Linking R and intrusive R are sandhi phenomena (when the form of a word changes as a result of its position in an utterance) wherein a rhotic consonant (r-like sound) is pronounced between two consecutive vowels with the purpose of avoiding a hiatus, that would otherwise occur in the expressions, such as ‘tuner amp,’ although in isolation ‘tuner’ is pronounced the same as ‘tuna’ in non-rhotic varieties of English (those that skip some r sounds).

These phenomena occur in many of these dialects, such as those in most of England and Wales, parts of the United States, and all of the Anglophone societies of the southern hemisphere, with the exception of South Africa. In these varieties, /r/ is pronounced only when it is immediately followed by a vowel.

By definition, non-rhotic varieties of English pronounce /r/ only when it immediately precedes a vowel. This is called r-vocalisation, r-loss, r-deletion, r-dropping, r-lessness, or non-rhoticity. In contrast, speakers of rhotic dialects, such as those of Scotland, Ireland, and most of North America (except in some of the Northeastern United States and Southern United States), always pronounce an /r/ in ‘tuner’ and never in ‘tuna’ so that the two always sound distinct, even when pronounced in isolation. Hints of non-rhoticity go back as early as the 15th century, and the feature was common (at least in London) by the early 18th century.In many non-rhotic accents, words historically ending in /r/ may be pronounced with /r/ when they are closely followed by another morpheme beginning with a vowel sound. Here, ‘closely’ means the following word must be in the same prosodic unit (that is, not separated by a pausa). This phenomenon is known as linking R. Not all non-rhotic accents feature linking R. South African English, African-American Vernacular English and non-rhotic varieties of Southern American English are notable for not using a linking R.

The phenomenon of intrusive R is a reinterpretation of linking R into an r-insertion rule that affects any word that ends in the non-high vowels (vowels pronounced with the tongue not raised high in the mouth) when such a word is closely followed by another word beginning in a vowel sound. An /r/ is inserted between them even when no final /r/ was historically present. The epenthetic /r/ can be inserted to prevent hiatus (two consecutive vowel sounds).

In extreme cases, an intrusive R can follow a reduced schwa (unstressed central vowel), such as by English speakers from Eastern Massachusetts. Other recognizable examples are the Beatles singing: ‘I saw-r-a film today, oh boy’ in the song ‘A Day in the Life,’ from their 1967 album ‘Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band’; in the song ‘Champagne Supernova’ by Oasis: ‘supernova-r-in the sky’; in the song ‘Scenes from an Italian Restaurant’ by Billy Joel: ‘Brenda-r-and Eddie’; in the phrases, ‘law-r-and order’ and ‘Victoria-r-and Albert Museum,’ and even in the name ‘Maya-r-Angelou.’

This is now common enough in parts of England that, by 1997, the linguist John C. Wells considered it objectively part of Received Pronunciation, though he noted that ‘the speech conscious often dislike it and disapprove of it.’ It is or was stigmatized as an incorrect pronunciation in some other standardized non-rhotic accents, too.

Just as with linking R, intrusive R may also occur between a root morpheme and certain suffixes, such as ‘draw(r)ing,’ ‘withdraw(r)al,’ or ‘Kafka(r)esque.’

A rhotic speaker may use alternative strategies to prevent the hiatus, such as the insertion of a glottal stop (a consonant formed by the audible release of the airstream after complete closure of the glottis) to clarify the boundary between the two words. Varieties that feature linking R but not intrusive R show a clear phonemic distinction between words with and without /r/ in the syllable coda, the consonant or consonant cluster that follows the nucleus (the vowel) of a syllable.

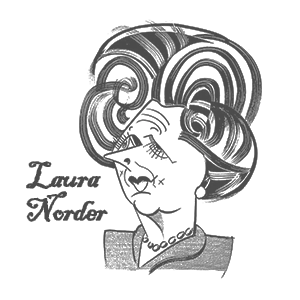

Margaret Thatcher was nicknamed “Laura Norder” because of her references during her period of office to “law and order” with an intrusive /r/.

A 2006 study at the University of Bergen examined the pronunciation of 30 British newsreaders on nationally broadcast newscasts around the turn of the 21st century speaking. It was found that all the newsreaders used some linking R and 90% (27 of 30) used some intrusive R.

Overall, linking R was used in 59.8% of possible sites and intrusive R was used in 32.6% of possible sites. The factors influencing the use of both linking and intrusive R were found to be the same. Factors favouring the use of R-sandhi included adjacency to short words, adjacency to grammatical or otherwise non-lexical words, and informal style (interview rather than prepared script). Factors disfavouring the use of R-sandhi included adjacency to proper names; occurrence immediately before a stressed syllable; the presence of another /r/ in the vicinity; and more formal style (prepared script rather than interview).

The following factors were proposed as accounting for the difference between the frequency of linking and intrusive R: overt stigmatization of intrusive R; the speakers being professional newsreaders and thus, presumably, speech-conscious professionals; the speakers (in most cases) reading from a written script, making the orthographic distinction between linking and intrusive R extremely salient; and the disparity between the large number of short grammatical words that end in possible linking R (e.g. “for”, “or”, “are”, etc.) and the absence of such words that end in possible intrusive R.

The Daily Omnivore

Everything is Interesting