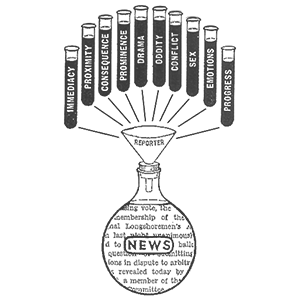

News values, or ‘news criteria,’ determine how much prominence a news story is given by a media outlet, and the attention it garners from its audience. These values are not universal and can vary widely between different cultures. In Western practice, decisions on the selection and prioritization of news are ostensibly made by editors on the basis of their experience and intuition.

However, a seminal analysis by Norwegian sociologists Johan Galtung and Mari Ruge in the ‘Journal of Peace Research’ in 1965 showed that several factors are common, such as familiarity (stories that ‘hit close to home’), negativity (‘if it bleeds, it leads’), and Unexpectedness (‘don’t report on fire in a furnace’). Basing his judgement on many years as a newspaper journalist Tim Hetherington has said that ‘anything which threatens people’s peace, prosperity, and well being is news and likely to make headlines.’ Continue reading

News Values

Great Disappointment

The Great Disappointment was the reaction that followed Baptist preacher William Miller’s proclamations that Jesus Christ would return to the earth in 1844. Many Millerites had given away all of their possessions and were left bereft when the prophecy proved false. Despite this, the movement wasn’t entirely disbanded, and eventually developed into several other denominations of Christianity, notably the Seventh Day Adventists.

The event is viewed by some scholars as indicative of ‘cognitive dissonance’ (discomfort from holding conflicting views) and ‘true-believer syndrome’ (maintaining a belief in the face of evidence to the contrary). The theory was proposed by social psychologist Leon Festinger to describe the formation of new beliefs and increased proselytizing in order to reduce the tension, or dissonance, that results from failed prophecies. His theory was that believers experienced emotional strain following the failure of Jesus’ reappearance in 1844, which led to a variety of new explanations, some of which outlived the disappointment. Continue reading

Dysrationalia

Dysrationalia [dis-rash-uh-ney-lee-uh] is defined as the inability to think and behave rationally despite adequate intelligence. Dysrationalia can be a resource to explain why smart people fall for Ponzi schemes and other fraudulent encounters. A survey given to a Canadian Mensa club (which grants membership solely based on high IQ scores) on the topic of paranormal belief found that 44% of the members believed in astrology.

There are many examples of people who are famous because of their intelligence, but often display irrational behavior. Martin Heidegger, a renowned philosopher, was also a Nazi apologist and used the most fallacious arguments to justify his beliefs. William Crookes, a famous scientist who discovered the element thallium and a Fellow of the Royal Society, was continually duped by spiritual ‘mediums’ yet never gave up his spiritualist beliefs. Continue reading

Political Correctness

Political correctness (PC) means using words or behavior which will not offend any group of people. The term arose in the 1970s as a way of encouraging the replacement of bygone phrases such as ‘colored.’ By the 1990s, it had taken on pejorative and mocking overtones, and was described as symptomatic of excessive liberalism and the ‘nanny state.’ The phrase was widely used in the debate about the 1987 book ‘The Closing of the American Mind’ by philosopher Allan Bloom, and gained further currency in response to social commentator Roger Kimball’s ‘Tenured Radicals’ (1990).

Conservative author Dinesh D’Souza’s ‘Illiberal Education’ duology of books (1991, 1992) condemned what he saw as liberal efforts to advance victimization, multiculturalism through language, and affirmative action. Advocates of political correctness, however, argue that libertarians made an issue of the term in order to divert attention from more substantive matters of discrimination and as part of a broader culture war against liberalism. They have also said that the right wing has it own forms of political correctness. Continue reading

Jugaad

Jugaad [joo-gard] is a colloquial Hindi and Punjabi word that can mean an innovative fix or a simple work-around, used for solutions that bend rules, or a resource that can be used as such, or a person who can solve a complicated issue. It is used as much to describe enterprising street mechanics as for political fixers. This meaning is often used to signify creativity to make existing things work or to create new things with meagre resources.

Jugaad is similar to the Western concepts of a ‘hack’ or ‘kludge,’ or to bodge or (‘British English’), but can be thought of more as a survival tactic than a mere workaround. But all such concepts express a need to do what needs to be done, without regard to what is conventionally supposed to be possible.

Whispering Gallery

A whispering gallery is a circular room in which whispers can be heard clearly across great distances. The sound is carried by waves, known as ‘whispering-gallery waves,’ that travel around the circumference clinging to the walls, an effect that was discovered in the whispering gallery of St Paul’s Cathedral in London. Other historical examples are the Gol Gumbaz mausoleum in India and the Echo Wall of the Temple of Heaven in Beijing.

The gallery may also be in the form of an ellipse or ellipsoid, with an accessible point at each focus. In this case, when a visitor stands at one focus and whispers, the line of sound emanating from this focus reflects directly to the focus at the other end of the gallery, where the whispers may be heard. In a similar way, two large concave parabolic dishes, serving as acoustic mirrors, may be erected facing each other in a room or outdoors to serve as a whispering gallery, a common feature of science museums. Egg-shaped galleries, such as the Golghar Granary in India, and irregularly shaped smooth-walled galleries in the form of caves, such as the Ear of Dionysius in Syracuse, also exist.

Jailhouse Lawyer

Jailhouse lawyer is a colloquial term in North American English to refer to an inmate in a jail or other prison who, though usually never having practiced law nor having any formal legal training, informally assists other inmates in legal matters relating to their sentence (e.g. appeal of their sentence, pardons, stays of execution, etc.) or to their conditions in prison. Sometimes, he or she also assists other inmates in civil matters of a legal nature. The term can also refer to a prison inmate who is representing themselves in legal matters relating to their sentence.

The important role that jailhouse lawyers play in the criminal justice system has been recognized by the US Supreme Court, which has held that jailhouse lawyers must be permitted to assist illiterate inmates in filing petitions for postconviction relief unless the state provides some reasonable alternative. Many states have ‘Jailhouse Lawyer Statutes,’ some of which exempt inmates acting as lawyers from the licensing requirements imposed on other attorneys when they are helping indigent inmates with legal matters. Cases brought by inmates have also called attention to the need for jailhouse lawyers to have access to law libraries.

Once Upon a Time

‘Once upon a time‘ is a stock phrase used to introduce a narrative of past events, typically in fairy tales and folktales. It has been used in some form since at least 1380 in storytelling in the English language and has opened many oral narratives since 1600. These stories often then end with ‘and they all lived happily ever after,’ or, originally, ‘happily until their deaths.’

The phrase is particularly common in fairy tales for younger children, where it is almost always the opening line of a tale. It was commonly used in the original translations of the stories of Charles Perrault as a translation for the French ‘il était une fois,’ of Hans Christian Andersen as a translation for the Danish ‘der var engang,’ (literally ‘there was once’), the Brothers Grimm as a translation for the German ‘es war einmal’ (literally ‘it was once’). An alternative German fairy tale opening translates to: ‘Back in the days when it was still of help to wish for a thing…’

ChromaDepth

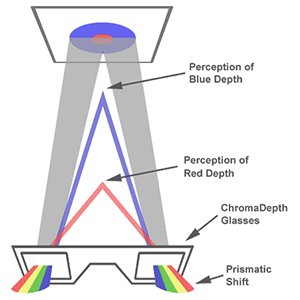

Chromadepth is a patented system from the company Chromatek (a subsidiary of American Paper Optics since 2002) that produces a stereoscopic effect based upon differences in the diffraction of color through a special prism-like holographic film. Chromadepth glasses purposely exacerbate chromatic aberration (the failure of a lens to focus all colors to the same convergence point) and give the illusion of colors taking up different positions in space, with red being in front, and blue being in back.

The effect works particularly well with the sky, sea or grass as a background, and redder objects in the foreground. From front to back the scheme follows the visible light spectrum, from red to orange, yellow, green and blue. This means any color is associated in a fixed fashion with a certain depth when viewing. As a result, ChromaDepth works best with artificially produced or enhanced pictures, since the color indicates the depth.

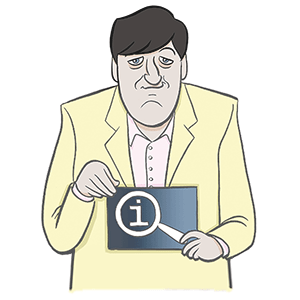

Quite Interesting

QI (‘Quite Interesting’) is a British television quiz show hosted by comedian Stephen Fry. There are four contestants in each show, of whom one is always stand-up comic Alan Davies. Most of the questions are extremely obscure, making it unlikely that the correct answer will be given. To compensate, points are awarded not only for right answers, but also for interesting ones, regardless of whether they are right or even relate to the original question.

QI has stated it follows a philosophy: everything in the world, even that which appears to be the most boring, is ‘quite interesting’ if looked at in the right way. Continue reading

Nudge Theory

Nudge theory is a concept in behavioral economics which argues that positive reinforcement and indirect suggestions promoting non-forced compliance can influence the motives, incentives, and decision making of groups and individuals, at least as effectively – if not more effectively – than direct instruction, legislation, or enforcement. The theory came to prominence with a 2008 book, ‘Nudge: Improving Decisions About Health, Wealth, and Happiness’ by behavioral economists Richard Thaler and Cass Sunstein.

They defined a ‘nudge’ as: ‘any aspect of the choice architecture that alters people’s behavior in a predictable way without forbidding any options or significantly changing their economic incentives. To count as a mere nudge, the intervention must be easy and cheap to avoid. Nudges are not mandates. Putting fruit at eye level counts as a nudge. Banning junk food does not.’ One of nudges’ most frequently cited examples is the etching of the image of a housefly into the men’s room urinals at Amsterdam’s Schiphol Airport, which is intended to ‘improve the aim.’

Pump and Dump

Pump and dump is a form of microcap stock fraud that involves artificially inflating the price of an owned stock through false and misleading positive statements, in order to sell the cheaply purchased stock at a higher price. Once the operators of the scheme ‘dump’ sell their overvalued shares, the price falls and investors lose their money. Stocks that are the subject of pump and dump schemes are sometimes called ‘chop stocks.’

While fraudsters in the past relied on cold calls made from ‘boiler rooms’ (outbound call centers selling questionable investments), the Internet now offers a cheaper and easier way of reaching large numbers of potential investors. Often the stock promoter will claim to have ‘inside’ information about impending news. They may also post messages in chat rooms or stock message boards urging readers to buy the stock quickly. Fraudsters frequently use this ploy with small, thinly traded companies—known as ‘penny stocks’ because it is easier to manipulate a stock when there is little or no independent information available about the company. Continue reading