The OP-1 is a synthesizer, sampler, and sequencer designed and manufactured by the Stockholm-based company Teenage Engineering. The OP-1 is Teenage Engineering’s first product; it was released in 2011. The OP-1 is well known for its unconventional design, OLED display, and eight synthesizer engines. It has received some criticism for its physical limitations; however, according to Teenage Engineering cofounder Jesper Kouthoofd, these limitations were programmed into the synthesizer in order to stimulate the design process and the creativity of the user.

The design of the OP-1 was influenced by the VL-Tone, a synthesizer and pocket calculator manufactured by Casio in 1980 that is known for its toy-like novelty sounds and cheap build quality, as well as its inorganic design. In an interview with Damian Kulash of OK Go, Kouthoofd explained that he worked in a music store when he was young, and he was inspired by Japanese synthesizers of the 1980s. He has also stated that ‘limitations are OP-1’s biggest feature.’ The synthesizer’s designers attempted to use the limitation of physical hardware to encourage the unit to stimulate creativity, which might become unfocused in a limitless environment, such as a digital audio workstation.

OP-1

Yayoi Kusama

Yayoi [yah-yoy] Kusama [koo-sah-muh] (b. 1929) is a Japanese artist whose paintings, collages, soft sculptures, performance art and environmental installations all share an obsession with repetition, pattern, and accumulation (she has described herself as an ‘obsessive artist’). Kusama’s work is based in Conceptual art (in which the concepts or ideas involved in the work take precedence over traditional aesthetic and material concerns) and shows some attributes of feminism, minimalism, surrealism, Art Brut, pop art, and abstract expressionism, and is infused with autobiographical, psychological, and sexual content.

Kusama is also a published novelist and poet, and has created notable work in film and fashion design. She has long struggled with mental illness, and has experienced hallucinations and severe obsessive thoughts since childhood, often of a suicidal nature. She claims that as a small child she suffered physical abuse by her mother. In 2008, a work by her sold for $5.1 million, a record for a living female artist.

read more »

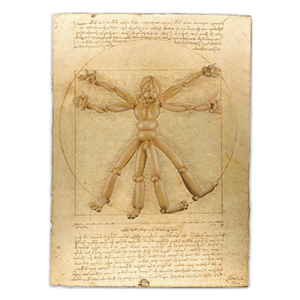

Balloon Modelling

Balloon modelling is the shaping of special modelling balloons into almost any given shape, often a balloon animal. People who create balloon animals and other twisted balloon sculptures are called Twisters, Balloon Benders and Balloon Artists. Twisters often perform in restaurants, at birthday parties, fairs and at public and private events or functions. Two of the primary design styles are single balloon modelling, which restricts itself to the use of one balloon per model, and multiple balloon modelling, which uses more than one balloon.

Each style has its own set of challenges and skills, but few twisters who have reached an intermediate or advanced skill level limit themselves to one style or another. Depending on the needs of the moment, they might easily move between the one-balloon or multiple approaches, or they might even incorporate additional techniques such as ‘weaving’ and ‘stuffing.’ Modelling techniques have evolved to include a range of very complex moves, and a highly specialized vocabulary has emerged to describe the techniques involved and their resulting creations.

I Can’t Go for That (No Can Do)

‘I Can’t Go for That (No Can Do)‘ is a 1981 song recorded by Daryl Hall and John Oates. It was the fourth number-one hit single of their career and second hit single from their album ‘Private Eyes.’ It features Charles DeChant on saxello. Daryl Hall sketched out the basic song one evening at a music studio in New York City in 1981 after a recording session for the ‘Private Eyes’ album. Hall began to play a bass line on a Korg organ, and sound engineer Neil Kernon recorded the result. Hall then came up with a guitar riff, which he and Oates worked on together. The next day, Hall and Sara Allen worked on the lyrics.

Thanks to heavy airplay on urban contemporary radio stations, it topped the U.S. R&B chart, a rare feat for a non-African American act. According to the Hall and Oates biography, Hall, upon learning that it had gone to number one wrote in his diary, ‘I’m the head soul brother in the U.S. Where to now?’ Also according to Hall, during the recording of ‘We Are the World,’ Jackson approached him and admitted to lifting the bass line for ‘Billie Jean’ from ‘I Can’t Go For That (No Can Do).’ Hall says that he told Jackson that he had lifted the bass line from another song himself, and that it was ‘something we all do.’

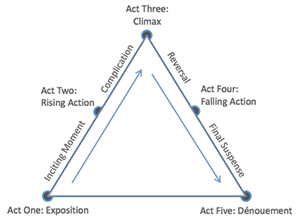

Jo-ha-kyū

Jo-ha-kyū is a concept of modulation and movement applied in a wide variety of traditional Japanese arts. Roughly translated to ‘beginning, break, rapid,’ it essentially means that all actions or efforts should begin slowly, speed up, and then end swiftly. This concept is applied to elements of the Japanese tea ceremony, kendō and other martial arts, dramatic structure in Japanese theater and film, and traditional collaborative linked verse forms. The concept originated in court music, specifically in the ways in which elements of the music could be distinguished and described. Though eventually incorporated into a number of disciplines, it was most famously adapted, and thoroughly analyzed and discussed by the great playwright Zeami, who viewed it as a universal concept applying to the patterns of movement of all things.

Zeami described the first act as ‘Love’; the play opens auspiciously, using gentle themes and pleasant music to draw in the attention of the audience. The second act is described as ‘Warriors and Battles.’ Though it need not contain actual battle, it is generally typified by heightened tempo and intensity of plot. The third act, the climax of the entire play, is typified by pathos and tragedy. The plot achieves its dramatic climax. The fourth is a michiyuki (journey), which eases out of the intense drama of the climactic act, and often consists primarily of song and dance rather than dialogue and plot. The fifth act, then, is a rapid conclusion. All loose ends are tied up, and the play returns to an auspicious setting.

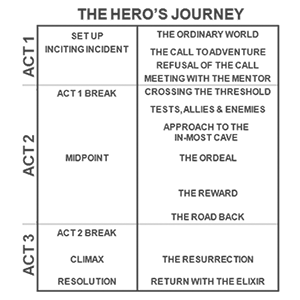

Three-act Structure

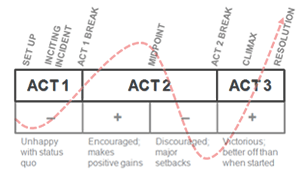

The Three-Act Structure is a model used in writing and evaluating modern storytelling which divides a screenplay into a three parts called the ‘Setup,’ ‘Confrontation,’ and ‘Resolution.’ The first act is used to establish the main characters, their relationships and the normal world they live in.

Early in the first act, a dynamic, on-screen incident occurs to the main character (the protagonist), whose response leads to a second and more dramatic situation, known as the first ‘turning point,’ which (a) signals the end of the first act, (b) ensures life will never be the same again for the protagonist, and (c) raises a dramatic question that will be answered in the climax of the film.

read more »

Act Structure

Act structure explains how a plot of a film story is composed. Just like plays (Staged drama) have ‘Acts,’ critics and screenwriters tend to divide films into acts; though films don’t require to be physically broken down as such in reality.

Whereas plays are actual performances that need ‘breaks’ in the middle for change of set, costume, or for the artists’ rest; films are recorded performances shown mechanically and therefore don’t need actual breaks. Still they are divided into acts for reasons that are in aesthetic and structural conformation with the original idea of Act in theater.

read more »

Dramatic Structure

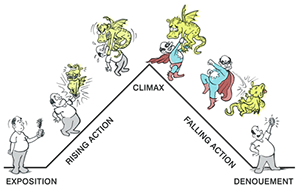

Dramatic structure is the structure of a dramatic work such as a play or film. Many scholars have analyzed dramatic structure, beginning with Aristotle in his ‘Poetics’ (c. 335 BCE). In ‘Poetics,’ Aristotle put forth the idea that ‘A whole is what has a beginning and middle and end.’ This three-part view of a plot structure (with a beginning, middle, and end – technically, the protasis, epitasis, and catastrophe) prevailed until the Roman drama critic Horace advocated a 5-act structure in his ‘Ars Poetica.’ After falling into disuse, renaissance dramatists revived the use of the 5-act structure.

Gustav Freytag’s analysis of ancient Greek and Shakespearean drama is canonical. Although Freytag’s description of dramatic structure is based on five-act plays, it can be applied (sometimes in a modified manner) to short stories and novels as well. Nonetheless it does not always translate well, especially in modern plays such as Alfred Uhry’s ‘Driving Miss Daisy,’ which is actually divided into 25 scenes without concrete acts.

read more »

Information Dump

When the presentation of information in fiction becomes wordy, it is sometimes referred to as an ‘information dump.’ It is expressed by characters in dialogue or monologue and sometimes referred to as ‘idiot lectures.’ They are sometimes placed at the beginning of stories as a means of establishing the premise of the plot.

They also appear in science fiction, but it is considered poor writing when characters explain things to each other that they would already know. For example, if you need to call someone, you don’t stop to explain to a colleague that you are now going to use a device controlled with digital circuits to use radio waves to transmit your voice. Why? Because your contemporaries already know how cellular radio telephones work.

read more »

Show, Don’t Tell

Show, don’t tell is an admonition to fiction writers to write in a manner that allows the reader to experience the story through a character’s action, words, thoughts, senses, and feelings rather than through the narrator’s exposition, summarization, and description. The advice is not to be heavy-handed, or to drown the reader in adjectives, but to allow issues to emerge from the text instead.

The advice applies equally to fiction and nonfiction, but the approach should not be applied to all incidents in the story. According to author James Scott Bell, ‘Sometimes a writer tells as a shortcut, to move quickly to the meaty part of the story or scene. Showing is essentially about making scenes vivid. If you try to do it constantly, the parts that are supposed to stand out won’t, and your readers will get exhausted.’

read more »

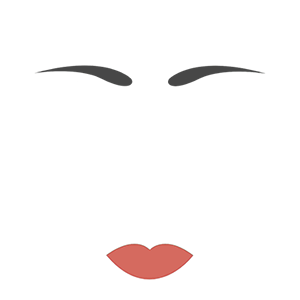

Ubiquitous Gaze

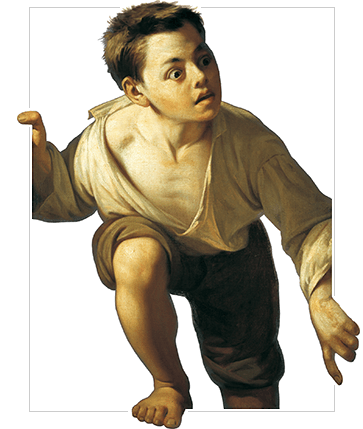

Ubiquitous [yoo-bik-wi-tuhs] gaze, also referred to as pursuing eyes, is an art term for the effect created by certain portraits, such as the ‘Mona Lisa,’ which give the impression that the subject’s eyes are following the viewer.

When such a painting is viewed from any angle, the subject’s eyes still appear to be looking straight into the viewer’s. This is an effect of perspective and may be deliberate or not. Ubiquitous gaze is a common technique of the trompe-l’œil school of painting, and can be seen in numerous works.

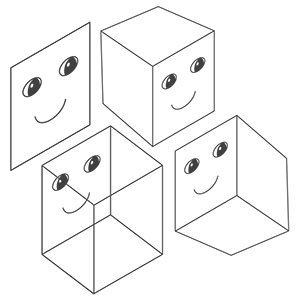

Trompe L’oeil

Trompe l’oeil [trawmp loy], French for ‘deceive the eye’, is an art technique involving extremely realistic imagery in order to create the optical illusion that the depicted objects appear in three dimensions. Although the phrase has its origin in the Baroque period, when it refers to perspectival illusionism, use of trompe-l’œil dates back much further. It was (and is) often employed in murals. Instances from Greek and Roman times are known, for instance in Pompeii. A typical trompe-l’œil mural might depict a window, door, or hallway, intended to suggest a larger room.

A version of an oft-told ancient Greek story concerns a contest between two renowned painters. Zeuxis (born around 464 BCE) produced a still life painting so convincing, that birds flew down from the sky to peck at the painted grapes. He then asked his rival, Parrhasius, to pull back a pair of very tattered curtains in order to judge the painting behind them. Parrhasius won the contest, as his painting was of the curtains themselves.

read more »