A folk devil is a person or group of people who are portrayed in folklore or the media as outsiders and deviant, and are blamed for crimes or other sorts of social problems. The pursuit of folk devils frequently intensifies into a mass movement that is called a moral panic. When a moral panic is in full swing, the folk devils are the subject of loosely organized but pervasive campaigns of hostility through gossip and the spreading of urban legends. The concept of the folk devil was introduced by sociologist Stanley Cohen in 1972, in his study ‘Folk Devils and Moral Panics,’ which analyzed media controversies concerning the Mods and Rockers subcultures in the United Kingdom of the 1960s.

The basic pattern of agitations against folk devils can be seen in the history of witch hunts and similar manias of persecution (Christian Europeans branded adherents of the rival faiths folk devils). Minorities and immigrants have often been seen as folk devils; in the long history of anti-Semitism, which frequently targeted Jews with allegations of dark, murderous practices, such as blood libel; or the Roman persecution of Christians (blaming the military reverses suffered by the Roman Empire on the Christians’ abandonment of paganism). In modern times, political and religious leaders in many nations have sought to present atheists and secularists as deviant outsiders who threaten the social and moral order.

Folk Devil

Colossus of Rhodes

The Colossus of Rhodes was a statue of the Greek god Helios, erected in the city of Rhodes on the Greek island of Rhodes by Greek sculptor Chares of Lindos between 292 and 280 BC. It is considered one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World. It was constructed to celebrate Rhodes’ victory over the ruler of Cyprus, Antigonus I Monophthalmus, who unsuccessfully besieged Rhodes in 305 BC. Before its destruction, it stood over 30 meters (107 ft) high, making it one of the tallest statues of the ancient world.

read more »

Scramble for Africa

The Scramble for Africa, also known as the Race for Africa or African fever, was a process of invasion, attack, occupation, and annexation of African territory by European powers during the New Imperialism period, between 1881 and World War I in 1914. As a result of the heightened tension between European states in the last quarter of the 19th century, the partitioning of Africa may be seen as a way for the Europeans to eliminate the threat of a Europe-wide war over Africa.

Popular European ideas in the 19th century also aided the partitioning of Africa. The eugenics movement and racism helped to foster European expansionist policy. The last 20 years of the nineteenth century saw transition from ‘informal imperialism’ of control through military influence and economic dominance to that of direct rule. Many African polities, states and rulers (such as the Ashanti, the Abyssinians, the Moroccans and the Dervishes) sought to resist this wave of European aggression.

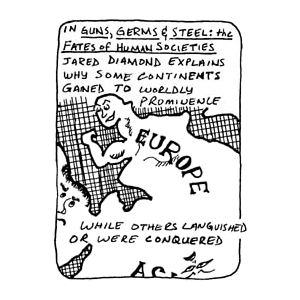

Guns, Germs, and Steel

‘Guns, Germs, and Steel: The Fates of Human Societies’ is a 1997 book by Jared Diamond, professor of geography and physiology at UCLA. The book’s title is a reference to the means by which European nations conquered populations of other areas and maintained their dominance, despite often being vastly outnumbered – superior weapons provided immediate military superiority (guns); Eurasian diseases weakened and reduced local populations, making it easier to maintain control over them (germs) and centralized government promoted nationalism and powerful military organizations (steel).

The book attempts to explain why Eurasian civilizations (including North Africa) have survived and conquered others, while attempting to refute the belief that Eurasian hegemony is due to genetic superiority. Diamond argues that the gaps in power and technology between human societies originate in environmental differences, which are amplified by various positive feedback loops. When cultural or genetic differences have favored Eurasians (for example Chinese centralized government, or improved disease resistance among Eurasians), these advantages were only created due to the influence of geography and were not inherent in the Eurasian genomes.

Operation Mincemeat

Operation Mincemeat was a successful British deception plan during World War II. As part of Operation Barclay, a plan to cover the intended invasion of Italy from North Africa, Mincemeat helped to convince the German high command that the Allies planned to invade Greece and Sardinia in 1943 instead of Sicily, the actual objective.

This was accomplished by persuading the Germans that they had, by accident, intercepted ‘top secret’ documents giving details of Allied war plans. The documents were attached to a corpse deliberately left to wash up on a beach in Punta Umbría in Spain.

read more »

Pickelhaube

The Pickelhaube (from the old German pickel, ‘point’ or ‘pickaxe;’ and haube, ‘bonnet’) was a spiked helmet worn in the 19th and 20th centuries by German military, firefighters, and police. Although typically associated with the Prussian army, the helmet enjoyed wide use among uniformed occupations in the Western world. It was originally designed in 1842 by King Frederick William IV of Prussia, maybe as a copy of similar helmets that were adopted at the same time by the Russian military.It is not clear whether this was a case of imitation, or parallel invention.

Pith Helmet

The pith helmet (also known as the safari helmet, sun helmet, topee, sola topee, salacot or topi) is a lightweight cloth-covered helmet made of cork or pith (typically pith from the sola Indian swamp growth). Designed to shade the wearer’s head and face from the sun, pith helmets were once often worn by Westerners in the tropics.

Crude forms of pith helmets had existed as early as the 1840s, but it was around 1870 that the pith helmet became popular with military personnel in Europe’s tropical colonies. The Franco-Prussian War had popularized the German Pickelhaube, which may have influenced the distinctive design of the pith helmet. Such developments may have merged with a traditional design from the Philippines, the salakot. The alternative name salacot (also written salakhoff) appears frequently in Spanish and French sources; it comes from the Tagalog word salacsac (or Salaksak).

CSA Dollar

The Confederate States of America dollar was first issued into circulation in April 1861, when the Confederacy was only two months old, and on the eve of the outbreak of the Civil War. At first, Confederate currency was accepted throughout the South as a medium of exchange with high purchasing power. As the war progressed, however, confidence in the ultimate success waned, the amount of paper money increased, and their dates of redemption were extended further into the future.

The inevitable result was depreciation of the currency, and soaring prices characteristic of inflation. For example, by the end of the war, a cake of soap could sell for as much as $50 and an ordinary suit of clothes was $2,700. Near the end of the war, the currency became practically worthless as a medium of exchange. When the Confederacy ceased to exist as a political entity at the end of the war, the money lost all value as fiat currency.

Augmented Reality

Augmented reality (AR) refers to a display in which simulated imagery, graphics, or symbology is superimposed on a view of the surrounding environment. It is related to a more general concept called mediated reality in which a view of reality is modified (possibly even diminished rather than augmented) by a computer. The term is believed to have been coined in 1990 by Thomas Caudell, an employee of Boeing at the time.

read more »

Numbers Station

Numbers stations are shortwave radio stations of uncertain origin. They generally broadcast artificially generated voices reading streams of numbers, words, letters (sometimes using a spelling alphabet), tunes or Morse code. They are in a wide variety of languages and the voices are usually female, though sometimes male or children’s voices are used. Numbers stations appear and disappear over time (although some follow regular schedules), and their overall activity has increased slightly since the early 1990s.

Evidence supports popular assumptions that the broadcasts are used to send messages to spies. This usage has not been publicly acknowledged by any government that may operate a numbers station, but in 1892, the United States tried the Cuban Five for spying for Cuba. The group had received and decoded messages that had been broadcast from a Cuban numbers station. In 2009, the United States charged Walter Kendall Myers with conspiracy to spy for Cuba and receiving and decoding messages broadcast from a numbers station operated by the Cuban Intelligence Service.

FNG Syndrome

The term ‘Fucking New Guy‘ (FNG) is a derogatory term for new recruits, made popular by US troops in the Vietnam war. Every unit had an FNG, and the term was used across all unit types, from front line combat through to support and medical units. The term was not gender specific; female personnel could be FNGs as well.

FNGs were an important part of the group dynamic of US units in Vietnam and their treatment had at its core an overall sense of ‘us’ (those with experience of the war) and ‘them’ (those who were back in the United States). As one soldier said, FNGs were ‘still shitting stateside chow.’ It was in combat units that the FNG was truly ignored and hated by his colleagues. An FNG in a combat unit was ‘treated as a non-person, a pariah to be shunned and scorned, almost vilified, until he passed that magic, unseen line to respectability.’

read more »

Spider Hole

A spider hole is U.S. military parlance for a camouflaged one-man foxhole, used for observation. They are typically a shoulder-deep, protective, round hole, often covered by a camouflaged lid, in which a soldier can stand and fire a weapon. A spider hole differs from a foxhole in that a foxhole is usually deeper and designed to emphasize cover rather than concealment.

The term is usually understood to be an allusion to the camouflaged hole constructed by the trapdoor spider. According to United States Marine Corps historian Major Chuck Melson, the term originated in the American Civil War, when it meant a hastily-dug foxhole. Spider holes were used during World War II by Japanese forces in many Pacific battlefields, including Leyte in the Philippines and Iwo Jima. The Japanese called them ‘octopus pots.’ On 13 December 2003, U.S. troops in Iraq undertaking Operation Red Dawn discovered Iraqi dictator Saddam Hussein hiding in what was characterized as a spider hole in a farmhouse near his hometown of Tikrit.