Steganography [steg-uh-nog-ruh-fee] is the practice of representing information within another message or physical object, in such a manner that the presence of the concealed information would not be evident to an unsuspecting person’s examination.

The word steganography comes from Greek words steganós (‘covered or concealed’) and graphia (‘writing’). The first recorded use of the term was in 1499 by German Benedictine abbot Johannes Trithemius in his Steganographia, a treatise on cryptography and steganography, disguised as a book on magic.

In computing/electronic contexts, a computer file, message, image, or video is concealed within another file, message, image, or video. Generally, the hidden messages appear to be (or to be part of) something else: images, articles, shopping lists, or some other cover text. For example, the hidden message may be in invisible ink between the visible lines of a private letter. Some implementations of steganography that lack a formal shared secret are forms of security through obscurity, while key-dependent steganographic schemes try to adhere to Kerckhoffs’s principle (a cryptosystem should be secure, even if everything about the system, except the key, is public knowledge).

The advantage of steganography over cryptography alone is that the intended secret message does not attract attention to itself as an object of scrutiny. Plainly visible encrypted messages, no matter how unbreakable they are, arouse interest and may in themselves be incriminating in countries in which encryption is illegal. Whereas cryptography is the practice of protecting the contents of a message alone, steganography is concerned with concealing both the fact that a secret message is being sent and its contents.

In digital steganography, electronic communications may include steganographic coding inside of a transport layer, such as a document file, image file, program, or protocol. Media files are ideal for steganographic transmission because of their large size. For example, a sender might start with an innocuous image file and adjust the color of every hundredth pixel to correspond to a letter in the alphabet. The change is so subtle that someone who is not specifically looking for it is unlikely to notice the change.

The first recorded uses of steganography can be traced back to 440 BCE in Greece, when Herodotus mentions two examples in his Histories. Histiaeus sent a message to his vassal, Aristagoras, by shaving the head of his most trusted servant, ‘marking’ the message onto his scalp, then sending him on his way once his hair had regrown, with the instruction, ‘When thou art come to Miletus, bid Aristagoras shave thy head, and look thereon.’ Additionally, Demaratus sent a warning about a forthcoming attack to Greece by writing it directly on the wooden backing of a wax tablet before applying its beeswax surface. Wax tablets were in common use then as reusable writing surfaces, sometimes used for shorthand.

In his work Polygraphiae, German Benedictine abbot Johannes Trithemius developed his Ave Maria cipher that can hide information in a Latin praise of God.

Numerous techniques throughout history have been developed to embed a message within another medium. Placing the message in a physical item has been widely used for centuries. Some notable examples include invisible ink on paper, writing a message in Morse code on yarn worn by a courier, microdots, or using a music cipher to hide messages as musical notes in sheet music.

In communities with social or government taboos or censorship, people use cultural steganography—hiding messages in idiom, pop culture references, and other messages they share publicly and assume are monitored. This relies on social context to make the underlying messages visible only to certain readers. Examples include: hiding a message in the title and context of a shared video or image; misspelling names or words that are popular in the media in a given week, to suggest an alternative meaning; and hiding a picture that can be traced by using basic drawing tools.

Since the dawn of computers, techniques have been developed to embed messages in digital cover mediums. The message to conceal is often encrypted, then used to overwrite part of a much larger block of encrypted data or a block of random data (an unbreakable cipher like the one-time pad generates ciphertexts that look perfectly random without the private key).

Since the early 2000s, steganography research has evolved from focusing primarily on image-based techniques to addressing the challenges of hiding data in streaming media, particularly Voice over Internet Protocol (VoIP). This shift began with Giannoula’s frame-by-frame video data hiding in 2003, followed by Dittmann’s multimedia steganography work in 2005. Significant breakthroughs came from Huang and Tang, who pioneered Graph theory with Quantization Index Modulation for low bit-rate streaming media in 2008 and later developed real-time VoIP steganography algorithms (2011-2012).

Recent advancements include Cheddad & Cheddad’s 2024 framework combining steganography with machine learning for audio signal reconstruction, and the development of adaptive steganography techniques that tailor the embedding process to specific features of the cover medium, such as facial recognition for enhanced information hiding in images and videos.

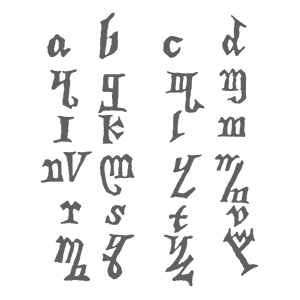

Digital steganography output may be in the form of printed documents. A message, the plaintext, may be first encrypted by traditional means, producing a ciphertext. Then, an innocuous cover text is modified in some way so as to contain the ciphertext, resulting in the stegotext. For example, the letter size, spacing, typeface, or other characteristics of a cover text can be manipulated to carry the hidden message. Only a recipient who knows the technique used can recover the message and then decrypt it. Francis Bacon developed Bacon’s cipher as such a technique.

The ciphertext produced by most digital steganography methods, however, is not printable. Traditional digital methods rely on perturbing noise in the channel file to hide the message, and as such, the channel file must be transmitted to the recipient with no additional noise from the transmission. Printing introduces much noise in the ciphertext, generally rendering the message unrecoverable. There are techniques that address this limitation, one notable example being ASCII Art Steganography.

Although not classic steganography, some types of modern color laser printers integrate the model, serial number, and timestamps on each printout for traceability reasons using a dot-matrix code made of small, yellow dots not recognizable to the naked eye.

Discussions of steganography generally use terminology analogous to and consistent with conventional radio and communications technology. However, some terms appear specifically in software and are easily confused. These are the most relevant ones to digital steganographic systems: The payload is the data covertly communicated. The carrier is the signal, stream, or data file that hides the payload, which differs from the channel, which typically means the type of input, such as a JPEG image. The resulting signal, stream, or data file with the encoded payload is sometimes called the package, stego file, or covert message. The proportion of bytes, samples, or other signal elements modified to encode the payload is called the encoding density and is typically expressed as a number between 0 and 1. In a set of files, the files that are considered likely to contain a payload are suspects. A suspect identified through some type of statistical analysis can be referred to as a candidate.

Detecting physical steganography requires a careful physical examination, including the use of magnification, developer chemicals, and ultraviolet light. It is a time-consuming process with obvious resource implications, even in countries that employ many people to spy on other citizens. However, it is feasible to screen mail of certain suspected individuals or institutions, such as prisons or prisoner-of-war (POW) camps.

During World War II, prisoner of war camps gave prisoners specially-treated paper that would reveal invisible ink. An article in a June 1948 issue of ‘Paper Trade’ Journal by the Technical Director of the United States Government Printing Office had Morris S. Kantrowitz describe in general terms the development of this paper. Three prototype papers (Sensicoat, Anilith, and Coatalith) were used to manufacture postcards and stationery provided to German prisoners of war in the U.S. and Canada. If POWs tried to write a hidden message, the special paper rendered it visible. A similar strategy issues prisoners with writing paper ruled with a water-soluble ink that runs in contact with water-based invisible ink.

In computing, steganographically encoded package detection is called steganalysis. The simplest method to detect modified files, however, is to compare them to known originals. For example, to detect information being moved through the graphics on a website, an analyst can maintain known clean copies of the materials and then compare them against the current contents of the site. The differences, if the carrier is the same, comprise the payload. In general, using extremely high compression rates makes steganography difficult but not impossible. Compression errors provide a hiding place for data, but high compression reduces the amount of data available to hold the payload, raising the encoding density, which facilitates easier detection (in extreme cases, even by casual observation).

There are a variety of basic tests that can be done to identify whether or not a secret message exists. This process is not concerned with the extraction of the message, which is a different process and a separate step. The most basic approaches of steganalysis are visual or aural attacks, structural attacks, and statistical attacks. These approaches attempt to detect the steganographic algorithms that were used.

It is possible to steganographically hide computer malware into digital images, videos, audio and various other files in order to evade detection by antivirus software. This type of malware is called stegomalware. It can be activated by external code, which can be malicious or even non-malicious if some vulnerability in the software reading the file is exploited.

Stegomalware can be removed from certain files without knowing whether they contain stegomalware or not. This is done through content disarm and reconstruction (CDR) software, and it involves reprocessing the entire file or removing parts from it. Actually detecting stegomalware in a file can be difficult and may involve testing the file behavior in virtual environments or deep learning analysis of the file.

Although steganography and digital watermarking seem similar, they are not. In steganography, the hidden message should remain intact until it reaches its destination. Steganography can be used for digital watermarking in which a message (being simply an identifier) is hidden in an image so that its source can be tracked or verified (for example, Coded Anti-Piracy) or even just to identify an image (as in the EURion constellation). In such a case, the technique of hiding the message (here, the watermark) must be robust to prevent tampering. However, digital watermarking sometimes requires a brittle watermark, which can be modified easily, to check whether the image has been tampered with. That is the key difference between steganography and digital watermarking.

In 2019 the U.S. Department of Justice unsealed an indictment charging Xiaoqing Zheng, a Chinese businessman and former Principal Engineer at General Electric, with 14 counts of conspiring to steal intellectual property and trade secrets from General Electric. Zheng had allegedly used steganography to exfiltrate 20,000 documents from General Electric to Tianyi Aviation Technology Co. in Nanjing, China, a company the FBI accused him of starting with backing from the Chinese government.

The Daily Omnivore

Everything is Interesting

Leave a comment