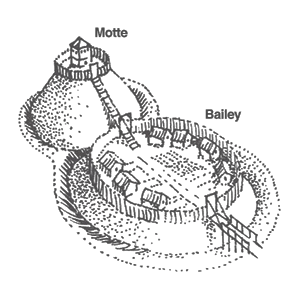

The motte-and-bailey fallacy (named after the motte-and-bailey castle) is a form of argument and an informal fallacy where an arguer conflates two positions that share similarities, one modest and easy to defend (the ‘motte’) and one much more controversial and harder to defend (the ‘bailey’).

The arguer advances the controversial position, but when challenged, insists that only the more modest position is being advanced. Upon retreating to the motte, the arguer can claim that the bailey has not been refuted (because the critic refused to attack the motte) or that the critic is unreasonable (by equating an attack on the bailey with an attack on the motte).

read more »

Motte-and-Bailey Fallacy

Slippery Slope

A slippery slope argument (SSA), in logic, critical thinking, political rhetoric, and caselaw, is a consequentialist logical device in which a party asserts that a relatively small first step leads to a chain of related events culminating in some significant (usually negative) outcome.

The core of the slippery slope argument is that a specific decision under debate is likely to result in unintended consequences. The strength of such an argument depends on the warrant, i.e. whether or not one can demonstrate a process that leads to the significant effect. This type of argument is sometimes used as a form of fear mongering, in which the probable consequences of a given action are exaggerated in an attempt to scare the audience.

read more »

Prosecutor’s Fallacy

The prosecutor’s fallacy is a fallacy of statistical reasoning, typically used by the prosecution to argue for the guilt of a defendant during a criminal trial (though some variants are utilized by defense lawyers arguing for the innocence of their client). The fallacy involves assuming that the prior probability of a random match is equal to the probability that the defendant is innocent. For instance, if a perpetrator is known to have the same blood type as a defendant and 10% of the population share that blood type, then to argue on that basis alone that the probability of the defendant being guilty is 90% makes the prosecutors’s fallacy.

Consider the case of a lottery winner accused of cheating based on the improbability of winning. At the trial, the prosecutor calculates the (very small) probability of winning the lottery without cheating and argues that this is the chance of innocence. The logical flaw is that the prosecutor has failed to account for the large number of people who play the lottery.

read more »

Thought-terminating Cliché

A thought-terminating cliché is a commonly used phrase, sometimes passing as folk wisdom, used to propagate cognitive dissonance (discomfort caused by holding conflicting thoughts). Though the phrase in and of itself may be valid in certain contexts, its application as a means of dismissing dissent or justifying fallacious logic is what makes it thought-terminating.

The term was popularized by American psychiatrist Robert Jay Lifton in his 1956 book ‘Thought Reform and the Psychology of Totalism.’ Lifton said, ‘The language of the totalist environment is characterized by the thought-terminating cliché. The most far-reaching and complex of human problems are compressed into brief, highly reductive, definitive-sounding phrases, easily memorized and easily expressed. These become the start and finish of any ideological analysis.’

read more »

False Dilemma

A false dilemma (also called the fallacy of the false alternative, false dichotomy, the either-or fallacy, fallacy of the excluded middle, fallacy of false choice, black-and/or-white thinking, or the fallacy of exhaustive hypotheses) is a type of informal fallacy that involves a situation in which limited alternatives are considered, when in fact there is at least one additional option. The options may be a position that is between two extremes (such as when there are shades of grey) or may be completely different alternatives. The opposite of this fallacy is ‘argument to moderation.’

False dilemma can arise intentionally, when fallacy is used in an attempt to force a choice (such as, in some contexts, the assertion that ‘if you are not with us, you are against us’). But the fallacy can also arise simply by accidental omission of additional options rather than by deliberate deception.

read more »

Nirvana Fallacy

The nirvana fallacy is the informal fallacy of comparing actual things with unrealistic, idealized alternatives. It can also refer to the tendency to assume that there is a perfect solution to a particular problem. A closely related concept is the perfect solution fallacy.

By creating a false dichotomy that presents one option which is obviously advantageous—while at the same time being completely implausible—a person using the nirvana fallacy can attack any opposing idea because it is imperfect. The choice is not between real world solutions and utopia; it is, rather, a choice between one realistic possibility and another which is merely better.

read more »

Moralistic Fallacy

The moralistic fallacy is in essence the reverse of the naturalistic fallacy (defining the term ‘good’ in terms of one or more natural properties). The moralistic fallacy is the formal fallacy of assuming that what is desirable is found or inherent in nature. It presumes that what ought to be—something deemed preferable—corresponds with what is or what naturally occurs. What should be moral is assumed a priori to also be naturally occurring.

Cognitive scientist Steven Pinker writes that ‘The naturalistic fallacy is the idea that what is found in nature is good. It was the basis for Social Darwinism, the belief that helping the poor and sick would get in the way of evolution, which depends on the survival of the fittest. Today, biologists denounce the Naturalistic Fallacy because they want to describe the natural world honestly, without people deriving morals about how we ought to behave — as in: If birds and beasts engage in adultery, infanticide, cannibalism, it must be OK.’

read more »

Naturalistic Fallacy

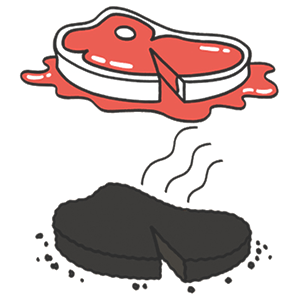

The phrase ‘naturalistic fallacy‘ refers to the claim that what is natural is inherently good or right, and that what is unnatural is bad or wrong (‘appeal to nature’). It is the converse of the ‘moralistic fallacy,’ the notion that what is good or right is natural and inherent. The naturalistic fallacy is related to (and even confused with) Hume’s ‘is–ought problem,’ which examines the difference between descriptive statements (about what is) and prescriptive or normative statements (about what ought to be).

Another usage of ‘naturalistic fallacy’ was described by British philosopher G. E. Moore in his 1903 book ‘Principia Ethica.’ Moore stated that a naturalistic fallacy is committed whenever a philosopher attempts to prove a claim about ethics by appealing to a definition of the term ‘good’ in terms of one or more natural properties (such as ‘pleasant,’ ‘more evolved,’ ‘desired,’ etc.).

read more »

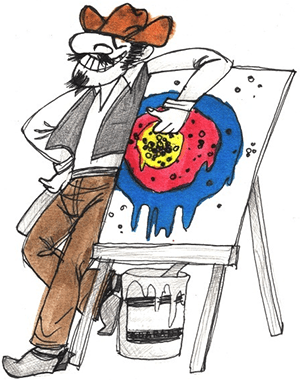

Texas Sharpshooter Fallacy

The Texas sharpshooter fallacy is a logical fallacy in which information that has no relationship is interpreted or manipulated until it appears to have meaning. The name comes from a joke about a Texan who fires some shots at the side of a barn, then paints a target centered on the biggest cluster of hits and claims to be a sharpshooter.

The fallacy does not apply if one had a prior expectation of the particular relationship in question before examining the data. It is related to the clustering illusion, which refers to the tendency in human cognition to interpret patterns in randomness where none actually exist.

read more »

Red Herring

A red herring is a literary tactic of diverting attention away from an item of significance. For example, in mystery fiction, where the identity of a criminal is being sought, an innocent party may be purposefully cast in a guilty light by the author through the employment of false emphasis, deceptive clues, ‘loaded’ words, or other descriptive tricks of the trade. The reader’s suspicions are thus misdirected, allowing the true culprit to go (temporarily at least) undetected. A false protagonist is another example of a red herring.

In a literal sense, there is no such fish species as a ‘red herring’; rather it refers to a particularly ‘strong kipper’ (a fish that has been strongly cured and smoked making it pungent smelling and reddish in color).

read more »

Straw Man

A straw man argument is an informal fallacy based on misrepresentation of an opponent’s position. To ‘attack a straw man’ is to create the illusion of having refuted a proposition by substituting it with a superficially similar yet not equivalent proposition (the ‘straw man’), and refuting it, without ever having actually refuted the original position.

The origins of the term are unclear; one common (folk) etymology given is that it originated with men who stood outside courthouses with a straw in their shoe in order to indicate their willingness to be a false witness, but the practice is of questionable authority. Another more popular origin is a human figure made of straw, such as practice dummies used in military training. Such a dummy is supposed to represent the enemy, but it is considerably easier to attack because it neither moves, nor fights back.

Parable of the Broken Window

The parable of the broken window was introduced by French economist and political theorist Frédéric Bastiat in his 1850 essay Ce qu’on voit et ce qu’on ne voit pas (That Which Is Seen and That Which Is Unseen) to illustrate the hidden costs associated with destroying property of others. The parable, also known as the broken window fallacy, demonstrates how the law of unintended consequences affects economic activity people typically see as beneficial.

read more »