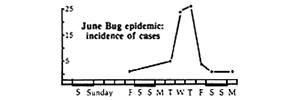

Hysterical contagion occurs when a group of people show signs of a physical problem or illness, when in reality there are psychological and social forces at work. It is a strong form of social contagion, which describes the copycat effect of imitative behavior based on the power of suggestion and word of mouth influence, because the symptoms often include those associated with clinical hysteria. The June bug epidemic serves as a classic example of hysterical contagion. In 1962 a mysterious disease broke out in a dressmaking department of a US textile factory. The symptoms included numbness, nausea, dizziness, and vomiting. Word of a bug in the factory that would bite its victims and develop the above symptoms quickly spread.

Soon sixty two employees developed this mysterious illness, some of whom were hospitalized. The news media reported on the case. After research by company physicians and experts from the US Public Health Service Communicable Disease Center, it was concluded that the case was one of mass hysteria. While the researchers believed some workers were bitten by the bug, anxiety was likely the cause of the symptoms. No evidence was ever found for a bug which could cause the above flu-like symptoms, nor did all workers demonstrate bites. Workers concluded that the environment was quite stressful; the plant had recently opened, was quite busy and organization was poor. Further, most of the victims reported high levels of stress in their lives. Social forces seemed at work too.

Hysterical Contagion

Deviancy Amplification Spiral

Deviancy amplification spiral is a media hype phenomenon defined by media critics as a cycle of increasing numbers of reports on a category of antisocial behavior or some other ‘undesirable’ event, leading to a moral panic. The term was coined in 1972 by Stanley Cohen in his book, ‘Folk Devils and Moral Panics.’ According to Cohen the spiral starts with some ‘deviant’ act. Usually the deviance is criminal, but it can also involve lawful acts considered morally repugnant by a large segment of society.

With the new focus on the issue, hidden or borderline examples that would not themselves have been newsworthy are reported, confirming the ‘pattern.’ Reported cases of such ‘deviance’ are often presented as just ‘the ones we know about’ or the ‘tip of the iceberg,’ an assertion that is nearly impossible to disprove immediately. For a variety of reasons, the less sensational aspects of the spiraling story that would help the public keep a rational perspective (such as statistics showing that the behavior or event is actually less common or less harmful than generally believed) tends to be ignored by the press.

read more »

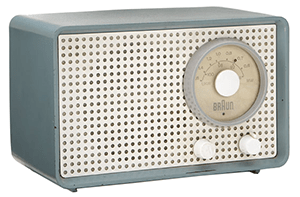

Dieter Rams

Dieter Rams (b. 1932) is a German industrial designer closely associated with the consumer products company Braun and the Functionalist school of industrial design. Rams studied architecture at the Werkkunstschule Wiesbaden as well as learning carpentry from 1943 to 1957. After working for the architect Otto Apel between 1953 and 1955 he joined the electronic devices manufacturer Braun where he became chief of design in 1961, a position he kept until 1995.

Rams once explained his design approach in the phrase ‘Weniger, aber besser’ which freely translates as ‘Less, but better.’ Rams and his staff designed many memorable products for Braun including the famous SK-4 record player and the high-quality ‘D’-series (D45, D46) of 35 mm film slide projectors. He is also known for designing the 606 Universal Shelving System by Vitsœ in 1960. Many of his designs — coffee makers, calculators, radios, audio/visual equipment, consumer appliances and office products — have found a permanent home at many museums over the world, including MoMA in New York. He continues to be highly regarded in design circles and currently has a major retrospective of his work on tour around the world.

read more »

Development Hell

In the jargon of the media-industry, ‘development hell‘ is a period during which a film or other project is trapped in development. A film, television program screenplay, computer program, concept, or idea stranded in development hell takes an especially long time to start production, or never does.

The film industry buys rights to many popular novels, video games, and comics, but it may take years for such properties to be successfully brought to the cinema, and often with considerable changes to the plot, characters, and general tone.

read more »

Dystopia

A dystopia [dis-toh-pee-uh] is the idea of a society in a repressive and controlled state, often under the guise of being utopian, as characterized in books like ‘Brave New World’ and ‘Nineteen Eighty-Four.’

Dystopian societies feature different kinds of repressive social control systems, various forms of active and passive coercion. Ideas and works about dystopian societies often explore the concept of humans abusing technology and humans individually and collectively coping, or not being able to properly cope with technology that has progressed far more rapidly than humanity’s spiritual evolution. Dystopian societies are often imagined as police states, with unlimited power over the citizens.

read more »

Fahrenheit 451

Fahrenheit 451 is a 1953 dystopian novel by Ray Bradbury. The novel presents a future American society where reading is outlawed and firemen start fires to burn books. Written in the early years of the Cold War, the novel is a critique of what Bradbury saw as issues in American society of the era. In 1947, Bradbury wrote a short story titled ‘Bright Phoenix’ (later revised for publication in a 1963 issue of ‘The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction’). Bradbury expanded the basic premise of “Bright Phoenix” into ‘The Fireman,’ a novella published in a 1951 issue of ‘Galaxy Science Fiction.’ First published in 1953 by Ballantine Books, Fahrenheit 451 is twice as long as ‘The Fireman.’ A few months later, the novel was serialized in the March, April, and May 1954 issues of Playboy. Bradbury wrote the entire novel on a pay typewriter in the basement of UCLA’s Powell Library.

The novel has been the subject of various interpretations, primarily focusing on the historical role of book burning in suppressing dissenting ideas. Bradbury has stated that the novel is not about censorship, but a story about how television destroys interest in reading literature, which leads to a perception of knowledge as being composed of factoids, partial information devoid of context.

read more »

Nineteen Eighty-Four

Nineteen Eighty-Four (first published in 1949) by George Orwell is a dystopian novel about Oceania, a society ruled by the oligarchical dictatorship of the Party. Life in the Oceanian province of Airstrip One is a world of perpetual war, pervasive government surveillance, and incessant public mind control, accomplished with a political system euphemistically named English Socialism (Ingsoc), which is administrated by a privileged Inner Party elite. Yet they too are subordinated to the totalitarian cult of personality of Big Brother, the deified Party leader who rules with a philosophy that decries individuality and reason as thoughtcrimes; thus the people of Oceania are subordinated to a supposed collective greater good.

The protagonist, Winston Smith, is a member of the Outer Party who works for the Ministry of Truth (Minitrue), which is responsible for propaganda and historical revisionism. His job is to re-write past newspaper articles so that the historical record is congruent with the current party ideology. Because of the childhood trauma of the destruction of his family — the disappearances of his parents and sister — Winston Smith secretly hates the Party, and dreams of rebellion against Big Brother.

read more »

We

‘We‘ is a dystopian novel by Yevgeny Zamyatin completed in 1921. It was written in response to the author’s personal experiences during the Russian revolution of 1905, the Russian revolution of 1917, his life in the Newcastle suburb of Jesmond, and his work in the Tyne shipyards during the First World War. It was on Tyneside that he observed the rationalization of labor on a large scale. Zamyatin was a trained marine engineer, hence his dispatch to Newcastle to oversee ice-breaker construction for the Imperial Russian navy. The novel was first published in 1924 by E.P. Dutton in New York in an English translation.

‘We’ is set in the future. D-503 lives in the One State, an urban nation constructed almost entirely of glass, which allows the secret police/spies to inform on and supervise the public more easily. The structure of the state is analogous to the prison design concept developed by Jeremy Bentham commonly referred to as the Panopticon. Furthermore, life is organized to promote maximum productive efficiency along the lines of the system advocated by the hugely influential F.W. Taylor. People march in step with each other and wear identical clothing. There is no way of referring to people save by their given numbers. Males have odd numbers prefixed by consonants, females have even numbers prefixed by vowels.

read more »

Brave New World

Brave New World is Aldous Huxley’s fifth novel, written in 1931 and published in 1932. Set in London of CE 2540 (632 A.F. in the book), the novel anticipates developments in reproductive technology and sleep-learning that combine to change society.

The future society is an embodiment of the ideals that form the basis of futurology (the study of postulating possible futures). Huxley answered this book with a reassessment in an essay, ‘Brave New World Revisited (1958),’ and with his final work, a novel titled ‘Island’ (1962), a utopian counterpart to ‘Brave New World’s dystopian setting.

read more »

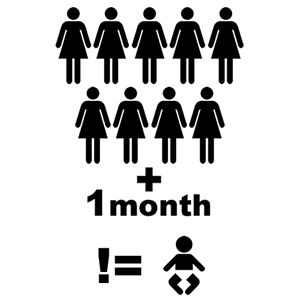

The Mythical Man-Month

‘The Mythical Man-Month: Essays on Software Engineering’ is a book on software engineering and project management by Fred Brooks, whose central theme is that ‘adding manpower to a late software project makes it later.’ This idea is known as Brooks’ law, and is presented along with the second-system effect (the tendency of small, elegant, and successful systems to have elephantine, feature-laden monstrosities as their successors) and advocacy of prototyping.

Brooks’ observations are based on his experiences at IBM while managing the development of OS/360. He had mistakenly added more workers to a project falling behind schedule. He also made the mistake of asserting that one project — writing an Algol compiler — would require six months, regardless of the number of workers involved (it required longer). The tendency for managers to repeat such errors in project development led Brooks to quip that his book is called ‘The Bible of Software Engineering,’ because ‘everybody quotes it, some people read it, and a few people go by it.’ The book is widely regarded as a classic on the human elements of software engineering. The work was first published in 1975

read more »

Overengineering

Overengineering is when a product is more robust or complicated than necessary for its application, either (charitably) to ensure sufficient factor of safety, sufficient functionality, or due to design errors.

Overengineering is desirable when safety or performance on a particular criterion is critical, or when extremely broad functionality is required, but it is generally criticized from the point of view of value engineering as wasteful. As a design philosophy, such overcomplexity is the opposite of the minimalist school of thought.

read more »

Bloatware

Software bloat is a process whereby successive versions of a computer program include an increasing proportion of unnecessary features that are not used by end users, or generally use more system resources than necessary, while offering little or no benefit to its users.

Software developers in the 1970s had severe limitations on disk space and memory. Every byte and clock cycle counted, and much work went into fitting the programs into available resources. Achieving this efficiency was one of the highest values of computer programmers, and the best programs were often called ‘elegant’; —seen as a form of high art.

read more »