The Hero with a Thousand Faces (first published in 1949) is a non-fiction book, and seminal work of comparative mythology by Joseph Campbell. In this publication, Campbell discusses his theory of the journey of the archetypal hero found in world mythologies. Since publication, Campbell’s theory has been consciously applied by a wide variety of modern writers and artists. The best known is perhaps George Lucas, who has acknowledged a debt to Campbell regarding the stories of the ‘Star Wars’ films.

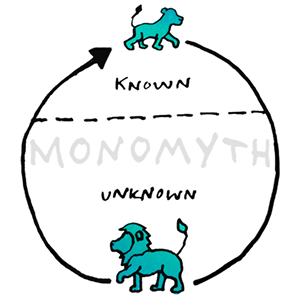

Campbell explores the theory that important myths from around the world which have survived for thousands of years all share a fundamental structure, which Campbell called the monomyth and ‘the hero’s journey. ‘In a well-known quote from the introduction to ‘The Hero with a Thousand Faces,’ Campbell summarized the monomyth: ‘A hero ventures forth from the world of common day into a region of supernatural wonder: fabulous forces are there encountered and a decisive victory is won: the hero comes back from this mysterious adventure with the power to bestow boons on his fellow man.’

In laying out the monomyth, Campbell describes a number of stages or steps along this journey. The hero starts in the ordinary world, and receives a call to enter an unusual world of strange powers and events (‘a call to adventure’). If the hero accepts the call to enter this strange world, the hero must face tasks and trials (‘a road of trials’), and may have to face these trials alone, or may have assistance. At its most intense, the hero must survive a severe challenge, often with help earned along the journey. If the hero survives, the hero may achieve a great gift (the goal or ‘boon’), which often results in the discovery of important self-knowledge. The hero must then decide whether to return with this boon (‘the return to the ordinary world’), often facing challenges on the return journey. If the hero is successful in returning, the boon or gift may be used to improve the world (‘the application of the boon’).

Very few myths contain all of these stages—some myths contain many of the stages, while others contain only a few; some myths may have as a focus only one of the stages, while other myths may deal with the stages in a somewhat different order. These stages may be organized in a number of ways, including division into three sections: ‘Departure’ (sometimes called ‘Separation’), ‘Initiation’ and ‘Return.’ Departure deals with the hero venturing forth on the quest, Initiation with the hero’s various adventures along the way, and Return with the hero’s return home with knowledge and powers acquired on the journey.

The classic examples of the monomyth relied upon by Campbell and other scholars include the stories of Osiris, Prometheus, the Buddha, Moses, and Christ, although Campbell cites many other classic myths from many cultures which rely upon this basic structure.

While Campbell offers a discussion of the hero’s journey by using the Freudian concepts popular in the 1940s and 1950s, the monomythic structure is not tied to these concepts. Similarly, Campbell uses a mixture of Jungian archetypes, unconscious forces, and Arnold van Gennep’s structuring of rites of passage rituals to provide some illumination.

Campbell used the work of early 20th century theorists to develop his model of the hero (particularly structuralism), including Freud (particularly the Oedipus complex), Carl Jung (archetypal figures and the collective unconscious), and Arnold Van Gennep (the three stages of ‘The Rites of Passage,’ translated by Campbell into ‘Departure, Separation, and Return’). Campbell also looked to the work of ethnographers James Frazer and Franz Boas and psychologist Otto Rank. He borrowed the term monomyth from James Joyce’s ‘Finnegans Wake.’ In addition, Joyce’s ‘Ulysses’ was also highly influential in the structuring of ‘The Hero with a Thousand Faces.’

One of the questions that has been raised about the way that Campbell laid out the monomyth was that it focused on the masculine journey. Although this was not altogether true—the princess of the Grimms’ ‘The Frog Prince’ tale and the saga of the hero-goddess Inanna’s descent into the underworld feature prominently in Campbell’s schema—it was, nonetheless, a question that has been raised about the book since its publication.

Late in his life, Campbell had this to say: ‘All of the great mythologies and much of the mythic story-telling of the world are from the male point of view. When I was writing ‘The Hero with a Thousand Faces’ and wanted to bring female heroes in, I had to go to the fairy tales. These were told by women to children, you know, and you get a different perspective. It was the men who got involved in spinning most of the great myths. The women were too busy; they had too damn much to do to sit around thinking about stories.’

‘In ‘The Odyssey,’ you’ll see three journeys. One is that of Telemachus, the son, going in quest of his father. The second is that of the father, Odysseus, becoming reconciled and related to the female principle in the sense of male-female relationship, rather than the male mastery of the female that was at the center of ‘The Iliad.’ And the third is of Penelope herself, whose journey is […] endurance. Out in Nantucket, you see all those cottages with the widow’s walk up on the roof: when my husband comes back from the sea. Two journeys through space and one through time.’

‘Artists are magical helpers. Evoking symbols and motifs that connect us to our deeper selves, they can help us along the heroic journey of our own lives. The artist is meant to put the objects of this world together in such a way that through them you will experience that light, that radiance which is the light of our consciousness and which all things both hide and, when properly looked upon, reveal. The hero journey is one of the universal patterns through which that radiance shows brightly. What I think is that a good life is one hero journey after another. Over and over again, you are called to the realm of adventure, you are called to new horizons. Each time, there is the same problem: do I dare? And then if you do dare, the dangers are there, and the help also, and the fulfillment or the fiasco. There’s always the possibility of a fiasco. But there’s also the possibility of bliss.

The Hero with a Thousand Faces has influenced a number of artists, musicians, poets, and filmmakers, including Bob Dylan, Jim Morrison and George Lucas. Mickey Hart, Bob Weir and Jerry Garcia of the Grateful Dead had long noted Campbell’s influence and agreed to participate in a seminar with him in 1986 entitled ‘From Ritual to Rapture.’

George Lucas’ deliberate use of Campbell’s theory of the monomyth in the making of the Star Wars movies is well documented. Christopher Vogler, a Hollywood film producer and writer, wrote a memo for Disney Studios on the use of ‘The Hero with a Thousand Faces’ as a guide for scriptwriters; this memo influenced the creation of such films as ‘Aladdin,’ ‘The Lion King,’ and ‘Beauty and the Beast.’ Vogler later expanded the memo and published it as the book ‘The Writer’s Journey,’ which became the inspiration for a number of successful Hollywood films and is believed to have been used in the development of the Matrix series.

Novelist Richard Adams acknowledges a debt to Campbell’s work, and specifically to the concept of the monomyth. In his best known work, ‘Watership Down,’ Adams uses extracts from ‘The Hero with a Thousand Faces’ as chapter epigrams.

Author Neil Gaiman, whose work is frequently seen as exemplifying the monomyth structure, says that he started the book but refused to finish it: ‘I think I got about half way through ‘The Hero with a Thousand Faces’ and found myself thinking if this is true—I don’t want to know. I really would rather not know this stuff. I’d rather do it because it’s true and because I accidentally wind up creating something that falls into this pattern than be told what the pattern is.’

The Daily Omnivore

Everything is Interesting

Leave a comment