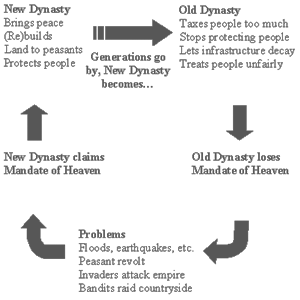

Social cycle theories are among the earliest social theories in sociology. Unlike the theory of social evolutionism, which views the evolution of society and human history as progressing in some new, unique direction(s), sociological cycle theory argues that events and stages of society and history are generally repeating themselves in cycles. Such a theory does not necessarily imply that there cannot be any social progress. In the early theory of ancient Chinese historian Sima Qian and the more recent theories of long-term (‘secular’) political-demographic cycles as well as in the Varnic theory of 20th century Indian philosopher P.R. Sarkar an explicit accounting is made of social progress.

The interpretation of history as repeating cycles of Dark and Golden Ages was a common belief among ancient cultures. The more limited cyclical view of history defined as repeating cycles of events was put forward in the academic world in the 19th century in historiosophy (a branch of historiography) and is a concept that falls under the category of sociology. However, Polybius, Ibn Khaldun, and Giambattista Vico can be seen as precursors of this analysis. The Saeculum (a length of time roughly equal to the potential lifetime of a person or the equivalent of the complete renewal of a human population) was identified in Roman times.

read more »

Social Cycle Theory

Devolution

Devolution [dev-uh-loo-shuh] is the notion that a species can change into a more ‘primitive’ form over time. Devolution presumes that there is a preferred hierarchy of structure and function, and that evolution must mean ‘progress’ to ‘more advanced’ organisms. This may include the idea that some modern species that have lost functions or complexity accordingly must be degenerate forms of their ancestors.

However, according to the definition of evolution, and particularly of the modern evolutionary synthesis in which natural selection leads to evolutionary adaptation, phenomena represented as instances of devolution are in every sense evolutionary. The idea of devolution is based at least partly on the presumption that ‘evolution’ requires some sort of purposeful direction towards ‘increasing complexity.’ Modern evolutionary theory poses no such presumption and the concept of evolutionary change is independent of either any increase in complexity of organisms sharing a gene pool, or any decrease, such as in vestigiality or in loss of genes.

read more »

Human Vestigiality

In the context of human evolution, human vestigiality [ve-stij-ee-al-i-tee] involves those characters (such as organs or behaviors) occurring in the human species that are considered vestigial—in other words having lost all or most of their original function through evolution. Although structures usually called ‘vestigial’ often appear functionless, a vestigial structure may retain lesser functions or develop minor new ones.

In some cases, structures once identified as vestigial simply had an unrecognized function. The examples of human vestigiality are numerous, including the anatomical (such as the human appendix, tailbone, wisdom teeth, and inside corner of the eye), the behavioral (goose bumps and infant grasp reflex), sensory (decreased olfaction), and molecular (junk DNA). Many human characteristics are also vestigial in other primates and related animals.

read more »

James Randi

James Randi (b. 1928) is a Canadian-American stage magician and scientific skeptic best known as a challenger of paranormal claims and pseudoscience. Randi is the founder of the James Randi Educational Foundation (JREF). Randi began his career as a magician, as The Amazing Randi, but after retiring at age 60, he began investigating paranormal, occult, and supernatural claims, which he collectively calls ‘woo-woo.’ He has written about the paranormal, skepticism, and the history of magic.

JREF sponsors The One Million Dollar Paranormal Challenge offering a prize of US$1,000,000 to anyone who can demonstrate evidence of any paranormal, supernatural or occult power or event under test conditions agreed to by both parties. Although often referred to as a ‘debunker,’ Randi dislikes the term’s connotations and prefers to describe himself as an ‘investigator.’ He has written about the paranormal, skepticism, and the history of magic. He was a frequent guest on ‘The Tonight Show Starring Johnny Carson’ and was occasionally featured on the television program ‘Penn & Teller: Bullshit!’

read more »

Free-radical Theory of Aging

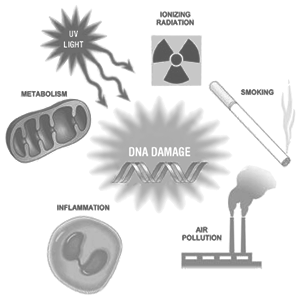

The free radical theory of aging states that organisms age because cells accumulate free radical damage over time. A free radical is a molecule with an unpaired electron. The molecule is reactive and seeks another electron to pair. This initiates an uncontrolled chain reaction that can damage the natural function of the living cell, causing various diseases. While a few free radicals such as melanin are not chemically reactive, most biologically-relevant free radicals are highly reactive.

For most biological structures, free radical damage is closely associated with oxidative damage. Antioxidants are reducing agents, they limit oxidative damage to biological structures by donating an electron to free radicals. Biogerontologist Denham Harman first proposed the free radical theory of aging in the 1950s, and in the 1970s extended the idea to implicate mitochondrial production of reactive oxygen species.

read more »

Negligible Senescence

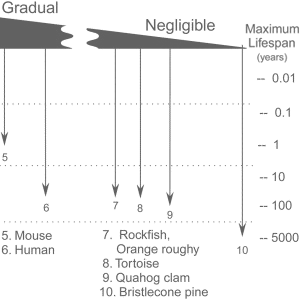

Negligible [neg-li-juh-buhl] senescence [si-nes-sens] refers to the lack of symptoms of aging in a few select animals. More specifically, negligibly senescent animals do not have measurable reductions in their reproductive capability with age, or measurable functional decline with age.

Death rates in negligibly senescent animals do not increase with age as they do in senescent organisms. Some fish, such as some varieties of sturgeon and rockfish, and some tortoises and turtles are thought to be negligibly senescent.

read more »

P versus NP

P versus NP is the name of a question that many mathematicians, scientists, and computer programmers want to answer. P and NP are two groups of mathematical problems. P problems are considered ‘easy’ for computers to solve. NP problems are easy only for a computer to check.

For example, if you have an NP problem, and someone says ‘The answer to your problem is 12345,’ a computer can quickly figure out if the answer is right or wrong, but it may take a very long time for the computer to come up with ‘12345’ on its own. All P problems are NP problems, because it is easy to check that a solution is correct by solving the problem and comparing the two solutions. However, people want to know about the opposite: Are there any NP problems that are not P problems, or are all NP problems just P problems?

read more »

Markov Chain

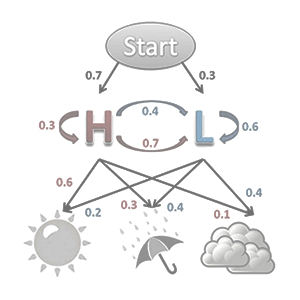

In mathematics, a Markov [mahr-kahv] chain, named after Russian mathematician Andrey Markov (1856 – 1922), is a discrete (finite or countable) random process with the Markov property (the memoryless property of a stochastic [random] process). A discrete random process means a system which can be in various states. The system also changes randomly in discrete steps. It can be helpful to think of the system as evolving through discrete steps in time, although strictly speaking the ‘step’ may have nothing to do with time.

A stochastic process has the Markov property if the conditional probability distribution of future states of the process depends only upon the present state, not on the sequence of events that preceded it. (Given two jointly distributed random variables X and Y, the conditional probability distribution of Y given X is the probability distribution of Y when X is known to be a particular value.) The term ‘Markov assumption’ is used to describe a model where the Markov property is assumed to hold, such as a hidden Markov model (in which the system being modeled is assumed to be a Markov process with unobserved [hidden] states).

read more »

Stochastic Process

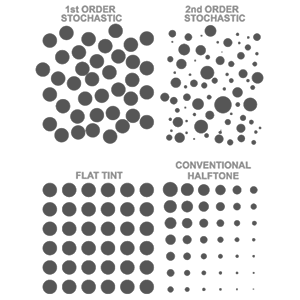

In the mathematics of probability, a stochastic [stuh-kas-tik] process is a random function, such as stock market and exchange rate fluctuations; signals such as speech, audio, and video; medical data such as a patient’s EKG, EEG, blood pressure, or temperature; and random movement such as Brownian motion (random moving of particles suspended in a fluid) or random walks (random, computer generated paths).

Other examples of random fields include static images, random topographies (landscapes), or composition variations of an inhomogeneous material. The stochastic process is the probabilistic counterpart to deterministic systems (in which no randomness is involved in the development of future states of the system). Instead of describing a process which can only evolve in one way, in a stochastic or random process there is some indeterminacy: even if the initial condition (or starting point) is known, there are several (often infinitely many) directions in which the process may evolve.

Mary Roach

Mary Roach is an American author, specializing in popular science. She currently resides in Oakland, California. To date, she has published four books: ‘Stiff: The Curious Lives of Human Cadavers’ (2003), ‘Spook: Science Tackles the Afterlife’ (2005), ‘Bonk: The Curious Coupling of Science and Sex’ (2008) and ‘Packing for Mars: The Curious Science of Life in the Void’ (2010). Roach was raised in Etna, New Hampshire.

She received a bachelor’s degree in psychology from Wesleyan University in 1981. After college, Roach moved to San Francisco and spent a few years working as a freelance copy editor. She worked as a columnist, and also worked in public relations for a brief time. Her writing career began while working part-time at the San Francisco Zoological Society, producing press releases on topics such as elephant wart surgery.

read more »

Antioxidant

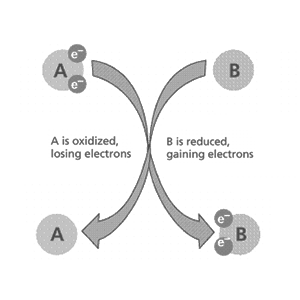

An antioxidant [an-tee-ok-si-duhnt] is a molecule that can slow or stop the oxidation, or loss of electrons, of other molecules. Oxidation reactions are necessary for many bodily functions but can produce free radicals (molecules with an unpaired electron). In turn, these radicals can start chain reactions. When the chain reaction occurs in a cell, it can cause damage or death to the cell. Antioxidants terminate these chain reactions by removing free radical intermediates. They do this by being oxidized themselves (donating an electron to the free radical).

Vitamins and enzymes can have antioxidant properties that neutralize the damaging effects of free radicals. Although oxidation reactions are crucial for life, they can also be damaging; plants and animals maintain complex systems of multiple types of antioxidants. Insufficient levels of antioxidants, or inhibition of the antioxidant enzymes, cause oxidative stress and may damage or kill cells. As oxidative stress appears to be an important part of many human diseases, the use of antioxidants in pharmacology is intensively studied, particularly as treatments for stroke and neurodegenerative diseases. Moreover, oxidative stress is both the cause and the consequence of disease.

read more »

Oxidation

Oxidation [ok-si-dey-shuhn] is any chemical reaction that involves a loss of electrons. For example, when iron reacts with oxygen it forms a chemical called rust: the iron is oxidized (loses electrons) and the oxygen is reduced (gains electrons).

A reduction reaction always comes together with its opposite, the oxidation reaction, and together are called ‘redox’ (reduction and oxidation). Although oxidation reactions are commonly associated with the formation of oxides from oxygen molecules, these are only specific examples of a more general concept of reactions involving electron transfer.

read more »