feel like there was a point that I was leading.’ One of the creators of AlphaGo, Demis Hassabis, said that the system was confident of victory from the midway point of the game, even though the professional commentators could not tell which player was ahead. Michael Redmond (9p) noted that AlphaGo’s 19th stone (move 37) was ‘creative’ and ‘unique.’ It was a move that no human would’ve ever made. Lee took an unusually long time to respond. An Younggil (8p) called AlphaGo’s move 37 ‘a rare and intriguing shoulder hit’ but said Lee’s counter was ‘exquisite.’ He stated that control passed between the players several times before the endgame.

AlphaGo showed anomalies and moves from a broader perspective, which professional Go players described as looking like mistakes at first sight but an intentional strategy in hindsight. As one of the creators of the system explained, AlphaGo does not attempt to maximize its points or its margin of victory, but tries to maximize its probability of winning. If AlphaGo must choose between a scenario where it will win by 20 points with 80 percent probability and another where it will win by 1 and a half points with 99 percent probability, it will choose the latter, even if it must give up points to achieve it. In particular, move 167 by AlphaGo seemed to give Lee a fighting chance and was declared to look like a blatant mistake by commentators. An Younggil said, ‘So when AlphaGo plays a slack looking move, we may regard it as a mistake, but perhaps it should more accurately be viewed as a declaration of victory?’

After the second game, players still had doubts about whether AlphaGo was truly a strong player in the sense that a human might be. The third game was described as removing that doubt, with analysts commenting that: ‘AlphaGo won so convincingly as to remove all doubt about its strength from the minds of experienced players. In fact, it played so well that it was almost scary … In forcing AlphaGo to withstand a very severe, one-sided attack, Lee revealed its hitherto undetected power … Lee wasn’t gaining enough profit from his attack … One of the greatest virtuosos of the middle game had just been upstaged in black and white clarity.’ According to An Younggil (8p) and David Ormerod, the game showed that ‘AlphaGo is simply stronger than any known human Go player.’ AlphaGo was seen to capably navigate tricky situations known as ko that did not come up in the previous two matches. An and Ormerod consider move 148 to be particularly notable: in the middle of a complex ko fight, AlphaGo displayed sufficient ‘confidence’ that it was winning the game to play a significant move elsewhere.

Lee won the fourth game. He chose to play a type of extreme strategy, known as amashi, in response to AlphaGo’s apparent preference for Souba Go (attempting to win by many small gains when the opportunity arises), taking territory at the perimeter rather than the center. By doing so, his apparent aim was to force an ‘all or nothing’ style of situation – a possible weakness for an opponent strong at negotiation types of play, and one which might make AlphaGo’s capability of deciding slim advantages largely irrelevant.

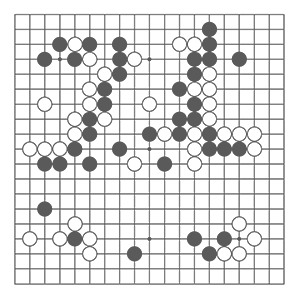

The first 11 moves were identical to the second game, where Lee also played white. In the early game, Lee concentrated on taking territory in the edges and corners of the board, allowing AlphaGo to gain influence in the top and centre. Lee then invaded AlphaGo’s region of influence at the top with moves 40 to 48, following the amashi strategy. AlphaGo responded with a shoulder hit at move 47, sacrificing four stones elsewhere and gaining the initiative with moves 47 to 53 and 69. Lee tested AlphaGo with moves 72 to 76 without provoking an error, and by this point in the game, commentators had begun to feel Lee’s play was a lost cause. However, an unexpected play at white 78, described as ‘a brilliant tesuji,’ turned the game around. The move developed a white wedge at the centre, and increased the game’s complexity. Gu Li (9p) described it as a ‘divine move’ and stated that the move had been completely unforeseen by him.

AlphaGo responded poorly on move 79, at which time it estimated it had a 70% chance to win the game. Lee followed up with a strong move at white 82. AlphaGo’s initial response in moves 83 to 85 was appropriate, but at move 87, its estimate of its chances to win suddenly plummeted, provoking it to make a series of very bad moves from black 87 to 101. David Ormerod characterized moves 87 to 101 as typical of Monte Carlo-based program mistakes. Lee took the lead by white 92, and An Younggil described black 105 as the final losing move. Despite good tactics during moves 131 to 141, AlphaGo could not recover during the endgame and resigned. AlphaGo’s resignation was triggered when it evaluated its chance of winning to be less than 20%; this is intended to match the decision of professionals who resign rather than play to the end when their position is felt to be irrecoverable.

An Younggil at Go Game Guru concluded that the game was ‘a masterpiece for Lee Sedol and will almost certainly become a famous game in the history of Go.’ Lee commented after the match that he considered AlphaGo was strongest when playing white (second). For this reason, he requested that he play black in the fifth game, which is considered more risky. David Ormerod of Go Game Guru stated that although an analysis of AlphaGo’s play around 79–87 was not yet available, he believed it resulted from a known weakness in play algorithms that use Monte Carlo tree search. In essence, the search attempts to prune less relevant sequences. In some cases, a play can lead to a particular line of play which is significant but which is overlooked when the tree is pruned, and this outcome is therefore ‘off the search radar.’

AlphaGo won the fifth game. The game was described as being close. Hassabis stated that the result came after the program made a ‘bad mistake’ early in the game. Lee, playing black, opened similarly to the first game and began to stake out territory in the right and top left corners – a similar strategy to the one he employed successfully in game 4 – while AlphaGo gained influence in the center of the board. The game remained even until white moves 48 to 58, which AlphaGo played in the bottom right. These moves unnecessarily lost ko threats and aji, allowing Lee to take the lead. Michael Redmond (9p) speculated that perhaps AlphaGo had missed black’s “tombstone squeeze” tesuji. Humans are taught to recognize the specific pattern, but it is a long sequence of moves, made difficult if computed from scratch.

AlphaGo then started to develop the top of the board and the center and defended successfully against an attack by Lee in moves 69 to 81 that David Ormerod characterized as over-cautious. By white 90, AlphaGo had regained equality and then played a series of moves described by Ormerod as ‘unusual… but subtly impressive,’ which gained a slight advantage. Lee tried a Hail Mary pass with moves 167 and 169, but AlphaGo’s defense was successful. An Younggil noted white moves 154, 186, and 194 as being particularly strong, and the program played an impeccable endgame, maintaining its lead until Lee resigned.

The Daily Omnivore

Everything is Interesting