A welfare queen is a pejorative phrase used in the United States to describe people who are accused of collecting excessive welfare payments through fraud or manipulation. Reporting on welfare fraud began during the early 1960s, appearing in general interest magazines such as ‘Readers Digest.’

The term entered the American lexicon during Ronald Reagan’s 1976 presidential campaign when he described a ‘welfare queen’ from Chicago’s South Side. Since then, it has become a stigmatizing label placed on recidivist poor mothers, with studies showing that it often carries gendered and racial connotations. Although American women can no longer stay on welfare indefinitely due to the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Act, the term continues to shape American dialogue on poverty.

read more »

Welfare Queen

Wife Acceptance Factor

Wife Acceptance Factor (WAF) refers to design elements that increase the likelihood a wife will approve the purchase of expensive consumer electronics products such as home theater systems and personal computers. Stylish, compact, unobtrusive forms and appealing colors are commonly considered WAF. The term is a tongue-in-cheek play on electronics jargon such as ‘form factor’ and ‘power factor’ and derives from the gender stereotype that men are predisposed to appreciate gadgetry and performance criteria whereas women must be wooed by visual and aesthetic factors.

Larry Greenhill first used the term in 1983, writing for ‘Stereophile’ magazine, but Greenhill credited fellow reviewer and music professor Lewis Lipnick with the coining of the term. Lipnick himself traces the origin to the 1950s when hi-fi loudspeakers were so large that they overwhelmed most living rooms. Lipnick’s wife, actress Lynn-Jane Foreman, arrived at a different term: Marriage Interference Factor (MIF). Foreman suggested that audiophile husbands should balance their large and ugly electronic acquisitions with gifts to the wife made on the basis of similar expense, with opera tickets, jewelry and vacations abroad among the suggestions.

Schreiber Theory

The Schreiber theory is a writer-centered approach to film criticism which holds that the principal author of a film is generally the screenwriter rather than the director. The term was coined by David Kipen, Director of Literature at the US National Endowment for the Arts. In his 2006 book ‘The Schreiber Theory: A Radical Rewrite of American Film History,’ Kipen argues that the influential 1950s-era Auteur theory has wrongly skewed analysis towards a director-centered view of film. In contrast, Kipen believes that the screenwriter has a greater influence on the quality of a finished work and that knowing who wrote a film is ‘the surest predictor’ of how good it will be.

Kipen acknowledges that his writer-centered approach is not new, and pays tribute to earlier critics of Auteur theory such as Pauline Kael and Richard Corliss. He believes that the Auteurist approach remains dominant, however, and that films have suffered as a result of the screenwriter’s role being undervalued. Kipen refers to his book as a ‘manifesto’ and in an interview with the magazine ‘SF360’ stated that he wished to use Schreiber theory as ‘a lever to change the way people think about screenwriting, and movies in general.’ In seeking a name for his theory, Kipen chose the Yiddish word for writer – ‘schreiber’ – in honor of the many early American screenwriters who had Yiddish as their mother tongue.

Auteur Theory

In film criticism, auteur theory holds that a director’s film reflects the director’s personal creative vision, as if they were the primary ‘auteur’ (the French word for ‘author’). In spite of—and sometimes even because of—the production of the film as part of an industrial process, the auteur’s creative voice is distinct enough to shine through all kinds of studio interference and through the collective process.

In law, the film is treated as a work of art, and the auteur, as the creator of the film, is the original copyright holder. Under European Union law, the film director is considered the author or one of the authors of a film, largely as a result of the influence of auteur theory.

read more »

Radium Girls

The Radium Girls were female factory workers who contracted radiation poisoning from painting watch dials with glow-in-the-dark paint at the United States Radium factory in Orange, New Jersey around 1917.

The women, who had been told the paint was harmless, ingested deadly amounts of radium by licking their paintbrushes to sharpen them. Some also painted their fingernails and teeth with the glowing substance. Five of the women challenged their employer in a court case that established the right of individual workers who contract occupational diseases to sue their employers.

read more »

Undark

Undark was a trade name for luminous paint made with a mixture of radioactive radium and zinc sulfide, as produced by the U.S. Radium Corporation between 1917 and 1938. It was used primarily in watch dials.

The people working in the industry who applied the radioactive paint became known as the Radium Girls, because many of them became ill and some died from exposure to the radiation emitted by the radium contained within the product. The product was the direct cause of Radium jaw in the dial painters. Undark was also available as a kit for general consumer use and marketed as glow-in-the-dark paint.

Market Failure

Market failure occurs in economics when the allocation of goods and services by a free market is not efficient. In such cases the pursuit of pure self-interest leads to results that can be improved upon from the societal point-of-view. The first known use of the term by economists was in 1958, but the concept has been traced back to the Victorian philosopher Henry Sidgwick.

A market failure can occur for three main reasons: if the market is monopolized (a small group of businesses hold significant market power), if production of the good or service results in an externality (a cost or benefit that affects an unaffiliated third party), or if the good or service is a ‘public good’ (a non-excludable good like air).

read more »

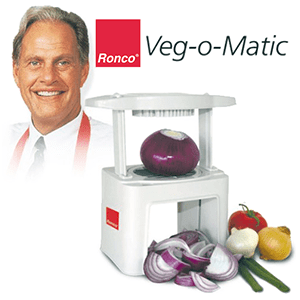

Ron Popeil

Ron Popeil (b. 1935) is an American inventor and marketing personality, best known for his direct response marketing company Ronco. He is well known for his appearances in infomercials for the Showtime Rotisserie (‘Set it, and forget it!’) and for using the phrase, ‘But wait, there’s more!’ on television as early as the mid-1950s. Popeil learned his trade from his father, Samuel, who was also an inventor and carny salesman of kitchen-related gadgets such as the Chop-O-Matic and the Veg-O-Matic. The Chop-O-Matic retailed for US$3.98 and sold over two million units.

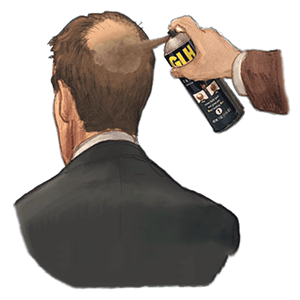

The success of the product caused a problem that marked the entrance of Ron Popeil into television. Chop-O-Matic was efficient at chopping vegetables, but it was impractical for salesmen to carry vegetables for demonstrations. The solution was to tape the demonstration; it was a short step to broadcasting the demonstration as a commercial. Some of his better-known products include: Mr. Microphone (a short-range hand-held radio transmitter that broadcast over FM radios), Showtime Rotisserie (a small rotisserie oven designed for cooking smaller sized portions of meat such as whole chicken and lamb),GLH-9 Hair in a Can Spray, and an Electric Food Dehydrator.

Ronco

Ronco is an American company that manufactures and sells a variety of items and devices, most commonly those used in the kitchen. Ron Popeil founded the company in 1964, and commercials for the company’s products soon became pervasive and memorable, in part thanks to Popeil’s personal sales pitches. The names ‘Ronco’ and ‘Popeil’ and the suffix ‘-O-Matic’ (used in many early product names) became icons of American popular culture and were often referred to by comedians introducing fictional gadgets.

In the beginning, the company chiefly sold inventions developed by Popeil’s father, Samuel ‘S.J.’ Popeil. Products include the Veg-O-Matic and the Popeil Pocket Fisherman. During the 1970s, Ron Popeil began developing products on his own to sell through Ronco. Ronco became a household name with its commercials for kitchen products including the Ginsu knife and Armorcote non-stick pans. Aired frequently, especially during off-hour TV viewing times, these commercials became known for their catchphrases such as ‘…but wait, there’s more!’, ’50-year guarantee’ (later expanded to a ‘lifetime guarantee’), and ‘…now how much would you pay?’

Monkey Tennis

‘Monkey Tennis‘ is a British pop culture phrase, first used in the late 1990s and popular throughout the 2000s. Originating as a joke in a television sitcom, it has come to be commonly used as an example of the hypothetical lowest common denominator television program that it is possible to make.

The term originates from the opening episode of the sitcom ‘I’m Alan Partridge,’ originally broadcast on BBC Two in 1997. In one scene the eponymous character of Partridge, a failed chat show host, desperately attempts to pitch program ideas to uninterested BBC executive who cancelled his first series. After failing to interest him in ideas plucked from thin air such as ‘Arm Wrestling With Chas & Dave,’ ‘Youth Hostelling with Chris Eubank,’ ‘Inner-City Sumo’ and ‘Cooking in Prison,’ Partridge comes up with a final spur-of-the-moment suggestion, ‘Monkey Tennis?,’ which is met with similar disdain.

Horse Opera

A horse opera, or hoss opera, is a western movie or television series that is extremely clichéd or formulaic (in the manner of a soap opera). The term, which was originally coined by silent film-era Western star William S. Hart, is used variously to convey either disparagement or affection.

The name “horse opera” was also derived in part from the musical sequences frequently featured in these films and TV series which depicted a cowboy singing to his horse on-screen. The term “horse opera” is quite loosely defined; it does not specify a distinct sub-genre of the western (as “space opera” does with regard to the science fiction genre).

Taubman Sucks

Taubman Sucks is an award-winning short documentary about a precedent-setting intellectual property lawsuit. The documentary was written and directed by filmmaker Theo Lipfert. The six-minute film explores Taubman v. WebFeats, a lawsuit that involved the complex relationships between domain names, trademarks, and free speech.

As the first ‘sucks.com’ case to reach the level of the United States Court of Appeals, the decision in Taubman v. WebFeats established precedents concerning the non-commercial use of trademarks in domain names.