Microbial intelligence is the intelligence shown by microorganisms, including complex adaptive behavior shown by single cells, and altruistic and/or cooperative behavior in populations of like or unlike cells. While the number of microorganisms in a colony can run into the billions, each individual is able to stay synchronized by sharing simple chemical messages. Complex cells, like protozoa or algae, show remarkable abilities to organize themselves in changing circumstances. Shell-building by amoebae, reveals complex discrimination and manipulative skills that are ordinarily thought to occur only in multicellular organisms.

Even bacteria, which show primitive behavior as isolated cells, can display more sophisticated behavior as a population. Examples include: myxobacteria (which form motile slime colonies), quorum sensing (a system of stimulus and response correlated to population density), and biofilms (cells that cooperate to stick to each other on a surface). It has been suggested that a bacterial colony loosely mimics a biological neural network (i.e. a brain). The bacteria can take inputs in form of chemical signals, process them and then produce output chemicals to signal other bacteria in the colony.

read more »

Microbial Intelligence

Swarm Intelligence

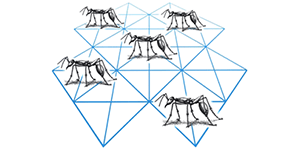

Swarm Intelligence (SI) refers to numerous, simple units working in concert to solve complex problems. It is field in computer science and artificial intelligence based on examples from nature such as an ant colony, made of many animals that communicate with each other to achieve unified goals. In computer models the ‘animals,’ or individual units, are called ‘agents.’ Swarm intelligence emerges from decentralized, self-organizing systems, natural or artificial. The expression was introduced by electrical engineers Gerardo Beni and Jing Wang in 1989, in the context of cellular robotic systems. The application of swarm principles to robots is called ‘swarm robotics,’ while ‘swarm intelligence’ refers to the more general set of algorithms. ‘Swarm prediction’ has been used in the context of forecasting problems.

SI systems consist typically of a population of simple agents or ‘boids’ (named for a 1986 artificial life program that simulates the flocking behavior of birds) interacting locally with one another and with their environment. A number of natural systems have been used as models (e.g. animal herding, bacterial growth, fish schooling and microbial intelligence). The agents follow very simple rules, and although there is no centralized control structure dictating how each unit should behave, local, and to a certain degree random, interactions between such agents lead to the emergence of ‘intelligent’ global behavior, unknown to the individuals.

read more »

Gamma Wave

Neural oscillation is rhythmic or repetitive neural activity in the central nervous system. For example Delta waves (0-4 Hz on an EEG) is the lowest frequency neural oscillation and is associated with deep sleep. Gamma waves are the highest frequency pattern at 25-100 Hz (though 40 Hz is typical), and according to a popular theory, they may be related to subjective awareness.

Gamma waves were initially ignored before the development of digital electroencephalography as analog electroencephalography is restricted to recording and measuring rhythms that are usually less than 25 Hz. One of the earliest reports on them was in 1964 using recordings of the electrical activity of electrodes implanted in the visual cortex of awake monkeys.

read more »

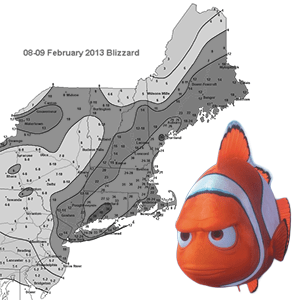

Winter Storm Naming

Winter storm naming in the United States has been used by The Weather Channel (TWC) since 2011, when the cable network informally used the previously-coined name ‘Snowtober’ for a 2011 Halloween nor’easter. In November 2012, TWC began systematically naming winter storms, starting with the November 2012 nor’easter it named ‘Winter Storm Athena.’ TWC compiled a list of winter storm names for the 2012–13 winter season. It would only name those storms that are ‘disruptive’ to people, said Bryan Norcross, a TWC senior director. TWC’s decision was met with criticism from other weather forecasters, who called the practice self-serving and potentially confusing to the public.

The U.S. government-operated National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) (a division of which–the National Hurricane Center–has named hurricanes for many years) and its main division–the National Weather Service (NWS)–did not acknowledge TWC’s winter storm names and asked its forecast offices to refrain from using them. The NWS spokesperson Susan Buchanan stated, ‘The National Weather Service does not name winter storms because a winter storm’s impact can vary from one location to another, and storms can weaken and redevelop, making it difficult to define where one ends and another begins.’

Escalation of Commitment

Escalation of commitment was first described by business professor Barry M. Staw in his 1976 paper, ‘Knee deep in the big muddy: A study of escalating commitment to a chosen course of action.’ More recently the term ‘sunk cost fallacy’ has been used to describe the phenomenon where people justify increased investment in a decision, based on the cumulative prior investment, despite new evidence suggesting that the cost, starting today, of continuing the decision outweighs the expected benefit. Such investment may include money, time, or even — in the case of military strategy— human lives (the term has been used to describe the US commitment to military conflicts including Vietnam and Iraq).

The phenomenon and the sentiment underlying it are reflected in such proverbial images as ‘Throwing good money after bad,’ ‘In for a dime, in for a dollar,’ or ‘In for a penny, in for a pound.’ A common example irrational escalation is a bidding war; the bidders can end up paying much more than the object is worth to justify the initial expenses associated with bidding (such as research), as well as part of a competitive instinct. The main drivers of the tendency to invest in losing propositions are: Social (peer pressure), Psychological (gambling), Project (past commitments), and Structural (cultural and environmental factors). After a heated bidding war, Canadian financier Robert Campeau ended up buying Bloomingdale’s for an estimated $600 million more than it was worth. The ‘Wall Street Journal’ noted that ‘we’re not dealing in price anymore but egos.’ Campeau was forced to declare bankruptcy soon afterwards.

Downwind Faster than the Wind

Sailing faster than the wind is the technique by which vehicles that are powered by sails (such as sailboats, iceboats and sand yachts) advance over the surface on which they travel faster than the wind that powers them. Typically, such devices cannot travel faster than the wind when sailing dead downwind using simple square sails that are set perpendicular to the wind. They require sails set at an angle to the wind, which utilizes the lateral resistance of the surface on which they sail (for example the water or the ice) to maintain a course at some other angle to the wind.

For those craft it is impossible to sail dead downwind faster than the wind because the apparent wind will be zero if the speed of the vehicle equals the speed of the wind. However, certain sailing craft (such as ice boats and high performance catamarans) can achieve overall downwind speeds faster than the wind by tacking back and forth across the wind: they do this by using the surface on which they sail to capture the energy of the wind. Similarly, it is possible to sail dead downwind faster than the wind if a mechanical device is used to transfer energy from the surface on which the machine is moving in order to capture the energy of the wind and use it (not through a sail). By using a propeller instead of a conventional sail, and coupling the propeller to its wheels, a land yacht can proceed dead downwind faster than the wind.

read more »

Prosecutor’s Fallacy

The prosecutor’s fallacy is a fallacy of statistical reasoning, typically used by the prosecution to argue for the guilt of a defendant during a criminal trial (though some variants are utilized by defense lawyers arguing for the innocence of their client). The fallacy involves assuming that the prior probability of a random match is equal to the probability that the defendant is innocent. For instance, if a perpetrator is known to have the same blood type as a defendant and 10% of the population share that blood type, then to argue on that basis alone that the probability of the defendant being guilty is 90% makes the prosecutors’s fallacy.

Consider the case of a lottery winner accused of cheating based on the improbability of winning. At the trial, the prosecutor calculates the (very small) probability of winning the lottery without cheating and argues that this is the chance of innocence. The logical flaw is that the prosecutor has failed to account for the large number of people who play the lottery.

read more »

Sensory Substitution

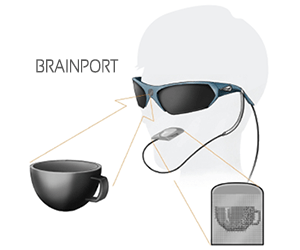

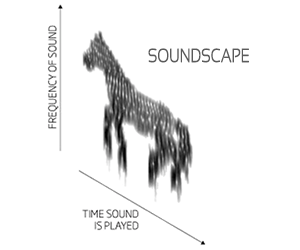

Sensory substitution means to transform the characteristics of one sensory modality (e.g. light, sound, temperature, taste, pressure, smell) into stimuli of another sensory modality (e.g. Tactile–Visual, converting video footage into into tactile information, such as vibration). These systems can help handicapped people by restoring their ability to perceive aspects of a defective physical sense.

A sensory substitution system consists of three parts: a sensor, a coupling system, and a stimulator. The sensor records stimuli and gives them to a coupling system which interprets the signals and transmits them to a stimulator. If the sensor obtains signals of a kind not originally available to the bearer it is called ‘sensory augmentation’ (e.g. implanting magnets under the fingertips imparts magnetoception, sensation of electromagnetic fields). Sensory substitution is based on research in human perception (the organization, identification, and interpretation of sensory information in order to represent and understand the environment) and neuroplasticity (how entire brain structures, and the brain itself, can change from experience).

read more »

Galvanic Vestibular Stimulation

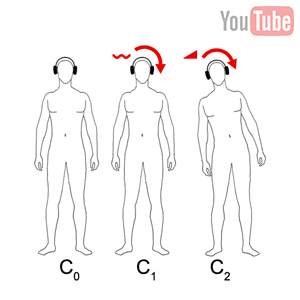

Galvanic [gal-van-ik] vestibular [ve-stib-yuh-ler] stimulation (GVS) is the process of sending electric messages to a nerve in the ear that maintains balance. This technology has been investigated for both military and commercial purposes, and is being applied in Atsugi, Japan, the Mayo Clinic in the US, and a number of other research institutions around the world for use in biomedical engineering, pilot training, and entertainment.

A patient undergoing GVS noted: ‘I felt a mysterious, irresistible urge to start walking to the right whenever the researcher turned the switch to the right. I was convinced — mistakenly — that this was the only way to maintain my balance. The phenomenon is painless but dramatic. Your feet start to move before you know it. I could even remote-control myself by taking the switch into my own hands.’

Biomimicry

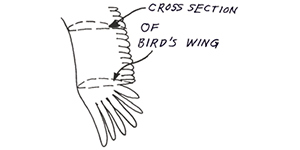

Biomimicry [bahy-oh-mim-ik-ree] is the imitation of biological systems in human technology. Living organisms have evolved well-adapted structures and materials over geological time through natural selection. Nature has solved engineering problems such as self-healing, environmental exposure tolerance, hydrophobicity (waterproofing), self-assembly, and harnessing solar energy.

One of the early examples of biomimicry was the study of birds to enable human flight. Although never successful in creating a ‘flying machine,’ Leonardo da Vinci (1452–1519) was a keen observer of the anatomy and flight of birds, and made numerous notes and sketches on his observations as well as designs of rudimentary ornithopters based on bats. The Wright Brothers, who succeeded in flying the first heavier-than-air aircraft in 1903, derived inspiration from observations of pigeons in flight. Their airfoil was based on a design by German ‘Glider King’ Otto Lilienthal who published ‘Birdflight as the Basis of Aviation.’ Velcro, another famous example, was inspired by the tiny hooks found on the surface of burs.

read more »

Handedness

Handedness [han-did-nis] is a better (faster or more precise) performance or individual preference for use of a hand. It is not a discrete variable (right or left), but a continuous one that can be expressed at levels between strong left and strong right. While in an ordinary disclosure the terms left and right are used to define handedness, there are actually four types: left-handedness, right-handedness, mixed-handedness (favoring one hand for some tasks and the other hand for others), and ambidexterity (equally adept with both hands). Left-handedness is somewhat more common among men.

Global studies indicate that 10% of people are left-handed, 30% are mixed-handed, and the remainder are right-handed. Ambidexterity is exceptionally rare, although it can be learned. However, a truly ambidextrous person is able to do any task equally well with either hand, whereas those who learn it still tend to favor their originally dominant hand. Ambilevous or ambisinister people demonstrate awkwardness with both hands. Parkinson’s disease in particular is associated with a loss of dexterity.

read more »

Lumpers and Splitters

Lumpers and splitters are opposing factions in any discipline which has to place individual examples into rigorously defined categories. The lumper-splitter problem occurs when there is the need to create classifications and assign examples to them, for example schools of literature, biological taxa and so on. ‘Lumpers’ take a gestalt view (looking at the whole rather than the parts) and assign examples broadly, assuming that differences are not as important as signature similarities. ‘Splitters’ prefer precise definitions, and create new categories to classify things that don’t fit perfectly within an existing group.

The earliest use of these terms was by Charles Darwin, in a letter to botanist J. D. Hooker in 1857: ‘Those who make many species are the ‘splitters,’ and those who make few are the ‘lumpers.’ They were introduced more widely by paleontologist George G. Simpson in his 1945 work ‘The Principles of Classification and a Classification of Mammals.’ As he put it, ‘splitters make very small units – their critics say that if they can tell two animals apart, they place them in different genera … and if they cannot tell them apart, they place them in different species. … Lumpers make large units – their critics say that if a carnivore is neither a dog nor a bear, they call it a cat.’

read more »