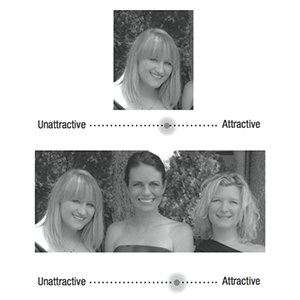

The cheerleader effect, also known as the group attractiveness effect, is the cognitive bias which causes people to think individuals are more attractive when they are in a group. The concept has been backed up by clinical research by psychologists Drew Walker and Edward Vul. The effect occurs because of the brain’s tendency to calculate the average properties of an object when viewing a group.

Walker and Vul proposed that this effect arises due to the interplay of three cognitive phenomena: the human visual system takes ‘ensemble representations’ of faces in a group; perception of individuals is biased towards this average; average faces are more attractive, perhaps due to ‘averaging out of unattractive idiosyncrasies.’

read more »

Cheerleader Effect

Hedgehog’s Dilemma

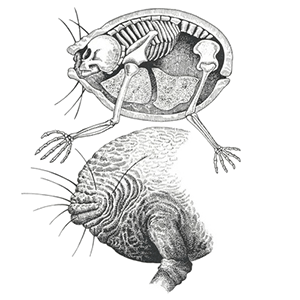

The hedgehog’s dilemma is a metaphor about the challenges of human intimacy. It describes a situation in which a group of hedgehogs all seek to become close to one another in order to share heat during cold weather. They must remain apart, however, as they cannot avoid hurting one another with their sharp spines. Though they all share the intention of a close reciprocal relationship, this may not occur, for reasons they cannot avoid.

German philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer and psychoanalyst Sigmund Freud have used this situation to describe what they feel is the state of the individual in relation to others in society. The hedgehog’s dilemma suggests that despite goodwill, human intimacy cannot occur without substantial mutual harm, and what results is cautious behavior and weak relationships. The hedgehog’s dilemma demands moderation in affairs with others both because of self-interest, as well as out of consideration for others, leading to introversion and isolationism.

read more »

Anomalistics

Anomalistics [uh-nom-uh-list-iks] is the use of scientific methods to evaluate anomalies (phenomena that fall outside of current understanding), with the aim of finding a rational explanation. The term itself was coined in 1973 by Drew University anthropologist Roger W. Wescott, who defined it as being the ‘serious and systematic study of all phenomena that fail to fit the picture of reality provided for us by common sense or by the established sciences.’

Wescott credited journalist and researcher Charles Fort as being the creator of anomalistics as a field of research, and he named biologist Ivan T. Sanderson and ‘Sourcebook Project’ compiler William R. Corliss as being instrumental in expanding anomalistics to introduce a more conventional perspective into the field. Anomalistics covers several sub-disciplines, including ufology (the study of unidentified flying objects), cryptozoology (the study of hidden animals), and parapsychology (the study of psychic events).

read more »

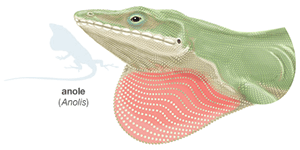

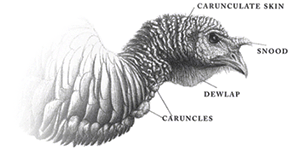

Dewlap

A dewlap [doo-lap] is a longitudinal flap of skin that hangs beneath the lower jaw or neck of many vertebrates. While the term is usually used in this specific context, it can also be used to include other structures occurring in the same body area with a similar aspect, such as those caused by a double chin or the submandibular vocal sac of a frog. In a more general manner, the term refers to any pendulous mass of skin, such as a fold of loose skin on an elderly person’s neck, or the wattle of a bird, a drooping protuberance hanging from various parts of the head or neck.

Many reptiles have dewlaps, most notably the anole species of lizard, which have large skin dewlaps which they can extend and retract. These dewlaps are usually of a different color from the rest of their body and when enlarged make the lizard seem much larger. They display them when indicating territorial boundaries and to attract females. Lizards usually accompany their dewlap movement with head bobs and other displays. Though much uncertainty resides around the purpose of these displays, the color of the dewlap and the head bobs are thought to be a means of contrasting background noise.

read more »

Red Mercury

Red mercury is a hoax substance of uncertain composition purportedly used in the creation of nuclear bombs, as well as a variety of unrelated weapons systems. It is purported to be mercuric iodide, a poisonous, odorless, tasteless, water-insoluble scarlet-red powder that becomes yellow when heated above 126 °C (258 °F), due to a thermochromatic change in crystalline structure.

However, samples of ‘red mercury’ obtained from arrested would-be terrorists invariably consisted of nothing more than various red dyes or powders of little value, which some suspect was being sold as part of a campaign intended to flush out potential nuclear smugglers. The hoax was first reported in 1979 and was commonly discussed in the media in the 1990s. Prices as high as $1,800,000 per kilogram were reported.

read more »

Whispering Gallery

A whispering gallery is a circular room in which whispers can be heard clearly across great distances. The sound is carried by waves, known as ‘whispering-gallery waves,’ that travel around the circumference clinging to the walls, an effect that was discovered in the whispering gallery of St Paul’s Cathedral in London. Other historical examples are the Gol Gumbaz mausoleum in India and the Echo Wall of the Temple of Heaven in Beijing.

The gallery may also be in the form of an ellipse or ellipsoid, with an accessible point at each focus. In this case, when a visitor stands at one focus and whispers, the line of sound emanating from this focus reflects directly to the focus at the other end of the gallery, where the whispers may be heard. In a similar way, two large concave parabolic dishes, serving as acoustic mirrors, may be erected facing each other in a room or outdoors to serve as a whispering gallery, a common feature of science museums. Egg-shaped galleries, such as the Golghar Granary in India, and irregularly shaped smooth-walled galleries in the form of caves, such as the Ear of Dionysius in Syracuse, also exist.

Nudge Theory

Nudge theory is a concept in behavioral economics which argues that positive reinforcement and indirect suggestions promoting non-forced compliance can influence the motives, incentives, and decision making of groups and individuals, at least as effectively – if not more effectively – than direct instruction, legislation, or enforcement. The theory came to prominence with a 2008 book, ‘Nudge: Improving Decisions About Health, Wealth, and Happiness’ by behavioral economists Richard Thaler and Cass Sunstein.

They defined a ‘nudge’ as: ‘any aspect of the choice architecture that alters people’s behavior in a predictable way without forbidding any options or significantly changing their economic incentives. To count as a mere nudge, the intervention must be easy and cheap to avoid. Nudges are not mandates. Putting fruit at eye level counts as a nudge. Banning junk food does not.’ One of nudges’ most frequently cited examples is the etching of the image of a housefly into the men’s room urinals at Amsterdam’s Schiphol Airport, which is intended to ‘improve the aim.’

Man After Man

‘Man After Man: An Anthropology of the Future’ is a 1990 book written by Scottish geologist Dougal Dixon exploring future evolutionary paths for humanity. Illustrator Philip Hood’s depictions of Dixon’s speculative organisms have been called fear-provoking and biologically horrific to the modern eye.

The book starts 200 years in the future where modern humans have genetically modified themselves into several subtypes including ‘aquamorphs’ (marine humans with gills instead of lungs) and ‘vacuumorphs’ (engineered for life in the vacuum of space, its skin and eyes carry shields of skin to keep its body stable even without pressure).

read more »

Neurotheology

Neurotheology [noor-oh-thee-ol-uh-jee], also known as ‘spiritual neuroscience’ or ‘neuroscience of religion,’ attempts to explain religious experience and behavior scientifically. It is the study of correlations of neural phenomena with subjective experiences of spirituality and hypotheses to explain these phenomena.

Researchers in the field attempt to explain the neurological basis for religious experiences, such as: spiritual awe, the feeling of oneness with the universe, ecstatic trances, sudden enlightenment, and other spiritually motivated altered states of consciousness. English writer and philosopher Aldous Huxley used the term ‘neurotheology’ for the first time in the utopian novel ‘Island.’

read more »

Culture of Honor

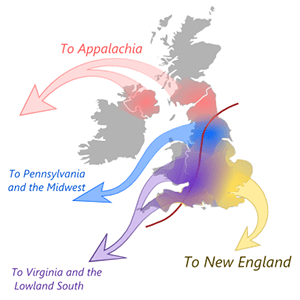

The traditional culture of the Southern United States has been called a ‘culture of honor,’ where people avoid intentionally offending others, and maintain a reputation for not accepting improper conduct by others. A prevalent theory as to why the American South had or may have this culture is an assumed regional belief in retribution to enforce one’s rights and deter predation against one’s family, home, and possessions.

Southern culture is thought to have its roots in the livelihoods of the early settlers who first inhabited the region. New England was mostly comprised of agriculturalist colonists from densely populated South East England and East Anglia, but the Southern United States was mostly settled by herders from Scotland, Northern Ireland, Northern England, and the West Country. Herds, unlike crops, are vulnerable to theft because they are mobile and there is little government wherewithal to enforce property rights of herd animals. A reputation for violent retribution against those who stole animals was a necessary deterrent at the time.

read more »

Mr. Wizard

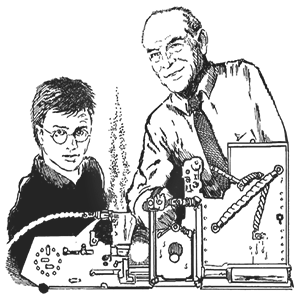

Don Herbert (1917 – 2007) was the creator and host of educational television programs for children devoted to science and technology, notably ‘Watch Mr. Wizard’ (1951–65, 1971–72) and ‘Mr. Wizard’s World’ (1983–90). He also produced many short video programs about science and authored several popular books about science for children. Marcel LaFollette of the Smithsonian notes that no fictional hero was able to rival the popularity and longevity of ‘the friendly, neighborly scientist.’

In Herbert’s obituary, Bill Nye wrote, ‘Herbert’s techniques and performances helped create the United States’ first generation of homegrown rocket scientists just in time to respond to Sputnik. He sent us to the moon. He changed the world.’ Herbert is credited with turning ‘a generation of youth’ in the 1950s and early 1960s onto ‘the promise and perils of science.’

read more »