The Up Series is a series of documentary films produced by Granada Television that have followed the lives of fourteen British children since 1964, when they were seven years old. The documentary has had eight episodes spanning 49 years (one episode every seven years) and the documentary has been broadcast on both ITV and BBC.

The children were selected to represent the range of socio-economic backgrounds in Britain at that time, with the explicit assumption that each child’s social class predetermines their future. Every seven years, the director, Michael Apted, films material from those of the fourteen who choose to participate.

read more »

Up Series

Memetic Engineering

Memetic [meh-met-ik] engineering is a term developed and coined by Leveious Rolando, John Sokol, and Gibran Burchett while they researched and observed the behavior of people after being purposely exposed (knowingly and unknowingly) to certain memetic themes. The term is based on Richard Dawkins’ theory of memes (a proposed basic unit of cultural information).

Memetic engineering refers to the process of developing memes, through ‘meme-splicing’ and ‘memetic synthesis,’ with the intent of altering the behavior of others in society or humanity; the process of creating and developing theories or ideologies based on an analytical study of societies, cultures, their ways of thinking and the evolution of their minds; and the process of modifying human beliefs, thought patterns, etc.

read more »

Woozle Effect

Woozle effect, also known as evidence by citation, or a woozle, occurs when frequent citation of previous publications that lack evidence mislead individuals, groups and the public into thinking or believing there is evidence, and nonfacts become urban myths and factoids (statements presented as a fact, but with no veracity).

Woozle effect is a term coined by criminologist Beverly Houghton in 1979. It describes a pattern of bias seen within social sciences and which is identified as leading to multiple errors in individual and public perception, academia, policy making and government. A woozle is also a claim made about research which is not supported by original findings.

read more »

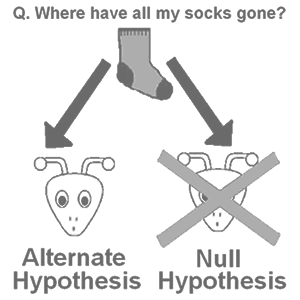

Null Hypothesis

In statistics, a null hypothesis is the ‘no-change’ or ‘no-difference’ hypothesis. The term was first used by English geneticist Ronald Fisher in his book ‘The design of experiments.’ A hypothesis is a proposed explanation for some event or problem. Every experiment has a null hypothesis. If you do an experiment to see if a medicine works, the null hypothesis is that it doesn’t work.

If you do an experiment to see if people like chocolate or vanilla ice-cream better, the null hypothesis is that people like them equally. If you do an experiment to see if either boys or girls can play piano better, the null hypothesis is that boys and girls are equally good at playing the piano. The opposite of the null hypothesis is the alternative hypothesis (a difference does exist: this medicine makes people healthier, people like chocolate ice-cream better than vanilla, or boys are better at playing the piano than girls).

read more »

Type I and Type II Errors

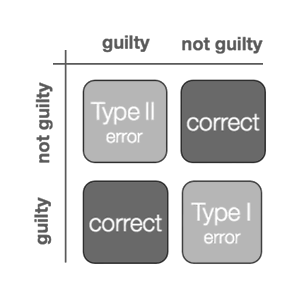

In statistics, Type I and type II errors are errors that happen when a coincidence occurs while doing statistical inference, which gives you a wrong conclusion. A Type I error is saying the original question is false, when it is actually true (e.g. a jury finding an innocent person guilty, a ‘false positive’); a Type II error is saying the original question is true, when it is actually false (e.g. a jury finding a guilty person not guilty, a ‘false negative’ or simply a ‘miss’).

Usually a type I error leads one to conclude that a thing or relationship exists when really it doesn’t: for example, that a patient has a disease being tested for when really the patient does not have the disease, or that a medical treatment cures a disease when really it doesn’t. Examples of type II errors would be a blood test failing to detect the disease it was designed to detect, in a patient who really has the disease; or a clinical trial of a medical treatment failing to show that the treatment works when really it does.

read more »

Tacit Knowledge

Tacit knowledge (as opposed to formal or explicit knowledge) is the kind of knowledge that is difficult to transfer to another person by means of writing it down or verbalizing it. For example, stating to someone that London is in the United Kingdom is a piece of explicit knowledge that can be written down, transmitted, and understood by a recipient.

However, the ability to speak a language, use algebra, or design and use complex equipment requires all sorts of knowledge that is not always known explicitly, even by expert practitioners, and which is difficult to explicitly transfer to users. While tacit knowledge appears to be simple, it has far reaching consequences and is not widely understood.

read more »

Diffusion of Innovations

Diffusion of Innovations is a theory that seeks to explain how, why, and at what rate new ideas and technology spread through cultures. Everett Rogers, a professor of rural sociology, popularized the theory in his 1962 book ‘Diffusion of Innovations.’ He said diffusion is the process by which an innovation is communicated through certain channels over time among the members of a social system.

The origins of the diffusion of innovations theory are varied and span multiple disciplines. Rogers espoused four main elements that influence the spread of a new idea: the innovation, communication channels, time, and a social system.

read more »

Heterophily

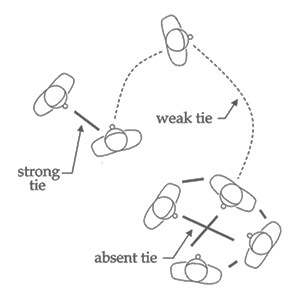

Heterophily [het-er-uh-fil-ee], or ‘love of the different,’ is the tendency of individuals to collect in diverse groups; it is the opposite of homophily (‘love of the same,’ the tendency of individuals to associate and bond with similar others). This phenomenon is notable in successful organizations, where the resulting diversity of ideas is thought to promote an innovative environment. Recently it has become an area of social network analysis. Most of the early work in heterophily was done in the 1960s by sociologist Everett Rogers in his book ‘Diffusion Of Innovations.’

Rogers showed that heterophilious networks were better able to spread innovations. Later, scholars such as Paul Burton, draw connections between modern Social Network Analysis as practiced by Stanford sociologist Mark Granovetter in his theory of weak ties (if A is linked to both B and C, then there is a greater-than-chance probability that B and C are linked to each other) and the work of German sociologist Georg Simmel. Burton found that Simmel’s notion of ‘the stranger’ is equivalent to Granovetter’s weak tie in that both can bridge homophilious networks, turning them into one larger heterophilious network.

Friendship Paradox

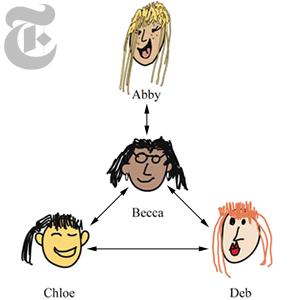

The friendship paradox is the phenomenon first observed by the sociologist Scott L. Feld in 1991 that most people have fewer friends than their friends have, on average. It can be explained as a form of sampling bias (e.g. non-random sample) in which people with greater numbers of friends have an increased likelihood of being observed among one’s own friends. In contradiction to this, most people believe that they have more friends than their friends have.

The same observation can be applied more generally to social networks defined by other relations than friendship: for instance, most people’s sexual partners have (on the average) a greater number of sexual partners than they have. In spite of its apparently paradoxical nature, the phenomenon is real, and can be explained as a consequence of the general mathematical properties of social networks.

read more »

Colors of Noise

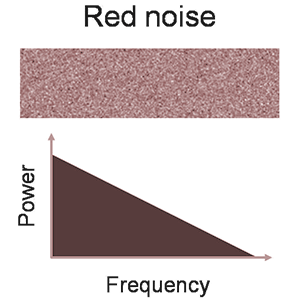

Noises are classified based on their spectral properties; they are named for the color they most resemble in the visible light spectrum. If the sound wave pattern of ‘red noise’ were translated into light waves, the resulting light would be red, and so on. White noise is an audio signal that contains all the frequencies audible to the human ear. It is analogous to white light, which contains all the colors of light visible to the human eye.

Pink noise is a signal that is louder at low frequencies and decreases at a constant rate. It is sometimes referred to as flicker noise particularly when it describes background noise emitted by an electronic device. Pink noise is used to make music, sound effects, or merely as a pleasant background sound and is reported to sound more like the ocean than white noise (which is often compared to the sound of rainfall or TV static) because of its bias towards lower frequencies.

read more »

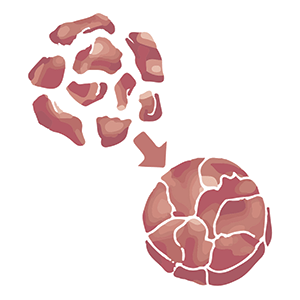

Meat Glue

A transglutaminase is an enzyme first described in 1959 which creates extensively cross-linked, generally insoluble protein polymers (indispensable for organisms to create barriers and stable structures). Examples are blood clots as well as skin and hair. In commercial food processing, transglutaminase is used to bond proteins together. Examples of foods made using the enzyme include imitation crabmeat, and fish balls. It is produced by bacterial fermentation in commercial quantities or extracted from animal blood, and is used in a variety of processes, including the production of processed meat and fish products.

Transglutaminase can be used as a binding agent to improve the texture of protein-rich foods such as surimi (fish paste) or ham. Transglutaminase is also used in molecular gastronomy to meld new textures with existing tastes. Besides these mainstream uses, transglutaminase has been used to create some unusual foods. British chef Heston Blumenthal is credited with the introduction of transglutaminase into modern cooking. Wylie Dufresne, chef of New York’s avant-garde restaurant wd~50, was introduced to transglutaminase by Blumenthal, and invented a ‘pasta’ made from over 95% shrimp thanks to transglutaminase.

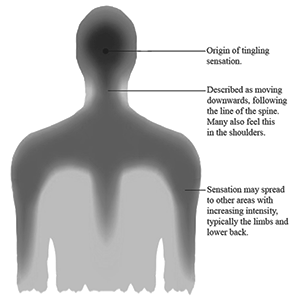

ASMR

The term ‘autonomous sensory meridian response’ (ASMR) is a neologism for a claimed biological phenomenon, characterized as a distinct, pleasurable tingling sensation often felt in the head, scalp or peripheral regions of the body in response to various visual and auditory stimuli.

The phenomenon was first noted through internet culture such as blogs and online videos. Tom Stafford, a professor at the University of Sheffield, says ‘It might well be a real thing, but it’s inherently difficult to research.’

read more »