In the philosophy of science, the pessimistic induction is an argument which seeks to rebut scientific realism, the belief that we have good reasons to believe that our presently successful scientific theories are true or approximately true, where approximate truth means a theory is able to make novel predictions.

Pessimistic induction undermines the realist’s warrant for his epistemic optimism via historical counterexample. Using meta-induction, philosopher of science Larry Laudan argues that if past scientific theories which were successful were found to be false, we have no reason to believe the realist’s claim that our currently successful theories are approximately true. The argument was first fully postulated by Laudan in 1981.

read more »

Pessimistic Induction

Factual Relativism

Factual relativism or epistemic relativism is a mode of reasoning which extends relativism and subjectivism to factual matter and reason. In factual relativism the facts used to establish the truth or falsehood of any statement are understood to be relative to the perspective of those proving or falsifying the proposition. Factual relativism is contested by factual universalism.

One school of thought compares scientific knowledge to the mythology of other cultures, arguing that it is merely our society’s set of myths based on our society’s assumptions. For support, Austrian-American philosopher of science Paul Feyerabend’s comments in ‘Against Method’ that, The similarities between science and myth are indeed astonishing’ and ‘First-world science is one science among many’ are sometimes cited, although it is not clear if Feyerabend meant them entirely seriously.

read more »

Pathological Science

Pathological science is the process by which ‘people are tricked into false results … by subjective effects, wishful thinking or threshold interactions.’ The term was first used by Irving Langmuir, Nobel Prize-winning chemist, during a 1953 colloquium at the Knolls Research Laboratory. Langmuir said a pathological science is an area of research that simply will not ‘go away’—long after it was given up on as ‘false’ by the majority of scientists in the field. He called pathological science ‘the science of things that aren’t so.’

Sociologist Bart Simon lists it among practices pretending to be science: ‘categories [.. such as ..] pseudoscience, amateur science, deviant or fraudulent science, bad science, junk science, and popular science [..] pathological science, cargo-cult science, and voodoo science ..’ Examples of pathological science may include homeopathy, Martian canals, N-rays, polywater, water memory (homeopathy), perpetual motion, and cold fusion. The theories and conclusions behind all of these examples are currently rejected or disregarded by the majority of scientists.

read more »

Cargo Cult Science

Cargo cult science refers to practices that have the semblance of being scientific, but do not in fact follow the scientific method. The term was first used by the physicist Richard Feynman during his commencement address at the California Institute of Technology in 1974. The speech is reproduced in the book ‘Surely You’re Joking, Mr. Feynman!’ He based the phrase on a concept in anthropology, the cargo cult, which describes how some pre-scientific cultures interpreted technologically advanced visitors as religious or supernatural figures who brought boons of cargo.

Later, in an effort to call for a second visit the natives would develop and engage in complex religious rituals, mirroring the previously observed behavior of the visitors manipulating mock machines but without understanding the true nature of those tasks. Just as cargo cultists create mock airports that fail to produce airplanes, cargo cult scientists conduct flawed research that superficially resembles the scientific method, but which fails to produce scientifically useful results.

read more »

Social Darwinism

Social Darwinism is an ideology of society that seeks to apply biological concepts of Darwinism or of evolutionary theory to sociology and politics, often with the assumption that conflict between groups in society leads to social progress as superior groups outcompete inferior ones.

It is a modern name given to the various theories of society that emerged in England and the United States in the 1870s, which, it is alleged, sought to apply biological concepts to sociology and politics. The term social Darwinism gained widespread currency when used in 1944 to oppose these earlier concepts.

read more »

Strong Programme

The strong programme or Strong Sociology is a variety of the sociology of scientific knowledge (SSK) particularly associated with David Bloor, Barry Barnes, Harry Collins, Donald A. MacKenzie, and John Henry. SSK is the study of science as a social activity, especially dealing with ‘the social conditions and effects of science, and with the social structures and processes of scientific activity.’

The strong programme’s influence on Science and Technology Studies (the study of how social, political, and cultural values affect scientific research and technological innovation, and how these, in turn, affect society, politics and culture) is credited as being unparalleled. The largely Edinburgh-based school of thought has illustrated how the existence of a scientific community, bound together by allegiance to a shared paradigm, is a pre-requisite for normal scientific activity.

read more »

Science for the People

Science for the People is a left-wing organization that emerged from the antiwar culture of the United States in the 1970s. A similar organization of the same name was founded in 2002.

The original group was composed of professors, students, and other concerned citizens who sought to end potential oppression brought on by pseudoscience, or by what it considered the misuse of science. ‘Science for the People’ generated much controversy in the 1970s for the radical tactics of some of its members.

read more »

Science Studies

Science studies is an interdisciplinary research area that seeks to situate scientific expertise in a broad social, historical, and philosophical context. It is concerned with the history of scientific disciplines, the interrelationships between science and society, and the alleged covert purposes that underlie scientific claims. While it is critical of science, it holds out the possibility of broader public participation in science policy issues.

The word ‘science’ is used in the sense of natural, social and formal sciences – areas of research that tend toward positivism (‘all true knowledge is scientific’). The word ‘science’ thus explicitly excludes the humanities and cultural studies, which tend toward relativism (‘the truth of a statement is based on conditions’). Thus, while the topic of research in ‘science studies’ is the sciences, the main approaches to research come from the humanities (e.g. history) (hence the word ‘study’ in the title, rather than for example ‘theory’). Science studies scholars study (investigate) specific phenomena such as technological milieus, laboratory culture, science policy, and the role of the university.

read more »

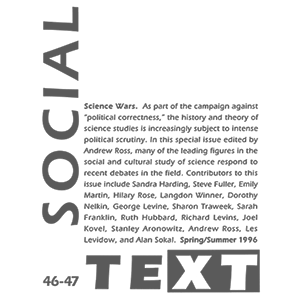

Science Wars

The science wars were a series of intellectual exchanges, between scientific realists and postmodernist critics, about the nature of scientific theory which took place principally in the United States in the 1990s. The postmodernists questioned scientific objectivity, and critiqued the scientific method and scientific knowledge in cultural studies, cultural anthropology, feminist studies, comparative literature, media studies, and science and technology studies. The scientific realists countered that objective scientific knowledge is real, and accused postmodernist critics of having little understanding of the science they were criticizing.

Until the mid-20th century, the philosophy of science had concentrated on the viability of scientific method and knowledge, proposing justifications for the truth of scientific theories and observations and attempting to discover on a philosophical level why science worked. Already Karl Popper had begun to attack this view. Popper denied outright that justification existed for such concepts as truth, probability or even belief in scientific theories, thereby laying fertile foundations for the growth of postmodernist attitudes.

read more »

Fashionable Nonsense

‘Fashionable Nonsense: Postmodern Intellectuals’ Abuse of Science’ (French: ‘Impostures Intellectuelles’) is a 1997 book by NYU physics professor Alan Sokal and Belgian theoretical physicist Jean Bricmont. Sokal is best known for the Sokal Affair, in which he submitted a deliberately absurd article to ‘Social Text,’ a critical theory journal, and was able to get it published. The English editions were revised for greater relevance to debates in the English-speaking world.

As part of the so-called ‘science wars’ (a series of intellectual exchanges, between scientific realists and postmodernist critics), the book criticizes postmodernism in academia for what it claims are misuses of scientific and mathematical concepts in postmodern writing. According to some reports, the response within the humanities was ‘polarized.’ Critics of Sokal and Bricmont charge that they lack understanding of the writing they were criticizing. Responses from the scientific community were more supportive.

read more »