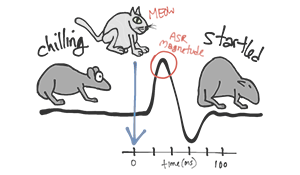

The startle response is a brainstem reflectory reaction (reflex) that serves to protect the back of the neck (whole-body startle) and the eyes (eyeblink) and facilitates escape from sudden stimuli. It is found across the lifespan of many species. An individual’s emotional state may lead to a variety of responses. The acoustic startle reflex is thought to be caused by an auditory stimulus greater than 80 decibels.

The anterior cingulate cortex in the brain is largely thought to be the main area associated with emotional response and awareness, which can contribute to the way an individual reacts to a startle inducing stimuli. Along with the anterior cingulate cortex, the amygdala and the hippocampus are known to have implications in this reflex. The amygdala is known to have a role in the ‘fight or flight’ response, and the hippocampus functions to form memories of the stimulus and the emotions associated with it.

Startle Response

Baker-Miller Pink

Baker-Miller Pink is a tone of pink that was originally created by mixing one gallon of pure white indoor latex paint with one pint of red trim semi-gloss outdoor paint. It is named for the two US Navy officers who first experimented with its use in the Naval Correctional Facility in Seattle, Washington at the behest of researcher Alexander Schauss. The color is also known as Schauss pink, after Alexander Schauss’s extensive research into the effects of the color on emotions and hormones, as well as P-618 and ‘Drunk-Tank Pink’ (so named because jails cells are painted this color because it is believed to calm inmates).

Contemporary research has shown conflicting results on the effects of Baker-Miller pink. While the initial results at the Naval Correctional facility in Seattle were positive, calming those exposed, inmates at the Santa Clara county jail were trying to scratch the paint from the walls with their fingernails when exposed for more than fifteen minutes. At Johns Hopkins, appetite suppression was observed and studied.

read more »

Phantom Vibration Syndrome

Phantom vibration syndrome or ‘phantom ringing’ is the mistaken feeling that one’s mobile phone is vibrating or ringing. Other terms for this concept include ringxiety (a portmanteau of ‘ring’ and ‘anxiety’) and ‘fauxcellarm’ (a play on ‘false alarm’). It is a form of pareidolia, a psychological phenomenon involving a stimulus (such as an image or a sound) wherein the mind perceives a familiar pattern where none actually exists. Phantom ringing may be experienced while taking a shower, watching television, or using a noisy device. Humans are particularly sensitive to auditory tones between 1,000 and 6,000 hertz, and basic mobile phone ringers often fall within this range.

In the comic strip ‘Dilbert,’ cartoonist Scott Adams referenced such a sensation in 1996 as ‘phantom-pager syndrome.’ The earliest published use of the term dates to a 2003 article in the ‘New Pittsburgh Courier,’ written by Robert D. Jones. In the conclusion of the article, Jones writes, ‘…should we be concerned about what our mind or body may be trying to tell us by the aggravating imaginary emanations from belts, pockets and even purses? Whether PVS is the result of physical nerve damage, a mental health issue, or both, this growing phenomenon seems to indicate that we may have crossed a line in this ‘always on’ society.’

Vacuum Activity

Vacuum activities are innate, fixed action patterns of animal behavior that are performed in the absence of the external stimuli (releaser) that normally elicit them. This type of abnormal behavior shows that a key stimulus is not always needed to produce an activity. Vacuum activities can be difficult to identify because it is necessary to determine whether any stimulus triggered the behavior.

For example, squirrels that have lived in metal cages without bedding all their lives do all the actions that a wild squirrel does when burying a nut. It scratches at the metal floor as if digging a hole, it acts as if it were taking a nut to the place where it scratched though there is no nut, then it pats the metal floor as if covering an imaginary buried nut.

read more »

Double Bind

A double bind is an emotionally distressing dilemma in communication in which an individual (or group) receives two or more conflicting messages, and one message negates the other. This creates a situation in which a successful response to one message results in a failed response to the other (and vice versa), so that the person will automatically be wrong regardless of response. The double bind occurs when the person cannot confront the inherent dilemma, and therefore can neither resolve it nor opt out of the situation.

The classic example given of a negative double bind is of a mother telling her child that she loves him or her, while at the same time turning away in disgust (the words are socially acceptable; the body language is in conflict with it). The child doesn’t know how to respond to the conflict between the words and the body language and, because the child is dependent on the mother for basic needs, he or she is in a quandary. Small children have difficulty articulating contradictions verbally and can neither ignore them nor leave the relationship.

read more »

Explanatory Style

Explanatory style is a psychological attribute that indicates how people explain to themselves why they experience a particular event, either positive or negative. There are three main components: Personal (internal vs. external), Permanent (stable vs. unstable), and Pervasive (global vs. local/specific).

‘Personalization’ refers to how one explains the cause of an event. People experiencing events may see themselves as the cause; that is, they have internalized the cause for the event (e.g. ‘I always forget to make that turn,’ as opposed to, ‘That turn can sure sneak up on you’). ‘Permanenence’ describes how one explains the extent of the cause. People may see a situation as unchangeable (e.g., ‘I always lose my keys’ or ‘I never forget a face’). ‘Pervasiveness’ measures how one explains the extent of the effects. People may see a situation as affecting all aspects of life (e.g., ‘I can’t do anything right’ or ‘Everything I touch seems to turn to gold’).

read more »

Character Strengths and Virtues

‘Character Strengths and Virtues‘ (CSV) is a 2004 book by psychologists Christopher Peterson and Martin Seligman that presents humanist ideals of virtue in an empirical, rigorously scientific manner. Seligman describes it as a ‘positive’ counterpart to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM). While the DSM focuses on what can go wrong, CSV is designed to look at what can go right.

In their research they looked across cultures and time to distill a manageable list of virtues that have been highly valued from ancient China and India, through Greece and Rome, to contemporary Western cultures. Their list includes six character strengths: wisdom/knowledge, courage, humanity, justice, temperance, and transcendence. Each of these has three to five sub-entries; for instance, temperance includes forgiveness, humility, prudence, and self-regulation. The authors do not believe that there is a hierarchy for the six virtues; no one is more fundamental than or a precursor to the others.

read more »

Metabolism

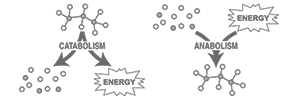

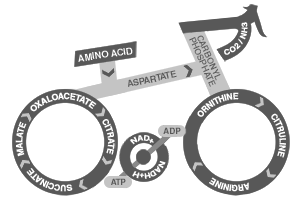

Metabolism [muh-tab-uh-liz-uhm] is the name given to the chemical reactions which keep an organism alive. A chemical reaction is the transformation of one set of chemical substances to another. Organisms require myriad reactions to grow, reproduce, maintain their structures, and respond to their environments. These reactions are catalyzed by enzymes (aided by reusable proteins that change the rate of chemical reactions).

Most of the structures that make up animals, plants, and microbes are made from three basic classes of molecule: amino acids (the building blocks of proteins), carbohydrates (sugars), and lipids (fats). As these molecules are vital for life, metabolic reactions either focus on making these molecules during the construction of cells and tissues (anabolism), or by breaking them down and using them as a source of energy, by their digestion (catabolism).

read more »

Greedy Reductionism

Greedy reductionism [ri-duhk-shuh-niz-uhm] is a term coined by cognitive scientist Daniel Dennett, in his 1995 book ‘Darwin’s Dangerous Idea,’ to refer to a kind of erroneous reductionism. Whereas ‘good’ reductionism means explaining a thing in terms of what it reduces to (for example, its parts and their interactions), greedy reductionism occurs when ‘in their eagerness for a bargain, in their zeal to explain too much too fast, scientists and philosophers … underestimate the complexities, trying to skip whole layers or levels of theory in their rush to fasten everything securely and neatly to the foundation.’

Using the terminology of ‘cranes’ (legitimate, mechanistic explanations) and ‘skyhooks’ (essentially, fake—e.g. supernaturalistic—explanations), Dennett states: ‘Good reductionists suppose that all Design can be explained without skyhooks; greedy reductionists suppose it can all be explained without cranes.’

read more »

Illusory Correlation

Illusory [ih-loo-suh-ree] correlation [kawr-uh-ley-shuhn] is the phenomenon of perceiving a relationship between variables (typically people, events, or behaviors) even when no such relationship exists. A common example of this phenomenon would be when people form false associations between membership in a statistical minority group and rare (typically negative) behaviors as variables that are novel or salient tend to capture the attention. This is one way stereotypes form and endure, which can lead people to expect certain groups and traits to fit together, and then to overestimate the frequency with which these correlations actually occur.

The term ‘Illusory correlation’ was originally coined in 1967 by psychologists Loren Chapman and Jean Chapman to describe people’s tendencies to overestimate relationships between two groups when distinctive and unusual information is presented. The concept was used to question claims about objective knowledge in clinical psychology through the Chapmans’ refutation of many clinicians’ widely used Wheeler signs for homosexuality in Rorschach tests.

read more »

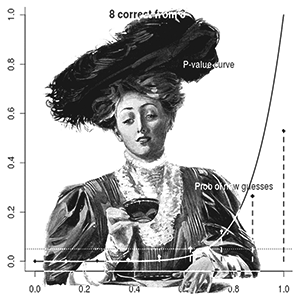

Lady Tasting Tea

In the design of experiments in statistics, the lady tasting tea is a famous randomized experiment devised by English statisticia Ronald A. Fisher and reported in his book ‘The Design of Experiments’ (1935). The experiment is the original exposition of Fisher’s notion of a ‘null hypothesis’ (what you expect to happen before you run an experiment, i.e. nothing). Fisher’s description is less than ten pages in length and is notable for its simplicity and completeness regarding terminology, calculations, and design of the experiment. The example is loosely based on an event from his life. The lady in question was biologist Muriel Bristol.

Bristol claimed to be able to tell whether the tea or the milk was added first to her daily cup of tea. Fisher proposed to give her eight cups, four of each variety, in random order. One could then ask what the probability was for her getting the number she got correct, but just by chance. She got all eight cups correct. In popular science, David Salsburg published a book entitled ‘The Lady Tasting Tea,’ which describes Fisher’s experiment and ideas on randomization.

Grit

Grit in psychology is a positive, non-cognitive trait based on an individual’s passion for a particular long-term goal or endstate, coupled with a powerful motivation to achieve their respective objective. This perseverance of effort promotes the overcoming of obstacles or challenges that lie within a gritty individual’s path to accomplishment, and serves as a driving force in achievement realization. Commonly associated concepts within the field of psychology include ‘perseverance,’ ‘hardiness,’ ‘resilience,’ ‘ambition,’ ‘need for achievement,’ and ‘conscientiousness.’ These constructs can be conceptualized as individual differences related to the accomplishment of work rather than latent ability.

This distinction was brought into focus in 1907 when American psychologist William James challenged the field to further investigate how certain individuals are capable of accessing richer trait reservoirs enabling them to accomplish more than the average person, but the construct dates back at least to Victorian polymath Francis Galton, and the ideals of persistence and tenacity have been understood as a virtue at least since Aristotle. Although the last decade has seen a noticeable increase in research focused on achievement-oriented traits, there continues to be difficulty in aligning specific traits and outcomes.

read more »