A calculator watch is a watch with a calculator built into it. Calculator watches first appeared in the Mid 1970s introduced by Pulsar and Hewlett Packard. Several watch manufacturers have made calculator watches over the years, but the Japanese electronics company Casio produced the largest variety of models. In the mid-1980s, Casio created the Data Bank calculator watch, which not only performed calculator functions, but also stored appointments, names, addresses, and phone numbers. The modern eData version of its Data Bank watch has greater memory and the ability to store computer passwords.

When mass produced calculator watches appeared in the early 1980s (with the most being produced in the middle of the decade), the high-tech community’s demand created a ‘feature war’ of one-up-manship between watch manufacturers. However, as the novelty of this new electronic fad watch wore off, they became, much like pocket protectors and thick glasses, associated with nerds and today are no longer considered to be in vogue. Recently, they have come back in style and are worn ‘ironically’ by hipsters.

Calculator Watch

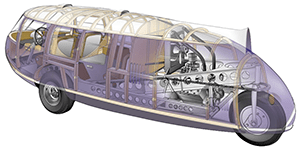

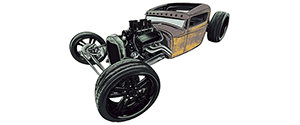

Dymaxion Car

The Dymaxion [dahy-mak-see-uhn] car was a concept car designed by U.S. inventor and architect Buckminster Fuller in 1933. The word Dymaxion is a brand name that Fuller gave to several of his inventions, to emphasize that he considered them part of a more general project to improve humanity’s living conditions. The car had a fuel efficiency of 30 mpg, and could transport 11 passengers.

While Fuller claimed it could reach speeds of 120 miles per hour, the fastest documented speed was 90 miles per hour. Japanese American artist Isamu Noguchi was involved with the development of the Dymaxion car, creating plaster wind tunnel models that were a factor in determining its shape, and during 1934 drove it for an extended road trip through Connecticut with congresswoman Clare Boothe Luce and actress Dorothy Hale.

read more »

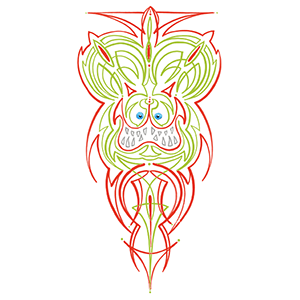

Pin Striping

Pin striping is the application of a very thin line of paint or other material called a pin stripe, and is generally used for decoration. Freehand pin stripers use a specialty brush known as a pinstriping brush. Fine lines in textiles are also called pin stripes. Automotive, bike shops, and do-it-yourself car and motorcycle mechanics use paint pin striping to create their own custom look on the automotive bodies and parts. Pin striping can commonly be seen exhibited on custom motorcycles, such as those built by Choppers Inc., Indian Larry, and West Coast Choppers.

The decorative use of pin striping on motorcycles as it is commonly seen today was pioneered by artists Kenny Howard (aka Von Dutch), and Dean Jeffries, Dennis ‘Gibb’ Gibbish, and Ed ‘Big Daddy’ Roth, are considered pioneers of the Kustom Kulture lifestyle that spawned in the early 1950s, and are widely recognized as the ‘originators of modern pin striping.’

read more »

Jalopy

A jalopy [juh-lop-ee] (also clunker or hooptie or beater) is a decrepit car, often old and in a barely functional state. A jalopy is not a well kept antique car, but a car which is mostly rundown or beaten up.

As a slang term in American English, ‘jalopy’ was noted in 1924 but is now slightly passé. The term was used extensively in the book ‘On the Road’ by Jack Kerouac, first published in 1957, although written from 1947. The equivalent English term is old banger, often shortened to banger, a reference to older poorly maintained vehicles’ tendency to backfire.

read more »

Kustom

Kustoms are modified cars from the 1930s to the early 1960s, done in the customizing styles of that time period. The usage of a ‘K’ rather than a ‘C,’ is believed to have originated with car designer George Barris.

This style generally consists of, but it not limited to starting with a 2-door coupe; lowering the suspension; chopping down the roof line (usually chopped more in the rear to give a ‘raked back’ look, with B-pillars also commonly leaned to enhance this look); sectioning and/or channeling the body (removing a section from the center); certain pieces of side trim are usually removed or ‘shaved’ to make the car look longer, lower and smoother; often bits and pieces of trim from other model cars, are cut, spliced and added to give the car a totally new and interesting ‘line’ to lead the eye in the direction that the Kustomizer wishes it to go; door handles are also ‘shaved’ as well (electric solenoids or cables are installed); buttons are installed in hidden locations and used to open the doors; trunk lids and other pieces of the body can also be altered in this matter.

read more »

Rat Bike

Rat bikes are motorcycles that have fallen apart over time but been kept on the road and maintained for little or no cost by employing kludge (ad hoc) fixes. The concept of keeping a motorcycle in at least minimally operational condition without consideration for appearance has probably characterized motorcycle ownership since its earliest days. The essence of a rat bike is keeping a motorbike on the road for the maximum amount of time while spending as little as possible on it. This calls for adaptation of parts that were not designed to fit the model of bike in question. Most Rat bikes are painted matte black but this is not a requirement.

‘Survival bikes’ are bikes that may appear to be rat bikes, but are not. They are influenced by the ‘Mad Max’ films. The term survival bike itself originated in the British motorcycle press particularly ‘Back Street Heroes,’ and the now-defunct AWoL in the late 1980s and early 1990s.

Rat Rod

A rat rod is a style of hot rod or custom car that, in most cases, imitates (or exaggerates) the early hot rods of the 40s, 50s, and 60s. It is not to be confused with the somewhat closely related ‘traditional’ hot rod, which is an accurate re-creation or period-correct restoration of a hot rod from the same era.

Most rat rods appear ‘unfinished’ (whether they actually are or not), with just the bare essentials to be driven. The rat rod is the visualization of the idea of function over form. Rat rods are meant to be driven, not shown off. Sometimes the customization will include using spare parts, or parts from another car altogether.

read more »

Day For Night

Day for night, also known as nuit américaine (‘American night’), is the name for cinematographic techniques used to simulate a night scene; such as using tungsten-balanced rather than daylight-balanced film stock or with special blue filters and also under-exposing the shot (usually in post-production) to create the illusion of darkness or moonlight. Historically, infrared movie film was used to achieve an equivalent look with black-and-white film.

Another way to achieve this effect is to tune the white balance of the camera to a yellow source if there is no tungsten setting. Another way to make a more believable night scene is to underexpose the footage to the desired degree of night/darkness. This depends on the amount of light shown or believed to be in the given scene. The title of François Truffaut’s film ‘Day for Night’ (1973) is a reference to this technique.

Ryoji Ikeda

Ryoji Ikeda (b. 1966) is a Japanese sound artist who lives and works in Paris. Ikeda’s music is concerned primarily with sound in a variety of ‘raw’ states, such as sine tones and noise, often using frequencies at the edges of the range of human hearing. The conclusion of his album ‘+/-‘ features just such a tone; of it, Ikeda says ‘a high frequency sound is used that the listener becomes aware of only upon its disappearance.’

Rhythmically, Ikeda’s music is highly imaginative, exploiting beat patterns and, at times, using a variety of discrete tones and noise to create the semblance of a drum machine. His work also encroaches on the world of ambient music; many tracks on his albums are concerned with slowly evolving soundscapes, with little or no sense of pulse.

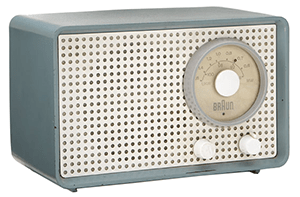

Dieter Rams

Dieter Rams (b. 1932) is a German industrial designer closely associated with the consumer products company Braun and the Functionalist school of industrial design. Rams studied architecture at the Werkkunstschule Wiesbaden as well as learning carpentry from 1943 to 1957. After working for the architect Otto Apel between 1953 and 1955 he joined the electronic devices manufacturer Braun where he became chief of design in 1961, a position he kept until 1995.

Rams once explained his design approach in the phrase ‘Weniger, aber besser’ which freely translates as ‘Less, but better.’ Rams and his staff designed many memorable products for Braun including the famous SK-4 record player and the high-quality ‘D’-series (D45, D46) of 35 mm film slide projectors. He is also known for designing the 606 Universal Shelving System by Vitsœ in 1960. Many of his designs — coffee makers, calculators, radios, audio/visual equipment, consumer appliances and office products — have found a permanent home at many museums over the world, including MoMA in New York. He continues to be highly regarded in design circles and currently has a major retrospective of his work on tour around the world.

read more »

Dystopia

A dystopia [dis-toh-pee-uh] is the idea of a society in a repressive and controlled state, often under the guise of being utopian, as characterized in books like ‘Brave New World’ and ‘Nineteen Eighty-Four.’

Dystopian societies feature different kinds of repressive social control systems, various forms of active and passive coercion. Ideas and works about dystopian societies often explore the concept of humans abusing technology and humans individually and collectively coping, or not being able to properly cope with technology that has progressed far more rapidly than humanity’s spiritual evolution. Dystopian societies are often imagined as police states, with unlimited power over the citizens.

read more »

Fahrenheit 451

Fahrenheit 451 is a 1953 dystopian novel by Ray Bradbury. The novel presents a future American society where reading is outlawed and firemen start fires to burn books. Written in the early years of the Cold War, the novel is a critique of what Bradbury saw as issues in American society of the era. In 1947, Bradbury wrote a short story titled ‘Bright Phoenix’ (later revised for publication in a 1963 issue of ‘The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction’). Bradbury expanded the basic premise of “Bright Phoenix” into ‘The Fireman,’ a novella published in a 1951 issue of ‘Galaxy Science Fiction.’ First published in 1953 by Ballantine Books, Fahrenheit 451 is twice as long as ‘The Fireman.’ A few months later, the novel was serialized in the March, April, and May 1954 issues of Playboy. Bradbury wrote the entire novel on a pay typewriter in the basement of UCLA’s Powell Library.

The novel has been the subject of various interpretations, primarily focusing on the historical role of book burning in suppressing dissenting ideas. Bradbury has stated that the novel is not about censorship, but a story about how television destroys interest in reading literature, which leads to a perception of knowledge as being composed of factoids, partial information devoid of context.

read more »