An amplified cactus is a cactus plant used as a musical instrument. It harnesses the acoustic properties of a cactus (preferably a Denmoza or Geohintonia), by applying contact microphones and amplifying their projection and tone. The effect is somewhat ethereal: Vivien Schweitzer of The New York Times reports ‘Jason Treuting played an amplified cactus, running his hand over the plant’s unfriendly spikes to produce an alluring sound like a babbling brook.’

The amplified cactus is a medium rarely written for, even in the contemporary music genre. John Cage, perhaps one of the most recognizable names in the contemporary music genre, composed Child of Tree (1975) and Branches (1976) for what he described as ‘amplified plant materials.’ Cage was a large proponent of chance music and felt that the organic nature of music without man-made instruments was very strong and influential. Another of the most famous pieces for amplified cactus is called Degrees of Separation ‘Grandchild of Tree’ by Paul Rudy which received mention at the Bourges International Competition for Electroacoustic Music in 2000.

Amplified Cactus

Klein Bottle

In mathematics, the Klein bottle is a geometrical object, named after the German mathematician Felix Klein. He described it in 1882, and named it Klein’sche Fläche (Klein surface). Like the Möbius strip, it only has one surface. Mathematicians call this a non-orientable surface. Klein bottles only exist in four-dimensional space, but a model of a Klein bottle can be made in 3D.

This model is different from the original because at some point the shape touches itself. In 3D, part of the shape is ‘inside’ the rest. Because the surface is non-orientable, there is no ‘inside’ or ‘outside.’ This means that if a liquid were filled ‘in the bottle,’ it would run down its surface. This may not be true for the 3D models of the bottle.

Mathematical Beauty

Many mathematicians derive aesthetic pleasure from their work, and from mathematics in general. They express this pleasure by describing mathematics as beautiful. Sometimes mathematicians describe mathematics as an art form or, at a minimum, as a creative activity. Hungarian mathematician Paul Erdős expressed his views on the ineffability of mathematics when he said, ‘Why are numbers beautiful? It’s like asking why is Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony beautiful. If you don’t see why, someone can’t tell you. I know numbers are beautiful. If they aren’t beautiful, nothing is.’

Comparisons are often made with music and poetry. British mathematician Bertrand Russell expressed his sense of mathematical beauty in these words: ‘Mathematics, rightly viewed, possesses not only truth, but supreme beauty — a beauty cold and austere, like that of sculpture, without appeal to any part of our weaker nature, without the gorgeous trappings of painting or music, yet sublimely pure, and capable of a stern perfection such as only the greatest art can show. The true spirit of delight, the exaltation, the sense of being more than Man, which is the touchstone of the highest excellence, is to be found in mathematics as surely as poetry.’

Möbius Strip

The Möbius strip [mo-bee-uhs] is a surface with only one side and only one edge. It can be made using a strip of paper by gluing the two ends together with a half-twist. The twisting is possible in two directions; so there are two different (mirror-image) Möbius strips.

The Möbius strip was discovered independently by the German mathematicians August Ferdinand Möbius and Johann Benedict Listing in 1858. The Mobius strip is known for its unusual properties. A bug crawling along the center line of the loop would go around twice before coming back to its starting point. Cutting along the center line of the loop creates one longer band, not two.

Flammarion Woodcut

The Flammarion [fla-ma-ryawn] woodcut is an anonymous wood engraving (once believed to be a woodcut), so named because its first documented appearance is in Camille Flammarion’s 1888 book L’atmosphère: météorologie populaire (‘The Atmosphere: Popular Meteorology’).

The engraving depicts a man, dressed as a mediaeval pilgrim and carrying a pilgrim’s staff, who peers through the sky as if it were a curtain to look at the hidden workings of the universe. One of the elements of the cosmic machinery bears a strong resemblance to traditional pictorial representations of the ‘wheel in the middle of a wheel’ (Merkabah).

Wood Engraving

Wood engraving is a technique in printmaking where the ‘matrix’ worked by the artist is a block of wood. It is a variety of woodcut and so a relief printing technique, where ink is applied to the face of the block and printed by using relatively low pressure. A normal engraving, like an etching, has a metal plate as a matrix and is printed by the intaglio method.

Wood engraving traditionally utilizes the end grain of wood as a medium for engraving, while in the older technique of woodcut the softer side grain is used. The technique of wood engraving developed at the end of the 18th century and the beginning of the 19th century, with the works of Thomas Bewick.

Woodcut

Woodcut—formally known as xylography—is a relief printing artistic technique in printmaking in which an image is carved into the surface of a block of wood. the non-printing parts are removed, typically with gouges. The areas to show ‘white’ are cut away with a knife or chisel, leaving the characters or image to show in ‘black’ at the original surface level.

The block is cut along the grain of the wood (unlike wood engraving where the block is cut in the end-grain). Beechwood is commonly used in Europe. Cherry wood is favored in Japan. The surface is covered with ink by rolling over the surface with an ink-covered roller (brayer), leaving ink upon the flat surface but not in the non-printing areas. Multiple colors can be printed by keying the paper to a frame around the woodblocks (where a different block is used for each color).

Stendhal Syndrome

Stendhal [sten-dahl] syndrome (also known as hyperkulturemia and Florence syndrome) is a psychosomatic illness that causes rapid heartbeat, dizziness, fainting, confusion and even hallucinations when an individual is exposed to art, usually when the art is particularly beautiful or a large amount of art is in a single place. The term can also be used to describe a similar reaction to a surfeit of choice in other circumstances, e.g. when confronted with immense beauty in the natural world.

The condition is named after the famous 19th century French author Stendhal (Henri-Marie Beyle), who described his experience with the phenomenon during his 1817 visit to Florence, Italy. Although there are many descriptions of people becoming dizzy and fainting while taking in Florentine art, especially at the Uffizi, dating from the early 19th century on, the syndrome was only named in 1979, when it was described by Italian psychiatrist Graziella Magherini, who observed and described more than 100 similar cases among tourists and visitors in Florence.

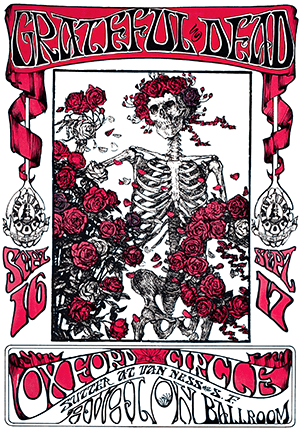

Stanley Mouse

Stanley Mouse (b. 1940) is an American artist, best known for his 1960s psychedelic rock concert poster designs and Grateful Dead album cover art. He got his start in the Kustom Kulture scene working for Ed ‘Big Daddy’ Roth in 1958. The posters he produced were heavily influenced by Art Nouveau graphics, particularly the works of Alphonse Mucha and Edmund Joseph Sullivan.

Material associated with psychedelics, such as Zig-Zag rolling papers, were also referenced. Producing posters advertising for such musical groups as Big Brother and the Holding Company, Quicksilver Messenger Service, and Grateful Dead led to meeting the musicians and making contacts that were later to prove fruitful. Mouse and artist Alton Kelley are credited with creating the skeleton and roses image that became the Grateful Dead’s archetypal iconography, and Journey’s wings and beetles that appeared on their album covers from 1977 to 1980.

Chartjunk

Chartjunk refers to all visual elements in charts and graphs that are not necessary to comprehend the information represented on the graph, or that distract the viewer from this information. Examples of unnecessary elements which might be called chartjunk include heavy or dark grid lines, unnecessary text or inappropriately complex typefaces, ornamented chart axes and display frames, pictures or icons within data graphs, ornamental shading and unnecessary dimensions.

Another kind of chartjunk skews the depiction and makes it difficult to understand the real data being displayed. Examples of this type include items depicted out of scale to one another, noisy backgrounds making comparison between elements difficult in a chart or graph, and 3-D simulations in line and bar charts. The term was coined by American statistician Edward Tufte in his 1983.

Bowers and Wilkins Nautilus

The Nautilus is a Bowers & Wilkins concept loudspeaker first released in 1993. It uses tapering tubes filled with absorbent wadding to reduce resonances to an insignificant minimum. Nautilus Tapering Tubes are fitted to nearly all Bowers & Wilkins speakers, even when they’re not visible to the eye. Tapering the tube enables you to make it shorter for the same level of absorption; it acts like a horn in reverse – reducing the sound level instead of increasing it.

The limit of this type of loading is reached when the wavelength gets small enough to be comparable with the diameter of the tube. To maintain the effectiveness of tube loading, you must restrict the bandwidth of each driver. This is one reason why the Nautilus loudspeaker is divided into a 4-way system. A more complex type of loading is required to cover a wider bandwidth and the sphere/tube enclosure was developed for the Nautilus 800 Series.

Ferruccio Busoni

Ferruccio [fer-root-chaw] Busoni [byoo-soh-nee] (1866 – 1924) was an Italian composer. His philosophy that ‘Music was born free; and to win freedom is its destiny,’ greatly influenced his students Percy Grainger and Edgard Varèse, both of whom played significant roles in the 20th century opening of music to all sound. In 1907 he published Sketch of a New Esthetic of Music, which discussed the use of electrical and other new sound sources in future music.

He deplored that his own keyboard instrument had conditioned our ears to accept only an infinitesimal part of the infinite gradations of sounds in nature. He wrote of the future of microtonal scales in music, made possible by Cahill’s Dynamophone: ‘Only a long and careful series of experiments, and a continued training of the ear, can render this unfamiliar material approachable and plastic for the coming generation, and for Art.’