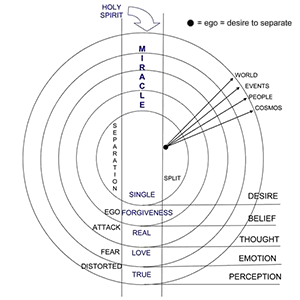

‘A Course in Miracles‘ (ACIM or simply the ‘Course’) is a book written and edited by psychologist Helen Schucman, with portions transcribed and edited by psychologist William Thetford, containing a self-study curriculum of spiritual transformation. It consists of three sections entitled ‘Text,’ ‘Workbook,’ and ‘Manual for Teachers.’ Written from 1965 to 1972, some distribution occurred via photocopies before a hardcover edition was published in 1976. The copyright and trademarks, which had been held by two foundations, were revoked in 2004 after a lengthy litigation because the earliest versions had been circulated without a copyright notice.

Schucman believed that an ‘inner voice,’ which she identified as Jesus, guided her writing. Throughout the 1980s annual sales of the book steadily increased each year, however the largest growth in sales occurred in 1992 after spiritual teacher Marianne Williamson discussed the book on ‘The Oprah Winfrey Show,’ with more than two million volumes sold. The book has been called everything from ‘a Satanic seduction’ to ‘The New Age Bible.’

read more »

A Course in Miracles

Shalom Bayit

Shalom [shuh-lohm] bayit [buy-eet] (Hebrew: ‘peace of the home’) is the Jewish religious concept of domestic harmony and good relations between husband and wife. In a Jewish court of law, shalom bayit is the Hebrew term for ‘marital reconciliation.’

Throughout the history of the Jewish people, Jews have held an ideal standard for Jewish family life that is manifested in the term shalom bayit. Shalom bayit signifies completeness, wholeness, and fulfillment. Hence, the ideal Jewish marriage is characterized by peace, nurturing, respect, and ‘chesed’ (roughly meaning ‘kindness,’ more accurately ‘loving-kindness’), through which a married couple becomes complete. The Jewish religion advocates that God’s presence dwells in a pure and loving home.

read more »

Wu Wei

Wu wei [woo-wey] is an important concept in Taoism that literally means non-action or non-doing. In the Chinese classic text the ‘Tao te Ching’ (‘Book of the Way and the Power’) Laozi explains that beings (or phenomena) that are wholly in harmony with the Tao (‘the Way’) behave in a completely natural, uncontrived way. The goal of spiritual practice for the human being is, according to Laozi, the attainment of this purely natural way of behaving. He likened it to the planets revolving around the the sun, without any sort of control, force, or attempt to revolve themselves, instead engaging in effortless and spontaneous movement.

Several chapters of the ‘Tao Te Ching’ allude to ‘diminishing doing’ or ‘diminishing will’ as the key aspect of the sage’s success. Taoist philosophy recognizes that the Universe already works harmoniously according to its own ways; as a person exerts their will against or upon the world they disrupt the harmony that already exists. This is not to say that a person should not exert agency and will. Rather, it is how one acts in relation to the natural processes already extant. The how, the Tao of intention and motivation, that is key. According to Laozi: ‘The Sage is occupied with the unspoken, and acts without effort. Teaching without verbosity, producing without possessing, creating without regard to result, claiming nothing, the Sage has nothing to lose.’

read more »

Pizza Effect

The pizza effect is a term used especially in religious studies and sociology for the phenomenon of elements of a nation or people’s culture being transformed or at least more fully embraced elsewhere, then re-imported back to their culture of origin, or the way in which a community’s self-understanding is influenced by (or imposed by, or imported from) foreign sources.

It is named after the idea that modern pizza was developed among Italian immigrants in the United States (rather than in native Italy where in its simpler form it was originally looked down upon), and was later exported back to Italy to be interpreted as a delicacy in Italian cuisine. Other culinary examples include chicken tikka masala, popularized in the UK before gaining prominence in India, and General Tso’s chicken, a dish unknown in China before it was introduced by chefs returning from the States.

read more »

Knocking on Wood

Knocking on wood, or to touch wood, refers to the apotropaic tradition (a ritual intended to ward off evil) of literally touching, tapping, or knocking on wood, or merely stating that you are doing or intend same, in order to avoid ‘tempting fate’ after making a favorable observation, a boast, or declaration concerning one’s own death or other situation beyond one’s control. The origin of this may be in Germanic folklore, wherein dryads (forest spirits) are thought to live in trees, and can be invoked for protection.

In Italy, ‘tocca ferro’ (‘touch iron’) is used, especially after seeing an undertaker or something related to death. In Iran, ‘bezan be takhteh’ (‘knock on the wood’) is said. The ‘evil eye,’ and being jinxed are common phobias and superstitions in Iranian culture. In old English folklore, ‘knocking on wood’ also referred to when people spoke of secrets – they went into the isolated woods to talk privately and ‘knocked’ on the trees when they were talking to hide their communication from evil spirits who would be unable to hear when they knocked. Another version holds that the act of knocking was to perk up the spirits to make them work in the requester’s favor. Yet another version holds that a sect of Monks who wore large wooden crosses around their necks would tap or ‘knock’ on them to ward away evil.

Lumpers and Splitters

Lumpers and splitters are opposing factions in any discipline which has to place individual examples into rigorously defined categories. The lumper-splitter problem occurs when there is the need to create classifications and assign examples to them, for example schools of literature, biological taxa and so on. ‘Lumpers’ take a gestalt view (looking at the whole rather than the parts) and assign examples broadly, assuming that differences are not as important as signature similarities. ‘Splitters’ prefer precise definitions, and create new categories to classify things that don’t fit perfectly within an existing group.

The earliest use of these terms was by Charles Darwin, in a letter to botanist J. D. Hooker in 1857: ‘Those who make many species are the ‘splitters,’ and those who make few are the ‘lumpers.’ They were introduced more widely by paleontologist George G. Simpson in his 1945 work ‘The Principles of Classification and a Classification of Mammals.’ As he put it, ‘splitters make very small units – their critics say that if they can tell two animals apart, they place them in different genera … and if they cannot tell them apart, they place them in different species. … Lumpers make large units – their critics say that if a carnivore is neither a dog nor a bear, they call it a cat.’

read more »

Metamagical Themas

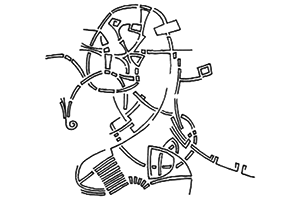

Metamagical [met-uh-maj-i-kuhl] Themas [thee-muhs] is an eclectic collection of articles that cognitive scientist Douglas Hofstadter wrote for ‘Scientific American’ during the early 1980s. The title is an anagram of Martin Gardner’s ‘Mathematical Games,’ the column that preceded Hofstadter’s. The anthology was published in 1985. Major themes include: self-reference in memes (ideas that spread within cultures), language, art and logic; discussions of philosophical issues important in cognitive science/AI; analogies and what makes something similar to something else (specifically what makes, for example, an uppercase letter ‘A’ recognizable as such); and lengthy discussions of the work of political scientist Robert Axelrod on the prisoner’s dilemma (a game theory problem).

There are three articles centered on the Lisp programming language, where Hofstadter first details the language itself, and then shows how it relates to Gödel’s incompleteness theorem. Two articles are devoted to Rubik’s Cube and other such puzzles. Many other topics are also mentioned, all in Hofstadter’s usual easy, approachable style. Many chapters open with an illustration of an extremely abstract alphabet, yet one which is still recognizable as such. The game of ‘Nomic’ (in which the rules of the game include mechanisms for the players to change those rules) was first introduced to the public in this column, in June 1982.

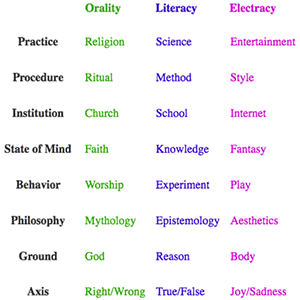

Electracy

Electracy [ee-lek-truh-see] is a theory by Gregory Ulmer, a professor of English and electronic languages, that describes the skills necessary to access and utilize electronic media such as multimedia (audio, visual, and text), hypermedia (linked material), social networks, and virtual worlds. According to Ulmer, electracy ‘is to digital media what literacy is to print.’ However, ‘If literacy focused on universally valid methodologies of knowledge (sciences), electracy focuses on the individual state of mind within which knowing takes place (arts).’ It is his attempt to describe the transition from a culture of print literacy to a culture saturated with electronic media.

Ulmer sees this shift as a positive step, writing, ‘The near absence of art in contemporary schools is the electrate equivalent of the near absence of science in medieval schools for literacy. The suppression of empirical inquiry by religious dogmatism during the era sometimes called the ‘dark ages’ (reflecting the hostility of the oral apparatus to literacy), is paralleled today by the suppression of aesthetic play by empirical utilitarianism (reflecting the hostility of the literate apparatus to electracy). The ambivalent relation of the institutions of school and entertainment today echoes the ambivalence informing church-science relations throughout the era of literacy.’ He concludes that the sociological changes will be profound: ‘What literacy is to the analytical mind, electracy is to the affective body: a prosthesis that enhances and augments a natural or organic human potential. Alphabetic writing is an artificial memory that supports long complex chains of reasoning impossible to sustain within the organic mind. Digital imaging similarly supports extensive complexes of mood atmospheres beyond organic capacity.’

Paradox of Tolerance

The tolerance paradox arises from a problem that a tolerant person might be antagonistic toward intolerance, hence intolerant of it. The tolerant individual would then be by definition intolerant of intolerance. American political philosopher Michael Walzer asks ‘Should we tolerate the intolerant?’ He notes that most minority religious groups who are the beneficiaries of tolerance are themselves intolerant, at least in some respects. In a tolerant regime, such people may learn to tolerate, or at least to behave ‘as if they possessed this virtue.’ Philosopher Karl Popper asserted, in ‘The Open Society and Its Enemies Vol. 1,’ that we are warranted in refusing to tolerate intolerance.

However, philosopher John Rawls concludes in ‘A Theory of Justice’ that a just society must tolerate the intolerant, for otherwise, the society would then itself be intolerant, and thus unjust. But, Rawls also insists, like Popper, that society has a reasonable right of self-preservation that supersedes the principle of tolerance: ‘While an intolerant sect does not itself have title to complain of intolerance, its freedom should be restricted only when the tolerant sincerely and with reason believe that their own security and that of the institutions of liberty are in danger.’

Origin Myth

An origin myth is a myth that purports to describe the origin of some feature of the natural or social world. One type of origin myth is the cosmogonic myth, which describes the creation of the world. However, many cultures have stories set after the cosmogonic myth, which describe the origin of natural phenomena and human institutions within a preexisting universe. In Western classical scholarship, the terms ‘etiological myth’ and ‘aition’ (Ancient Greek: ’cause’) are sometimes used for a myth that explains an origin, particularly how an object or custom came into existence.

Every origin myth is a tale of creation describing how some new reality came into existence. In many cases, origin myths also justify the established order by explaining that it was established by sacred forces. The distinction between cosmogonic myths and origin myths is not clear-cut. A myth about the origin of some part of the world necessarily presupposes the existence of the world—which, for many cultures, presupposes a cosmogonic myth. In this sense, one can think of origin myths as building upon and extending their cultures’ cosmogonic myths. In fact, in traditional cultures, the recitation of an origin myth is often prefaced with the recitation of the cosmogonic myth.

read more »

Master–Slave Morality

Master–slave morality is a central theme of German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche’s works, in particular the first essay of ‘On the Genealogy of Morality,’ his 1887 book ‘on the origin of our moral prejudices.’ Nietzsche argued that there were two fundamental types of morality: ‘Master morality’ and ‘slave morality’. Slave morality values things like kindness, humility and sympathy, while master morality values pride, strength, and nobility.

Master morality weighs actions on a scale of good or bad consequences unlike slave morality which weighs actions on a scale of good or evil intentions. What he meant by ‘morality’ deviates from common understanding of this term. For Nietzsche, a particular morality is inseparable from the formation of a particular culture. This means that its language, codes and practices, narratives, and institutions are informed by the struggle between these two types of moral valuation.

read more »

Prometheus Rising

‘Prometheus Rising‘ is a book by Robert Anton Wilson first published in 1983. It is a guide book of ‘how to get from here to there,’ an amalgam of psychonaut Timothy Leary’s 8-circuit model of consciousness, spiritualist Georges Gurdjieff’s self-observation exercises, Polish semiotician Alfred Korzybski’s general semantics, occultist Aleister Crowley’s magical theorems, Sociobiology (the study of the evolutionary bases of behavior), Yoga, relativity, and quantum mechanics among other approaches to understanding the world around us. Wilson describes it as an ‘owner’s manual for the human brain.’

The book, which examines many aspects of social mind control and mental imprinting, provides mind exercises at the end of every chapter, with the goal of giving the reader more control over how one’s mind works. Wilson also discusses the effect of certain psychoactive substances and how these affect the brain, tantric breathing techniques, and other methods and holistic approaches to expanding consciousness. The book’s take on transactional analysis became the main seed thought for ‘The Sekhmet Hypothesis’ (suggesting a link between the emergence of youth culture archetypes in relation to the 11 year solar cycle), specifically the idea of applying the life scripts to pop cultural trends.