The Committee for Skeptical Inquiry (CSI), formerly known as the Committee for the Scientific Investigation of Claims of the Paranormal (CSICOP), is a program within the U.S. non-profit organization Center for Inquiry (CFI), whose stated purpose is to ‘encourage the critical investigation of paranormal and fringe-science claims from a responsible, scientific point of view and disseminate factual information about the results of such inquiries to the scientific community and the public.’

CSI was founded in 1976 by skeptic and secular humanist Paul Kurtz to counter what he regarded as an uncritical acceptance of, and support for, paranormal claims by both the media and society in general. Its philosophical position is one of scientific skepticism. CSI’s fellows have included many notable scientists, Nobel laureates, philosophers, educators, authors, and celebrities. It is headquartered in Amherst, New York.

read more »

Committee for Skeptical Inquiry

Bill Nye

Bill Nye (b. 1955) is an American science educator, comedian, television host, actor, writer, and scientist who began his career as a mechanical engineer at Boeing. He is best known as the host of the Disney/PBS children’s science show ‘Bill Nye the Science Guy’ and for his many subsequent appearances in popular media as a science educator.

Nye was born in Washington, D.C., to Jacqueline Nye, a codebreaker during World War II, and Edwin Darby Nye, also a World War II veteran, whose experience in a Japanese prisoner of war camp led him to become a sundial enthusiast. Bill is a former fourth-generation Washington resident through his father’s side of the family. He studied mechanical engineering at Cornell University (where one of his professors was Carl Sagan).

read more »

Catching Fire

‘Catching Fire: How Cooking Made Us Human‘ (2009) is a book by British primatologist Richard Wrangham forwarding the hypothesis that cooking food was an essential element in the physiological evolution of human beings.

Humans are the only species that cook their food and Wrangham argues Homo erectus emerged about two million years years ago as a result of this unique trait. Cooking had profound evolutionary effect because it increased food efficiency by permitting human ancestors to spend less time foraging, chewing, and digesting. H. erectus developed via a smaller, more efficient digestive tract which freed up energy to enable larger brain growth.

read more »

How to Solve It

How to Solve It (1945) is a small volume by mathematician George Pólya describing methods of problem solving.

He suggests four steps when solving a mathematical problem: 1) First, understand the problem; 2) After understanding, then make a plan; 3) Carry out the plan; and; 4) Look back on your work — how could it be better? If this technique fails, Pólya advises: ‘If you can’t solve a problem, then there is an easier problem you can solve: find it.’ Or: ‘If you cannot solve the proposed problem, try to solve first some related problem. Could you imagine a more accessible related problem?’

read more »

Thinking, Fast and Slow

Thinking, Fast and Slow is a 2011 book by Nobel Memorial Prize winner in Economics Daniel Kahneman which summarizes research that he conducted over decades, often in collaboration with cognitive scientist Amos Tversky. It covers all three phases of his career: his early days working on cognitive biases (unknowingly using poor judgement), prospect theory (the tendency to base decisions on the potential value of losses and gains rather than the final outcome), and his later work on happiness (e.g. positive psychology).

The book’s central thesis is a dichotomy between two modes of thought: System 1 is fast, instinctive and emotional; System 2 is slower, more deliberative, and more logical. The book delineates cognitive biases associated with each type of thinking, starting with Kahneman’s own research on loss aversion (the tendency to favor avoiding losses over acquiring gains). From framing choices (the tendency to avoid risk when a positive context is presented and seek risks when a negative one is) to attribute substitution (using an educated guess to fill in missing information), the book highlights several decades of academic research to suggest that people place too much confidence in human judgment.

read more »

Attribute Substitution

Attribute substitution is a psychological process thought to underlie a number of cognitive biases and perceptual illusions. It occurs when an individual has to make a judgment (of a target attribute) that is computationally complex, and instead substitutes a more easily calculated heuristic (‘rule of thumb’) attribute. This substitution is thought of as taking place in the automatic intuitive judgment system, rather than the more self-aware reflective system.

Hence, when someone tries to answer a difficult question, they may actually answer a related but different question, without realizing that a substitution has taken place. This explains why individuals can be unaware of their own biases, and why biases persist even when the subject is made aware of them. It also explains why human judgments often fail to show regression toward the mean.

read more »

Heuristic

A heuristic [hyoo-ris-tik] (Greek: ‘find’ or ‘discover’) is a practical way to solve a problem. It is better than chance, but does not always work. A person develops a heuristic by using intelligence, experience, and common sense. Trial and error is the simplest heuristic, but one of the weakest. ‘Rule of thumb’ and ‘educated guesses’ are other names for simple heuristics. Since a heuristic is not certain to get a result, there are always exceptions.

Sometimes heuristics are rather vague: ‘look before you leap’ is a guide to behavior, but ‘think about the consequences’ is a bit clearer. Sometimes a heuristic is a whole set of stages. When doctors examines a patient, they go through a series of tests and observations. They may not find out what is wrong, but they give themselves the best chance of succeeding. This is called a diagnosis. In computer science, a ‘heuristic’ is a kind of algorithm (a step-by-step list of directions that need to be followed to solve a problem).

read more »

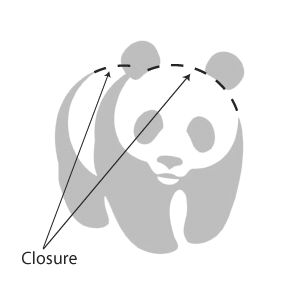

Closure

Closure or need for closure are psychological terms that describe the desire or need individuals have for information that will allow them to conclude an issue that had previously been clouded in ambiguity and uncertainty. Upon reaching this conclusion, they are now able to attain a state of ‘epistemic closure’.

The term ‘cognitive closure’ has been defined as ‘a desire for definite knowledge on some issue and the eschewal of confusion and ambiguity.’ Need for closure is a phrase used by psychologists to describe an individual’s desire for a firm solution as opposed to enduring ambiguity.

read more »

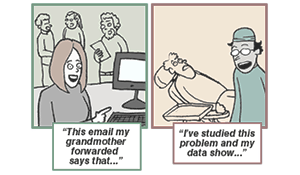

False Balance

Today, false balance is used to describe a perceived or real media bias, where journalists present an issue as being more balanced between opposing viewpoints than the evidence actually supports.

Journalists may present evidence and arguments out of proportion to the actual evidence for each side, or may even actually suppress information which would establish one side’s claims as baseless. False balance is also often found in political reports, company press releases, and general information from organizations with special interest groups in promoting their respective agendas.

read more »

Ice-nine

Ice-nine is a fictional material appearing in Kurt Vonnegut’s novel ‘Cat’s Cradle.’ Ice-nine is supposedly a polymorph of water more stable than common ice; instead of melting at 0 °C (32 °F), it melts at 45.8 °C (114.4 °F). When ice-nine comes into contact with liquid water below 45.8 °C (thus effectively becoming supercooled), it acts as a seed crystal and causes the solidification of the entire body of water, which quickly crystallizes as more ice-nine.

In the story, it is developed by the Manhattan Project for use as a weapon, but abandoned when it becomes clear that any quantity of it would have the power to destroy all life on earth. As people are mostly water, ice-nine kills nearly instantly when ingested or brought into contact with soft tissues exposed to the bloodstream, such as the eyes. A global catastrophe involving freezing the world’s oceans with ice-nine is used as a plot device in Vonnegut’s novel.

read more »

Loss Aversion

In economics and decision theory, loss aversion refers to people’s tendency to strongly prefer avoiding losses to acquiring gains. Most studies suggest that losses are twice as powerful, psychologically, as gains. The concept was first demonstrated by psychologists Amos Tversky and Daniel Kahneman. John List, Chairman of the University of Chicagos’ department of economics has said: ‘It’s a deeply ingrained behavioral trait. .. that all human beings have — this underlying phenomenon that ‘I really, really dislike losses, and I will do all I can to avoid losing something.’

Loss aversion leads to risk aversion when people evaluate an outcome comprising similar gains and losses; since people prefer avoiding losses to making gains. Loss aversion may also explain sunk cost effects, where people justify increased investment in a decision, based on the cumulative prior investment, despite new evidence suggesting that the cost, starting today, of continuing the decision outweighs the expected benefit.

read more »

Endowment Effect

In behavioral economics, the endowment effect (also known as divestiture aversion) is the hypothesis that a person’s willingness to accept (WTA) compensation for a good is greater than their willingness to pay (WTP) for it once their property right to it has been established. People will pay more to retain something they own than to obtain something owned by someone else—even when there is no cause for attachment, or even if the item was only obtained minutes ago. This is due to the fact that once you own the item, foregoing it feels like a loss, and humans are loss-averse.

The endowment effect contradicts the Coase theorem (a theory of economic efficiency), and was described as inconsistent with standard economic theory which asserts that a person’s willingness to pay (WTP) for a good should be equal to their willingness to accept (WTA) compensation to be deprived of the good, a hypothesis which underlies consumer theory and indifference curves.

read more »