Ordinary language philosophy came out of followers of the later work of Ludwig Wittgenstein at the University of Oxford, and was most popular between 1930 and 1970. It is a philosophical school that approaches traditional philosophical problems as rooted in misunderstandings philosophers develop by distorting or forgetting what words actually mean in everyday use.

This approach typically involves eschewing philosophical ‘theories’ in favor of close attention to the details of the use of everyday, ‘ordinary’ language. Sometimes called ‘Oxford philosophy,’ it is generally associated with the work of a number of mid-century Oxford professors: mainly J.L. Austin, but also Gilbert Ryle, H.L.A. Hart, and Peter Strawson. The later Ludwig Wittgenstein is ordinary language philosophy’s most celebrated proponent outside the Oxford circle. Second generation figures include Stanley Cavell and John Searle.

read more »

Ordinary Language Philosophy

Orange Catholic Bible

The Orange Catholic Bible (abbreviated to O. C. Bible or OCB) is a fictional book from the ‘Dune’ universe created by Frank Herbert. Created in the wake of the crusade against thinking machines known as the Butlerian Jihad, the Orange Catholic Bible is the key religious text in the Dune universe and is described thus in the glossary of the 1965 novel:

‘ORANGE CATHOLIC BIBLE: the ‘Accumulated Book,’ the religious text produced by the Commission of Ecumenical Translators. It contains elements of most ancient religions, including the Maometh Saari, Mahayana Christianity, Zensunni Catholicism, and Buddislamic traditions. Its supreme commandment is considered to be: ‘Thou shalt not disfigure the soul,’ followed by ‘Thou shalt not make a machine in the likeness of a human mind.’

read more »

Syncretism

Syncretism [sing-kri-tiz-uhm] is the combining of different (often contradictory) beliefs, often while melding practices of various schools of thought. Syncretism may involve the merger and analogizing of several originally discrete traditions, especially in the theology and mythology of religion, thus asserting an underlying unity and allowing for an inclusive approach to other faiths. Syncretism also occurs commonly in expressions of arts and culture (known as eclecticism) as well as politics (syncretic politics).

The word entered the English language in 1618; it derives from Latin ‘syncretismus,’ drawing on Greek (‘synkretismos’), meaning ‘Cretan federation.’ The Greek word occurs in Plutarch’s (1st century) essay on ‘Fraternal Love’ in his ‘Moralia.’ He cites the example of the Cretans, who compromised and reconciled their differences and came together in alliance when faced with external dangers. ‘And that is their so-called Syncretism.’

read more »

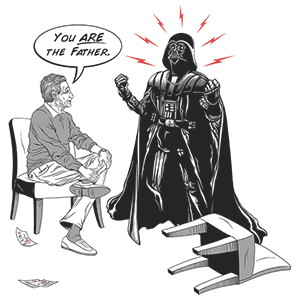

Anagnorisis

Anagnorisis [an-ag-nawr-uh-sis] is a moment in a play or other work when a character makes a critical discovery. Anagnorisis originally meant recognition in its Greek context, not only of a person but also of what that person stood for. It was the hero’s sudden awareness of a real situation, the realization of things as they stood, and finally, the hero’s insight into a relationship with an often antagonistic character in Aristotelian tragedy.

In the Aristotelian definition of tragedy, it was the discovery of one’s own identity or true character (e.g. Cordelia, Edgar, Edmund, etc. in Shakespeare’s ‘King Lear’) or of someone else’s identity or true nature (e.g. Lear’s children, Gloucester’s children) by the tragic hero. In his ‘Poetics,’ Aristotle defined anagnorisis as ‘a change from ignorance to knowledge, producing love or hate between the persons destined by the poet for good or bad fortune.’ Shakespeare did not base his works on Aristotelian theory of tragedy, including use of hamartia (an injury committed in ignorance), yet his tragic characters still commonly undergo anagnorisis as a result of their struggles.

read more »

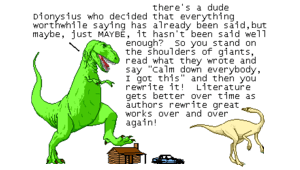

Dionysian Imitatio

Dionysian imitatio is the influential literary method of imitation as formulated by Greek author Dionysius of Halicarnassus in the first century BCE, which conceived it as the rhetoric practice of emulating, adapting, reworking and enriching a source text by an earlier author. It marked the beginning of the doctrine of imitation, which dominated the Western history of art up until 18th century, when the notion of romantic originality was introduced.

The imitation literary approach is closely linked with the widespread observation that ‘everything has been said already,’ which was also stated by Egyptian scribes around 2000 BCE. The ideal aim of this approach to literature was not originality, but to surpass the predecessor by improving their writings and set the bar to a higher level.

read more »

Omega Point

Omega Point is a term coined by the French Jesuit Pierre Teilhard de Chardin (1881–1955) to describe a maximum level of complexity and consciousness towards which he believed the universe was evolving.

In this theory, developed by Teilhard in ‘The Future of Man’ (1950), the universe is constantly developing towards higher levels of material complexity and consciousness, a theory of evolution that Teilhard called the Law of Complexity/Consciousness. For Teilhard, the universe can only move in the direction of more complexity and consciousness if it is being drawn by a supreme point of complexity and consciousness.

read more »

Competent Man

In literature, the competent man is a stock character who can do anything perfectly, or at least exhibits a very wide range of abilities and knowledge, making him a form of polymath. While not the first to use such a character type, the heroes (and heroines) of Robert A. Heinlein’s fiction are generally competent men/women (with Jubal Harshaw being a prime example), and one of Heinlein’s characters Lazarus Long gives a good summary of requirements: ‘A human being should be able to change a diaper, plan an invasion, butcher a hog, conn a ship, design a building, write a sonnet, balance accounts, build a wall, set a bone, comfort the dying, take orders, give orders, cooperate, act alone, solve equations, analyze a new problem, pitch manure, program a computer, cook a tasty meal, fight efficiently, die gallantly. Specialization is for insects.’

The competent man, more often than not, is written without explaining how he achieved his wide range of skills and abilities, especially as true expertise typically suggests practical experience instead of learning through books or formalized education alone. While not implausible with older or unusually long lived characters, when such characters are young it is often not adequately explained as to how they acquired so many skills at an early age. It would be easy for a reader to form the impression that the competent man is just basically a superior sort of human being. Many non-superpowered comic book characters are written as hyper-competent characters due to the perception that they would simply be considered underpowered otherwise.

Meat Analogue

A meat analogue, also called a meat substitute, mock meat, faux meat, or imitation meat, approximates the aesthetic qualities (primarily texture, flavor, and appearance) and/or chemical characteristics of specific types of meat. Many analogues are soy-based (e.g. tofu, tempeh). Generally, meat analogue is understood to mean a food made from non-meats, sometimes without other animal products such as dairy. The market for meat imitations includes vegetarians, vegans, and people following religious dietary laws, such as Kashrut or Halal. Hindu cuisine features the oldest known use of meat analogues. Meat analogue may also refer to a meat-based and/or less-expensive alternative to a particular meat product, such as surimi (a fish slurry used to make products such as imitation crab meat).

Some vegetarian meat analogues are based on centuries-old recipes for seitan (wheat gluten), rice, mushrooms, legumes, tempeh, or pressed-tofu, with flavoring added to make the finished product taste like chicken, beef, lamb, ham, sausage, seafood, etc. Yuba is another soy-based meat analogue, made by layering the thin skin which forms on top of boiled soy milk. Some more recent meat analogues include textured vegetable protein (TVP), which is a dry bulk commodity derived from soy, soy concentrate, mycoprotein-based Quorn which uses egg white as a binder making them unsuitable for vegans, and modified defatted peanut flour.

Unix Philosophy

The Unix philosophy [yoo-niks] is a set of cultural norms and philosophical approaches to developing software based on the experience of leading developers of the Unix operating system. Doug McIlroy, the inventor of Unix, summarized the philosophy as follows: ‘Write programs that do one thing and do it well.’ Additional credos include: ‘Write programs to work together. Write programs to handle text streams, because that is a universal interface.’

Richard P. Gabriel, an expert on the Lisp programming language, suggests that a key advantage of Unix was that it embodied a design philosophy he termed ‘worse is better,’ in which simplicity of both the interface and the implementation are more important than any other attributes of the system—including correctness, consistency, and completeness. Gabriel argues that this design style has key evolutionary advantages, though he questions the quality of some results.

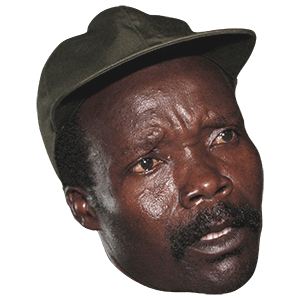

Joseph Kony

Joseph Kony (b.1964) is a Ugandan guerrilla group leader, head of the Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA), a group engaged in a violent campaign to establish theocratic government based on the Ten Commandments throughout Uganda. The LRA say that spirits have been sent to communicate this mission directly to Kony. Directed by Kony, the LRA have also spread to parts of the Democratic Republic of Congo and Sudan. It has abducted and forced an estimated 66,000 children to fight for them, and has also forced the internal displacement of over 2,000,000 people since its rebellion began in 1986.

Kony received a surge of attention in early March 2012 with the release of ‘Kony 2012,’ a thirty minute documentary, was made by filmaker Jason Russell for the campaign group Invisible Children Inc.

read more »

Amor Fati

‘Amor fati‘ is a Latin phrase loosely translating to ‘love of fate.’ It is used to describe an attitude in which one sees everything that happens in one’s life, including suffering and loss, as good. Moreover, it is characterized by an acceptance of the events or situations that occur in one’s life. The phrase has been linked to the writings of Marcus Aurelius, who did not himself use the words (he wrote in Greek, not Latin), but was popularized in Friedrich Nietzsche’s writings and is representative of the general outlook on life he articulates:

‘I want to learn more and more to see as beautiful what is necessary in things; then I shall be one of those who make things beautiful. Amor fati: let that be my love henceforth! I do not want to wage war against what is ugly. I do not want to accuse; I do not even want to accuse those who accuse. Looking away shall be my only negation. And all in all and on the whole: some day I wish to be only a Yes-sayer.’ ‘My formula for greatness in a human being is amor fati: that one wants nothing to be different, not forward, not backward, not in all eternity. Not merely bear what is necessary, still less conceal it—all idealism is mendaciousness in the face of what is necessary—but love it.’

Eternal Return

Eternal return is a concept which posits that the universe has been recurring, and will continue to recur, in a self-similar form an infinite number of times across infinite time or space. The concept, initially inherent in Indian philosophy, was later found in ancient Egypt and was subsequently taken up by the Pythagoreans and Stoics in Greece. With the decline of antiquity and the spread of Christianity, the concept fell into disuse in the western world, though Friedrich Nietzsche resurrected it as a thought experiment to argue for ‘amor fati’ (seeing everything that happens in one’s life, including suffering and loss, as good).

The basic premise proceeds from the assumption that the probability of a world coming into existence exactly like our own is finite. If either time or space are infinite, then mathematics tells us that our existence will recur an infinite number of times. In 1871, Louis Auguste Blanqui, assuming a Newtonian cosmology where time and space are infinite proceeded to show that the eternal recurrence was a mathematical certainty. In the post-Einstein period, there are doubts that time or space is in fact infinite, but many models exist which provide the notion of spatial or temporal infinity required by the eternal return hypothesis.

read more »