Article spinning is a search engine optimization technique by which blog or website owners post a unique version of relevant content on their sites by rewriting and replacing elements to provide a slightly different perspective on the topic. Many article marketers believe that article spinning helps avoid the feared penalties in the Search Engine Results pages (SERP) for using duplicate content. If the original articles are plagiarized from other websites or if the original article was used without the copyright owner’s permission, such copyright infringements may result in the writer facing a legal challenge, while writers producing multiple versions of their own original writing need not worry about such things.

Website owners may pay writers to perform spinning manually, rewriting all or parts of articles. Writers also spin their own articles, manually or automatically, allowing them to sell the same articles with slight variations to a number of clients or to use the article for multiple purposes (e.g. content and marketing). There are also a number of software applications which will automatically replace words or phrases in articles.

Article Spinning

Spamdexing

In computing, spamdexing (also known as search spam or Search Engine Poisoning) is the deliberate manipulation of search engine indexes. The earliest known reference to the term is by Eric Convey in 1996 in an article, ‘Porn sneaks way back on Web,’ for ‘The Boston Herald.’ It involves a number of methods, such as repeating unrelated phrases, to manipulate the relevance or prominence of resources indexed in a manner inconsistent with the purpose of the indexing system.

Common spamdexing techniques can be classified into two broad classes: content spam (or term spam) and link spam. Content spam methods include keyword stuffing, hidden or invisible text, meta-tag stuffing, doorway pages, scraper sites, and article spinning. Link spamming methods include link farms, hidden links, Sybil attacks, spam blogs, page hijacking, buying lapsed domains (cybersquatting), and cookie stuffing.

read more »

Brandjacking

Brandjacking is an activity whereby someone acquires or otherwise assumes the online identity of another entity for the purposes of acquiring that person’s or business’s brand equity. The term combines the notions of ‘branding’ and ‘hijacking’, and has been used since at least 2007 when it appeared in a Business Week article. The tactic is often associated with use of individual and corporate identities on social media or Web 2.0 sites.

While similar to cybersquatting, identity theft, and phishing, brandjacking is usually particular to a politician, celebrity or business and more indirect in its nature. A brandjacker may attempt to use the reputation of its target for selfish reasons or seek to damage the reputation of its target for malicious or for political reasons. These reasons may not be directly financial, but the effects on the original brand-holder may often include financial loss – for example, negative publicity may result in the termination of a celebrity’s sponsorship deal, or, for a corporation, potentially lead to lost sales or a reduced share price.

Cybersquatting

Cybersquatting (also known as domain squatting) is registering, trafficking in, or using a domain name with bad faith intent to profit from the goodwill of a trademark belonging to someone else. Some cybersquatter offer to sell the domain to the person or company who owns a trademark at an inflated price.

Some put up derogatory remarks about the person or company the domain is meant to represent to encourage the subject to buy the domain from them. Others post paid links via Google and other advertising networks. The term is derived from ‘squatting,’ which is the act of occupying an abandoned or unoccupied space or building that the squatter does not own, rent or otherwise have permission to use.

read more »

Google Bomb

The terms Google bomb and Googlewashing refer to practices, such as creating large numbers of links, that cause a web page to have a high ranking for searches on unrelated or off topic keyword phrases, often for comical or satirical purposes. In contrast, search engine optimization is the practice of improving the search engine listings of web pages for relevant search terms.

Google bombs date back as far as 1999, when a search for ‘more evil than Satan himself’ resulted in the Microsoft homepage as the top result. Some of the most famous Google bombs are also expressions of political opinions (e.g. ‘liar’ leading to Tony Blair or ‘miserable failure’ leading to the White House’s biography of George W. Bush).

read more »

Typosquatting

Typosquatting (URL hijacking), is a form of cybersquatting, and possibly brandjacking which relies on mistakes such as typographical errors made by Internet users when inputting a website address into a web browser. Should a user accidentally enter an incorrect website address, they may be led to an alternative website owned by a cybersquatter. Once in the typosquatter’s site, the user may also be tricked into thinking that they are in fact in the real site; through the use of copied or similar logos, website layouts or content.

In 2006, controversial evangelist Jerry Falwell failed to get the U.S. Supreme Court to review a decision allowing Christopher Lamparello to use ‘www.fallwell.com.’ Relying on a plausible misspelling of Falwell’s name, Lamparello’s gripe site presents misdirected visitors with scriptural references that counter the fundamentalist preacher’s scathing rebukes against homosexuality. In Lamparello v. Falwell, the high court let stand a 2005 lower court finding that ‘the use of a mark in a domain name for a gripe site criticizing the markholder does not constitute cybersquatting.’

Mousetrapping

Mousetrapping is a technique used by websites (usually pornographic) to keep visitors from leaving their website, either by launching an endless series of pop-up ads—known colloquially as a ‘circle jerk’—or by re-launching their website in a window that cannot be closed. Many websites that do this also employ browser hijackers to reset the user’s default homepage. The Federal Trade Commission has brought suits against mousetrappers, charging that the practice is a deceptive and unfair competitive practice.

Typically, mousetrappers register URLs with misspelled names of celebrities (e.g. BrittnaySpears.com) or companies (WallStreetJournel.com). Once the viewer is at the site, a Javascript or a click induced by promises of free samples redirects the viewer to a URL and regular site of the mousetrapper’s client-advertiser, who pays him 10 to 25 cents for capturing and redirecting each potential customer. An FTC press release explaining states: ‘Schemes that capture consumers and hold them at sites against their will while exposing Internet users, including children, to solicitations for gambling, psychics, lotteries, and pornography must be stopped.’

No Poo

No poo (short for ‘no shampoo’) is a collective term for methods of washing hair without commercial shampoo. Methods for washing hair without shampoo include washing with dissolved baking soda, followed by an acidic rinse such as diluted apple cider vinegar. Also honey and various oils (such as coconut oil) can be used. The notion of non-shampooed hair being unhealthy is reinforced by the greasy feeling of the scalp after a day or two of not shampooing. However, using shampoo every day removes sebum, the oil produced by the scalp. This causes the sebaceous glands to produce oil at a higher rate to compensate for what is lost during shampooing.

A gradual reduction in shampoo use will cause the sebaceous glands to produce at a slower rate, resulting in less oil on the scalp. Shampoo typically contains chemical additives such as sulfates (e.g. sodium lauryl sulfate). These chemicals can irritate the skin of sensitive persons (or of anyone if not promptly rinsed). Some shampoos also include silicone derivatives (e.g. dimethicone), which coats the hair, protecting it and making it more manageable; however, it also prevents moisture from entering the hair, eventually drying it out. Dimethicone is a common ingredient in smoothing serums and detangling conditioners.

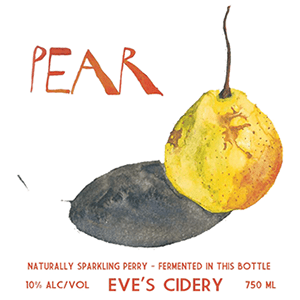

Perry

Perry is an alcoholic beverage made from fermented pears. Perry has been common for centuries in Britain, and in parts of south Wales; and France, especially Normandy and Anjou. In more recent years, commercial perry has also been referred to as ‘pear cider.’ Perry pears often have higher levels of sugar than cider apples, including unfermentable sugars such as sorbitol, which can give the finished drink a residual sweetness. They also have a very different tannin content to cider apples, with a predominance of astringent over bitter flavors. The presence of sorbitol can give perry a mild laxative effect, seen in the names of some perry pear varieties such as the ‘Lightning Pear’; reputed to go straight through ‘like lightning.’

As with apples specifically grown to make cider, special pear cultivars are used: in the UK the most commonly used variety of perry pear is the Blakeney Red. They produce fruit that is not of eating quality, but that produces superior perry. Like commercial pale lager and commercial cider, commercial perry is highly standardized, and today often contains large quantities of cereal adjuncts such as corn syrup or invert sugar. It is also generally of lower strength, and sweeter, than traditional perry, and is artificially carbonated to give a sparkling finish. However, unlike traditional perry it is a consistent product: the nature of perry pears means that it is very difficult to produce traditional perry in commercial quantities. Traditional perry was overwhelmingly a drink made on farms for home consumption, or to sell in small quantities either at the farm gate or to local inns.

Beer Glassware

Beer glassware comprises the drinking vessels made of glass designed or commonly used for drinking beer. Different styles of glassware exist for a number of reasons: national traditions; legislation regarding serving measures; practicalities of stacking, washing and avoiding breakage; promotion of commercial breweries; or they may be folk art, novelty items or used in drinking games.

They also may complement different styles of beer for a variety of reasons, including enhancing aromatic volatiles, showcasing the appearance, and/or having an effect on the beer head. Several kinds of beer glassware have a stem which serves to prevent the body heat of the drinker’s hand from warming the beer. Beer glasses include German steins, old English tankards, and Belgian novelty glassware.

read more »

Mello Yello

Mello Yello is a caffeinated, citrus-flavored soft drink produced and distributed by The Coca-Cola Company. It was introduced in 1979 to compete with PepsiCo’s Mountain Dew. There have been three flavored variants: Mello Yello Cherry was released in response to Mountain Dew Code Red, and the other two variants were Mello Yello Afterglow (peach-flavored) and Mello Yello Melon.

Mello Yello was featured in the 1990 NASCAR-based movie ‘Days Of Thunder,’ in which Tom Cruise’s character, Cole Trickle, drove a Mello Yello-sponsored car to victory in the Daytona 500, although the product name itself is never verbally mentioned in the movie. That livery went on to become a real NASCAR paint scheme the following year, when driver Kyle Petty drove with Mello Yello sponsorship in the Winston Cup Series.

Quartz Crisis

The Quartz Crisis is a term used in the watchmaking industry to refer to the economic upheavals caused by the advent of quartz watches in the 1970s and early 1980s, which largely replaced mechanical watches. It caused a decline of the Swiss watchmaking industry, which chose to remain focused on traditional mechanical watches, while the majority of world watch production shifted to Asian companies who embraced the new technology.

During World War II, Swiss neutrality permitted the watch industry to continue making consumer time keeping apparatus while the major nations of the world shifted timing apparatus production to timing devices for military ordnance. As a result, the Swiss watch Industry enjoyed a well-protected monopoly. The industry prospered in the absence of any real competition. Thus, prior to the 1970s, the Swiss watch industry had 50% of the world watch market.

read more »